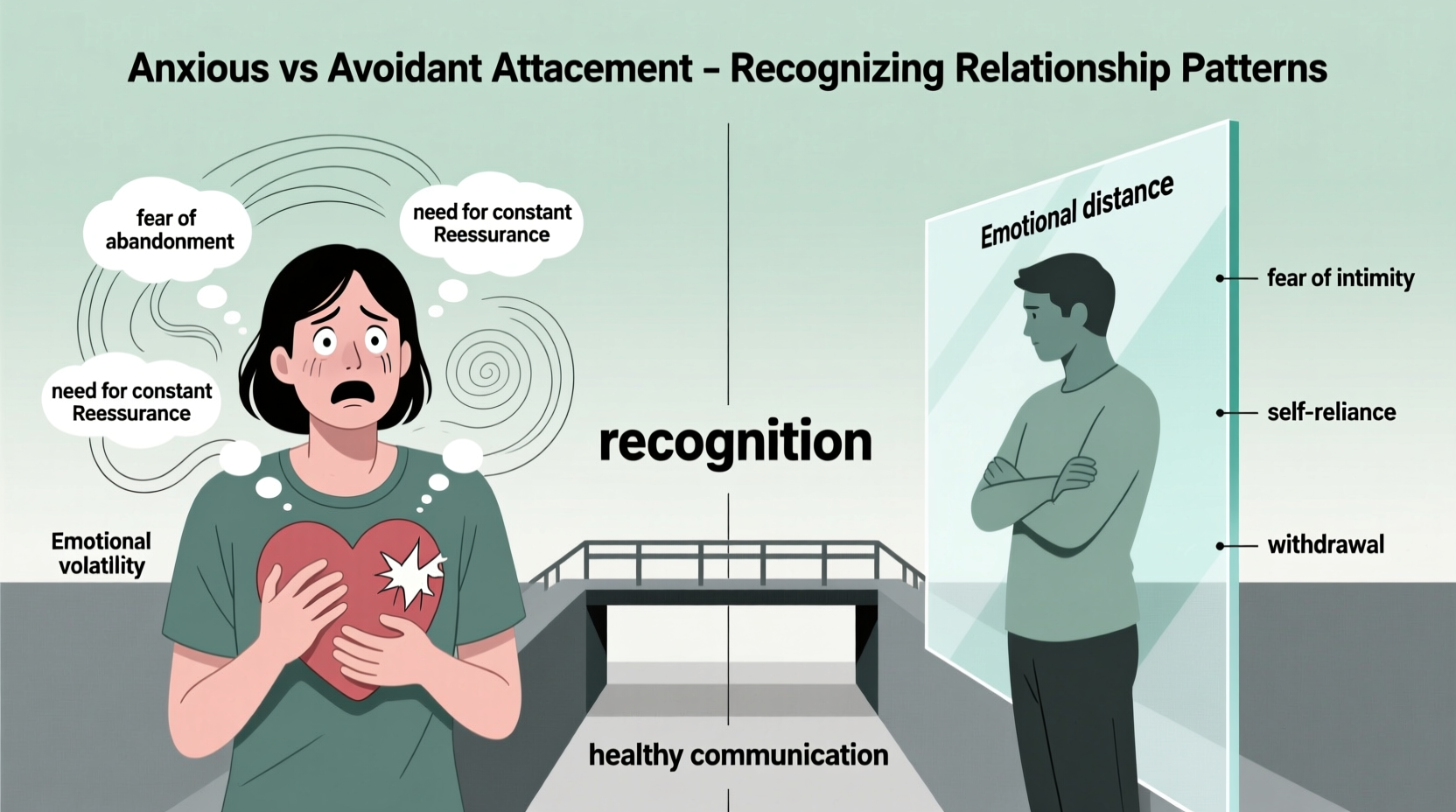

Relationships are complex, shaped not just by personality and circumstance but by deep emotional blueprints formed early in life. Among the most influential of these are attachment styles—internal frameworks that dictate how we connect with others, express needs, and respond to intimacy. Two of the most common insecure attachment patterns are anxious and avoidant attachment. When these two clash—often magnetically—they can create cycles of misunderstanding, frustration, and emotional exhaustion. Recognizing these dynamics is the first step toward breaking unhealthy patterns and cultivating more secure, fulfilling relationships.

