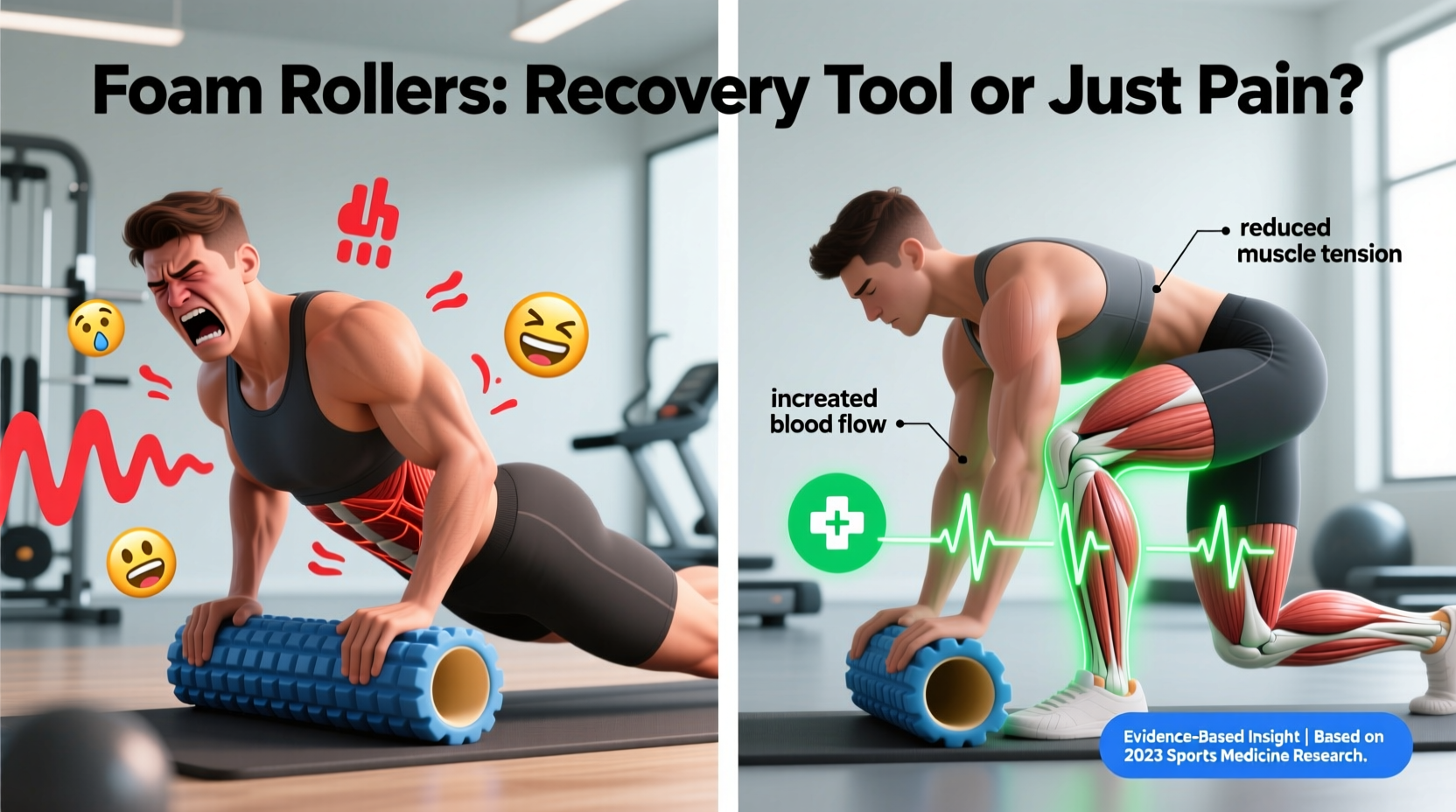

For years, fitness enthusiasts, athletes, and weekend warriors have debated whether foam rollers are essential tools for recovery or just instruments of self-inflicted torture. You’ve likely seen someone grimace while rolling their IT band on a hard cylinder, wondering: Is this really helping—or just masochism disguised as therapy? The truth lies somewhere in between. When used correctly, foam rollers can be powerful allies in muscle recovery. But misuse, overuse, or misunderstanding their purpose turns them into painful props with questionable returns.

