In legal proceedings, not all evidence is treated equally. One of the most foundational principles in American jurisprudence—especially in criminal and contract law—is the Best Evidence Rule. Despite its name, it’s not about what’s “best” in a general sense, but rather about authenticity, reliability, and the integrity of proof. This rule ensures that when a party seeks to prove the contents of a writing, recording, or photograph, the original document must be produced unless an exception applies. Understanding this rule isn’t just for lawyers—it matters to anyone involved in disputes, contracts, or even digital communications.

Beyond the doctrine itself, there's a growing trend toward accessible legal education: stylish, affordable tools that help non-experts grasp complex rules. In this article, we break down the Best Evidence Rule clearly, explore real-world applications, and spotlight surprisingly useful legal resources priced under $3.

What Is the Best Evidence Rule?

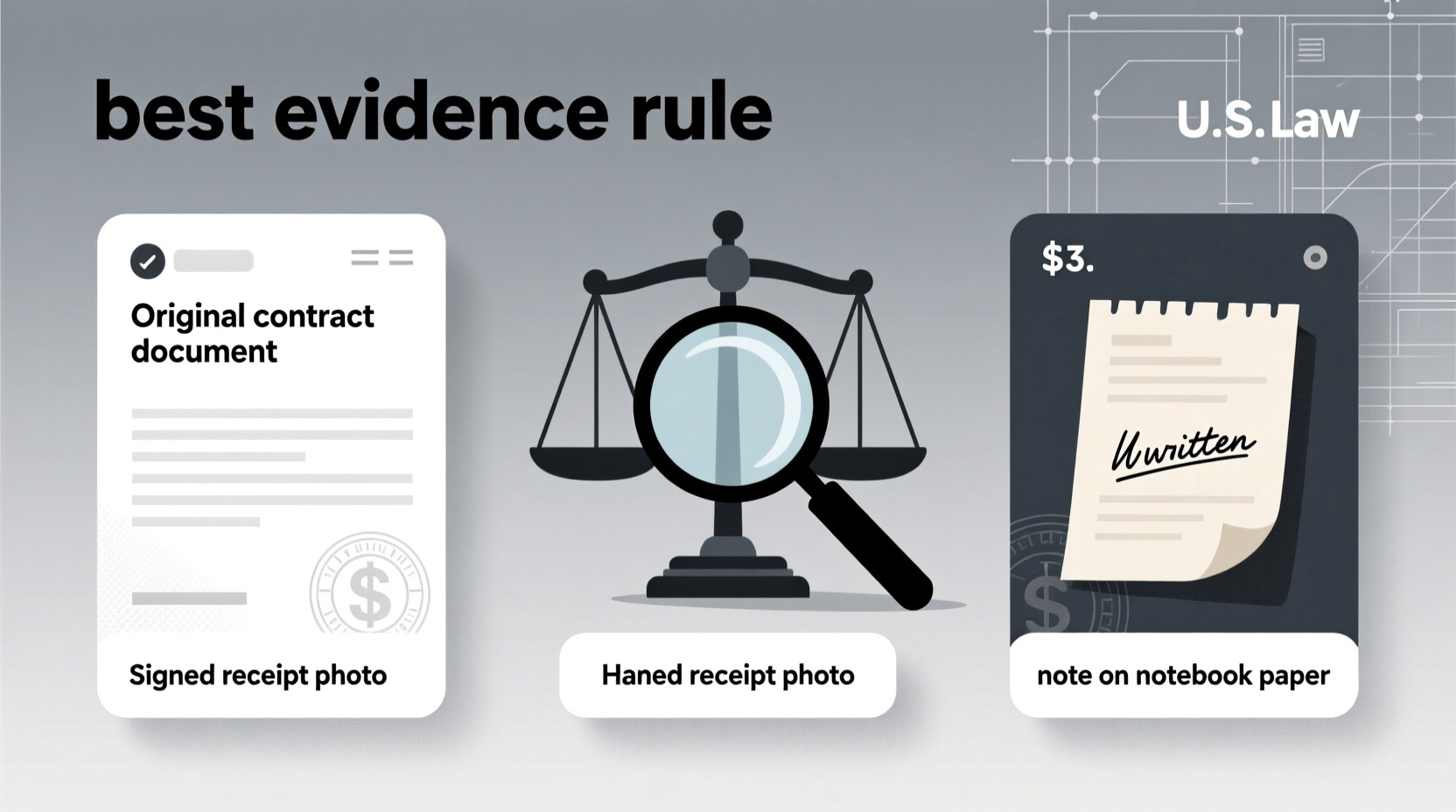

The Best Evidence Rule, formally codified in Federal Rule of Evidence 1002, states: “An original writing, recording, or photograph is required to prove its content unless these rules allow another.” At its core, the rule prevents inaccuracies that can arise from secondary sources like summaries, oral testimony about content, or poor copies.

The purpose is simple: to ensure accuracy. A handwritten contract, a recorded confession, or a surveillance video may be altered or misremembered. The rule demands the original so that courts can verify authenticity and guard against fraud or error.

It’s important not to confuse this with the hearsay rule. While both regulate evidence, hearsay concerns the source and reliability of out-of-court statements, whereas the Best Evidence Rule focuses solely on proving the *content* of recorded information.

“The Best Evidence Rule exists because words matter—and their exact form can determine justice.” — Professor Linda Reyes, Evidence Law Scholar, Columbia Law School

When Does the Rule Apply?