Understanding Attachment Theory: The Foundation

Attachment theory, originally developed by psychologist John Bowlby and later expanded by Mary Ainsworth, explains how early interactions with caregivers shape our expectations in adult relationships. These early experiences form internal working models of self and others—essentially subconscious templates for how love works. There are four primary adult attachment styles:

- Secure: Comfortable with intimacy and independence; able to communicate needs clearly.

- Anxious (Preoccupied): Craves closeness but fears abandonment; often hyper-vigilant to relational cues.

- Avoidant (Dismissive): Values independence over intimacy; uncomfortable with emotional vulnerability.

- Fearful-Avoidant (Disorganized): A mix of anxious and avoidant traits; desires connection but fears getting hurt.

While secure attachment allows for balanced, trusting relationships, anxious and avoidant styles often lead to push-pull dynamics—especially when they interact. Understanding these patterns isn’t about labeling or blaming, but about gaining insight into behaviors that may feel automatic yet are deeply changeable.

Anxious Attachment: The Fear of Abandonment

An individual with an anxious attachment style typically grew up in an environment where caregiving was inconsistent—sometimes responsive, sometimes distant or dismissive. As a result, they learned that affection must be earned through attention-seeking or emotional intensity. In adulthood, this manifests as a heightened sensitivity to perceived rejection.

Common signs of anxious attachment include:

- Needing frequent reassurance (“Do you still love me?”)

- Overanalyzing texts, tone, or delays in response

- Feeling overwhelmed by jealousy or insecurity

- Tending to “pursue” during conflict instead of withdrawing

- Equating intense emotions with love

These behaviors stem not from neediness, but from a deep fear of being unlovable or abandoned. The anxious partner often mistakes anxiety for passion and interprets their partner’s calmness as indifference.

Avoidant Attachment: The Need for Emotional Distance

Avoidant attachment typically develops when caregivers were emotionally unavailable, dismissive of feelings, or prioritized self-reliance. Children in these environments learn to suppress emotional needs and equate dependence with weakness. As adults, they value autonomy above all and may see intimacy as a threat to independence.

Signs of avoidant attachment include:

- Keeping emotional walls even in long-term relationships

- Downplaying the importance of closeness (“I don’t need much from anyone”)

- Withdrawing during conflict or emotional discussions

- Valuing logic over emotion

- Feeling suffocated when a partner seeks more connection

The avoidant individual isn't necessarily cold-hearted—they may deeply care but lack the tools to express it. Their discomfort with vulnerability often leads them to pull away just as intimacy deepens, reinforcing their partner's fears.

“People with avoidant tendencies aren’t rejecting love—they’re protecting themselves from what they’ve learned love feels like: engulfment, loss of control, or emotional chaos.” — Dr. Amira Chen, Clinical Psychologist

The Anxious-Avoidant Trap: Why Opposites Attract (and Stay Stuck)

Paradoxically, anxious and avoidant individuals are often drawn to each other. The anxious person sees the avoidant as calm, stable, and self-sufficient—qualities they admire. The avoidant sees the anxious person as passionate, warm, and deeply invested—qualities that initially feel exciting. But over time, their differences create a feedback loop:

- The anxious partner seeks more closeness.

- The avoidant partner feels pressured and withdraws.

- The anxious partner perceives withdrawal as rejection and escalates pursuit.

- The avoidant partner feels smothered and distances further.

This cycle, known as the “pursuer-distancer dynamic,” can persist for years if unrecognized. Each person misinterprets the other’s behavior: the anxious one sees coldness where there is fear; the avoidant one sees neediness where there is longing.

| Behavior | Anxious Response | Avoidant Response |

|---|---|---|

| Partner is quiet after work | “Are they upset with me? Did I do something wrong?” | “I just need space to decompress. They should understand.” |

| Conflict arises | Wants to talk immediately; fears unresolved tension | Needs time alone; avoids discussion until emotions settle |

| Plans change last minute | Feels rejected; questions relationship stability | Sees it as practical; doesn’t attach emotional meaning |

| Expressions of love | Craves verbal affirmation and physical touch | Shows care through actions, not words; dislikes gushing |

Without awareness, both partners become trapped in roles: the pursuer and the distancer. The relationship becomes less about connection and more about managing each other’s triggers.

Breaking the Cycle: A Step-by-Step Guide to Healthier Patterns

Change begins with self-awareness and intentional action. Whether you identify as anxious, avoidant, or are in a relationship with someone who does, the following steps can help disrupt old patterns and foster security.