The science is evolving, but current evidence supports strategic foam rolling as a legitimate method to reduce muscle soreness, improve range of motion, and support circulation after intense activity. However, it’s not magic—and it’s certainly not a one-size-fits-all solution. Understanding how and why it works (or doesn’t) separates effective recovery from pointless discomfort.

How Foam Rolling Works: The Science Behind the Squeeze

Foam rolling falls under the category of self-myofascial release (SMR), a technique designed to relieve tension in muscles and fascia—the connective tissue surrounding muscles, organs, and bones. When muscles are overused or injured, they can develop tight spots known as “trigger points” or “knots.” These areas restrict movement, contribute to discomfort, and may impair performance.

Applying pressure via a foam roller stimulates mechanoreceptors in the muscle and fascia, prompting a neurological response that can lead to temporary relaxation of the tissue. This process is believed to:

- Improve blood flow to fatigued muscles

- Reduce perceived muscle stiffness

- Enhance short-term flexibility

- Decrease delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS)

A 2015 study published in the Journal of Athletic Training found that participants who foam rolled after intense exercise reported significantly less muscle soreness over the next 72 hours compared to those who didn’t. Another meta-analysis in Frontiers in Physiology concluded that foam rolling produces small-to-moderate improvements in joint range of motion without compromising muscle strength—making it a safe pre- or post-workout option.

“Foam rolling isn’t about crushing pain—it’s about modulating tissue sensitivity and encouraging circulation. Done properly, it can be a valuable part of a recovery toolkit.” — Dr. Laura Chen, Sports Physiologist at Movement Health Institute

When Foam Rolling Helps—and When It Doesn’t

Not every ache or tightness responds well to foam rolling. Its effectiveness depends on timing, technique, and individual physiology. Below is a breakdown of common scenarios and whether foam rolling is likely beneficial.

| Situation | Recommended? | Why/Why Not |

|---|---|---|

| Post-workout muscle soreness (DOMS) | Yes | Reduces soreness and improves mobility within 24–72 hours post-exercise. |

| Tight hamstrings before stretching | Yes | Can enhance stretch effectiveness by reducing neural inhibition. |

| Acute injury (e.g., pulled muscle) | No | Pressure may worsen inflammation; rest and medical advice are better options. |

| Chronic lower back pain | Use Caution | Rolling the lower back directly can compress vertebrae; focus on glutes and hips instead. |

| Pre-workout activation | Limited Use | Brief rolling may help warm up tissue, but excessive time can fatigue muscles. |

Common Mistakes That Make Foam Rolling Painful

Many people abandon foam rolling because it feels too uncomfortable. More often than not, the pain stems from poor form or misconceptions about how it should feel. Here are the most frequent errors:

- Rolling too fast: Quick passes don’t allow tissues to respond. Slow, controlled movements yield better results.

- Holding your breath: Tension builds when you forget to breathe. Inhale deeply, exhale slowly as you roll through tight spots.

- Targeting the wrong areas: Rolling directly over bony prominences (like knees or elbows) causes pain without benefit.

- Spending too long on one spot: More than 30–60 seconds on a single area can irritate tissue rather than soothe it.

- Using excessive pressure: Especially with high-density rollers or vibrating models, too much force triggers protective muscle guarding.

The goal is not to endure pain, but to create a “good hurt”—a mild discomfort that eases within seconds. If you’re clenching your jaw or holding your breath, you're pushing too hard.

Step-by-Step Guide to Effective Foam Rolling

To get real benefits without unnecessary agony, follow this structured approach. Perform this routine 2–3 times per week, or after strenuous workouts.

- Choose the right roller: Beginners should start with a medium-density foam roller. Advanced users may use textured or vibrating rollers for deeper input.

- Warm up lightly: Do 5 minutes of walking or dynamic movement to increase blood flow before rolling.