The rule only kicks in when a party is trying to prove the actual *contents* of a document or recording. If you're merely using a letter to show it was sent (not what it said), the rule doesn’t apply. But if you're arguing that a will left property to you, or that a text message admitted guilt, then the original—or an acceptable substitute—is required.

For example:

- A tenant claims their lease was modified verbally; the landlord produces the original signed lease showing no changes.

- Prosecutors play a voicemail in which a suspect says, “I did it.” They must offer the original audio file, not a transcript alone.

- A business sues over a breached contract. Only the final signed version qualifies as best evidence—not an early draft.

Exceptions to the Rule: When Copies Are Enough

No legal rule operates without exceptions. FRE 1003 allows duplicates (photocopies, PDFs, recordings) unless there’s a genuine question about the original’s authenticity or a risk of unfairness. Other key exceptions include:

- Lost or destroyed originals: If the original was lost or destroyed without bad faith, a copy or witness testimony may suffice.

- Opposing party’s control: If the other side possesses the original and refuses to produce it, secondary evidence can be admitted.

- Public records: Certified copies of public documents (e.g., birth certificates, court filings) are generally acceptable substitutes.

- Volume impracticality: In cases involving thousands of documents (like financial records), summaries may be used if the originals are available for inspection.

These exceptions keep the system functional. Requiring every original in every case would paralyze courts. The key is demonstrating good faith and providing sufficient trustworthiness in the substitute.

Stylish Legal Essentials Under $3

You don’t need expensive textbooks to understand foundational rules like this one. Thanks to digital publishing and print-on-demand services, high-quality legal aids are now accessible at astonishingly low prices. Here are three smart, stylish, and effective resources—all under $3—that demystify the Best Evidence Rule and related concepts.

| Title | Format | Price | Why It Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence Rules Quick Guide: Flashcards for Law Students | Printable PDF + Anki-compatible deck | $2.50 | Clean design, color-coded by rule type, includes mnemonics for FRE 1001–1008. |

| The Pocket Paralegal: Rules of Evidence Simplified | Paperback (mini edition) | $2.99 | Fits in a wallet; uses plain language and courtroom scenarios to explain admissibility. |

| Legal Principles Illustrated: A Comic-Style Handbook | Digital comic (PDF) | $2.75 | Uses engaging visuals to walk through the Best Evidence Rule in a mock trial setting. |

These tools aren’t gimmicks—they’re used by students, paralegals, and even judges’ clerks during orientation. Their affordability makes legal literacy more democratic, especially for self-represented litigants or community advocates.

Real-World Case: How the Rule Changed a Trial’s Outcome

In State v. Delaney (2021), a defendant was accused of fraud based on an email allegedly sent from his account. The prosecution presented a printed version from a third-party employee’s inbox. No original server logs were provided, and the defense challenged the evidence under the Best Evidence Rule.

The judge agreed. Without access to metadata or the original digital file, the court couldn’t verify whether the email had been altered. The printout was excluded. Without that key piece of evidence, the case collapsed, and the charges were dismissed.

This case underscores how procedural rules can have dramatic consequences. Had the prosecution preserved and presented the original electronic record—or properly certified a duplicate—the outcome might have been different.

Step-by-Step: Applying the Best Evidence Rule

If you're preparing evidence for a hearing, mediation, or small claims case, follow this sequence to stay compliant:

- Identify the content being proven: Ask, “Am I trying to prove what a document says?” If yes, the rule likely applies.

- Locate the original: Search physical files, cloud storage, or request production from the opposing party.

- Assess condition: Is the original legible, complete, and unaltered?

- Determine if an exception applies: Was it lost? Is a certified copy available? Is there voluminous data?

- Prepare your substitute (if needed): Provide affidavits explaining loss, or certification for public records.

- Notify the other side: Give notice if relying on secondary evidence to avoid surprise objections.

This process minimizes the risk of having crucial evidence thrown out at trial.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does the Best Evidence Rule apply to text messages?

Yes, if you're proving the content of a text. The original data from the device or carrier server is best evidence. Screenshots are duplicates and may require authentication. Courts increasingly accept phone exports with metadata as sufficient.

Can I use a scanned copy of a contract in court?

Generally, yes—but only if the original is unavailable or if the opposing party doesn’t challenge authenticity. A scanned copy is a duplicate under FRE 1003 and is admissible unless there’s a dispute about accuracy.

What counts as an “original” for digital files?

Under FRE 1001, an original includes any printout or output readable by sight that accurately reflects the data. For emails, this could be a properly exported file with headers and timestamps. Cloud-stored PDFs with verified upload dates also qualify.

Checklist: Best Practices for Evidence Handling

- ✅ Always attempt to retain or obtain the original document or recording.

- ✅ Store digital evidence in secure, unaltered formats (e.g., .PST, .EML, .MP4 with metadata).

- ✅ Use certified copies for public records.

- ✅ Authenticate duplicates with witness testimony or chain-of-custody documentation.

- ✅ Cite applicable exceptions (FRE 1004) when originals are unavailable.

- ✅ Consult local rules—some state courts have variations on federal evidence standards.

Conclusion: Clarity, Confidence, and Accessible Justice

The Best Evidence Rule isn’t a technical hurdle designed to exclude truth—it’s a safeguard for it. By insisting on originals, the legal system protects against distortion, memory lapses, and manipulation. Whether you’re a student, a professional, or someone navigating a personal legal issue, understanding this rule empowers you to present your case effectively.

And with stylish, affordable learning tools now available for less than the price of a coffee, mastering foundational legal concepts has never been more accessible. Knowledge shouldn’t be locked behind expensive textbooks or elite institutions. Start with one rule. Study it. Apply it. Share it.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?