Step 1: Identify Your Attachment Style

Reflect honestly on your relational history. Do you panic when your partner doesn’t reply? Or do you feel relieved when they’re busy? Take validated assessments like the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) questionnaire to gain clarity.

Step 2: Name the Pattern Without Judgment

When tension arises, pause and label the dynamic: “This feels like my anxious side reacting,” or “I’m pulling away because I’m uncomfortable.” Naming reduces shame and increases agency.

Step 3: Regulate Before You Communicate

Reacting from emotional flooding rarely leads to resolution. Anxious types benefit from grounding techniques (breathing, journaling); avoidant types benefit from scheduling time to return to conversation rather than disappearing.

Step 4: Practice Secure Communication

Use “I” statements: “I feel anxious when we don’t talk for days—I’d appreciate a quick check-in.” Avoid blame: “You always shut down when I try to talk.”

Step 5: Build Tolerance for Discomfort

Anxious individuals must practice sitting with uncertainty without seeking instant reassurance. Avoidant individuals must practice staying present during emotional conversations, even briefly.

Step 6: Seek Feedback and Adjust

Ask your partner: “How do I typically react when stressed? What helps you feel safe?” Mutual curiosity builds empathy and trust.

Mini Case Study: Maya and Jordan’s Relationship Turnaround

Maya, 32, would text her boyfriend Jordan multiple times a day, growing anxious if he didn’t respond within an hour. Jordan, 34, prided himself on his independence and often left messages unanswered for hours, seeing them as interruptions. After a blow-up argument where Maya accused him of not caring and Jordan said she was “too much,” they sought couples counseling.

Through therapy, Maya recognized her pattern of equating responsiveness with love—a holdover from her childhood, where her mother was emotionally unpredictable. Jordan realized his discomfort with texting wasn’t about busyness, but fear of obligation. They agreed on a simple compromise: Jordan would send a brief “Got your message—talk tonight?” note when busy, and Maya committed to waiting at least three hours before following up unless urgent.

Over time, they introduced regular emotional check-ins and began interpreting each other’s behaviors more charitably. Maya learned that Jordan’s quietness wasn’t rejection; Jordan learned that Maya’s reach-outs weren’t manipulation. Their relationship didn’t become perfect—but it became safer, more honest, and deeply connected.

Checklist: Building a Secure Relationship Despite Insecure Tendencies

Use this actionable checklist to foster healthier dynamics:

- ☑ Reflect daily: Did I act from fear or choice today?

- ☑ Practice one small act of vulnerability this week (e.g., sharing a worry, asking for a hug).

- ☑ Notice when you’re falling into pursuer or distancer mode—and pause.

- ☑ Replace criticism with curiosity: “When you did X, I felt Y. Can you help me understand your perspective?”

- ☑ Schedule consistent quality time without distractions.

- ☑ Consider individual or couples therapy to explore deeper patterns.

- ☑ Celebrate progress, not perfection.

FAQ

Can an anxious and avoidant person have a successful relationship?

Yes—but only with awareness, effort, and mutual commitment to growth. Without intervention, the anxious-avoidant cycle tends to intensify. With intentional communication and emotional regulation skills, however, many such couples develop secure bonds over time.

Can you change your attachment style?

Absolutely. While early experiences shape attachment, adult relationships and therapeutic work can foster earned security. This doesn’t happen overnight, but through consistent experiences of reliability, empathy, and emotional honesty.

What if my partner refuses to acknowledge their attachment pattern?

You can’t force insight, but you can model it. Focus on your own responses: “I notice I get anxious when we don’t talk—so I’m working on giving space while also expressing my needs.” Often, one person’s growth inspires the other’s.

Conclusion: Toward Earned Security

Recognizing anxious and avoidant attachment patterns isn’t about assigning fault—it’s about reclaiming agency. Every reactive text, every silent retreat, every moment of misinterpretation is an opportunity to pause, reflect, and choose differently. The goal isn’t to eliminate anxiety or avoid vulnerability altogether, but to respond to them with wisdom rather than compulsion.

Healthy relationships aren’t built on perfect compatibility, but on the willingness to grow together. Whether you’re learning to soothe your own fears or sit with discomfort for the sake of connection, each step moves you closer to earned security—the kind of love that’s not instinctive, but intentional. And that kind of love lasts.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?