- Target major muscle groups: Spend 30–60 seconds on each of the following:

- Quadriceps (front of thighs)

- Hamstrings (back of thighs)

- Calves

- Glutes and piriformis

- Upper back (avoid lower back)

- IT bands (outer thighs—go gently, as these are sensitive)

- Move slowly: Roll about one inch per second. Pause for 10–20 seconds on any tender spots, breathing steadily until tension releases slightly.

- Follow with stretching or movement: After rolling, perform dynamic stretches or light activity to reinforce improved mobility.

- Hydrate afterward: Drinking water helps flush metabolic waste and supports tissue recovery.

Mini Case Study: From Skeptic to Advocate

Mark, a 34-year-old recreational runner, avoided foam rolling for years, calling it “torture with no payoff.” After a half-marathon, he experienced severe DOMS and couldn’t walk comfortably for two days. A physical therapist suggested he try foam rolling with proper guidance. She taught him to slow down, focus on his breath, and avoid aggressive pressure.

He started rolling his quads, calves, and glutes for 10 minutes after runs, using a moderate-density roller. Within three weeks, he noticed faster recovery and reduced soreness. He still avoids the IT band—he says it’s “too much, even now”—but credits foam rolling with helping him stay consistent with training. “It’s not about beating up your body,” he says. “It’s about listening to it.”

Do’s and Don’ts of Foam Rolling

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Roll major muscle groups slowly and mindfully | Rush through sessions or multitask while rolling |

| Breathe deeply and relax into tight spots | Hold your breath or tense up during pressure |

| Use rolling to complement stretching and hydration | Expect instant fixes or rely solely on rolling for recovery |

| Start with softer rollers if new to SMR | Begin with aggressive tools like rumble rollers |

| Stop if you feel sharp or nerve-like pain | Push through pain that radiates or feels electric |

FAQ: Your Top Foam Rolling Questions Answered

Does foam rolling break up muscle knots?

Not exactly. While popular messaging suggests foam rolling “breaks up” adhesions, research shows fascia is too strong to be physically torn by body weight on a roller. Instead, the pressure likely changes the nervous system’s sensitivity to tension, making muscles feel looser. The effect is neurological more than structural.

Should I foam roll before or after my workout?

Both can work, but for different reasons. Pre-workout rolling should be brief (5–10 minutes) and dynamic, aimed at warming up tissue. Post-workout rolling is more effective for reducing soreness and promoting recovery. Avoid long, intense sessions before lifting or sprinting, as they may temporarily reduce muscle power.

Is more pressure always better?

No. Excessive pressure activates the body’s protective mechanisms, causing muscles to tighten rather than release. High-density rollers and vibrating models can be effective—but only when used with control and awareness. More pressure isn’t better; appropriate pressure is.

Maximizing Recovery: Where Foam Rolling Fits In

Foam rolling is just one piece of the recovery puzzle. It works best when combined with other evidence-based strategies:

- Sleep: Aim for 7–9 hours nightly. Most tissue repair happens during deep sleep.

- Nutrition: Consume adequate protein and anti-inflammatory foods (like berries, leafy greens, and fatty fish).

- Hydration: Dehydrated muscles are stiffer and more prone to cramping.

- Movement: Light activity (walking, cycling) boosts circulation better than complete rest.

- Active recovery: Incorporate yoga, swimming, or mobility drills on off days.

Think of foam rolling as a tune-up—not a cure-all. It won’t replace rest or fix biomechanical imbalances, but it can make daily movement feel smoother and speed up the return to peak performance.

Conclusion: Pain Isn’t the Goal—Progress Is

Foam rollers aren’t inherently useful or useless. Their value depends entirely on how they’re used. When applied with patience, proper technique, and realistic expectations, they can meaningfully support muscle recovery and comfort. But when treated as instruments of punishment or quick fixes, they deliver little beyond soreness and frustration.

The key is shifting mindset: from chasing pain to seeking release. From grinding away at tight spots to working collaboratively with your body’s feedback. If foam rolling hurts more than helps, adjust your approach—try a softer roller, go slower, or consult a physical therapist.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?