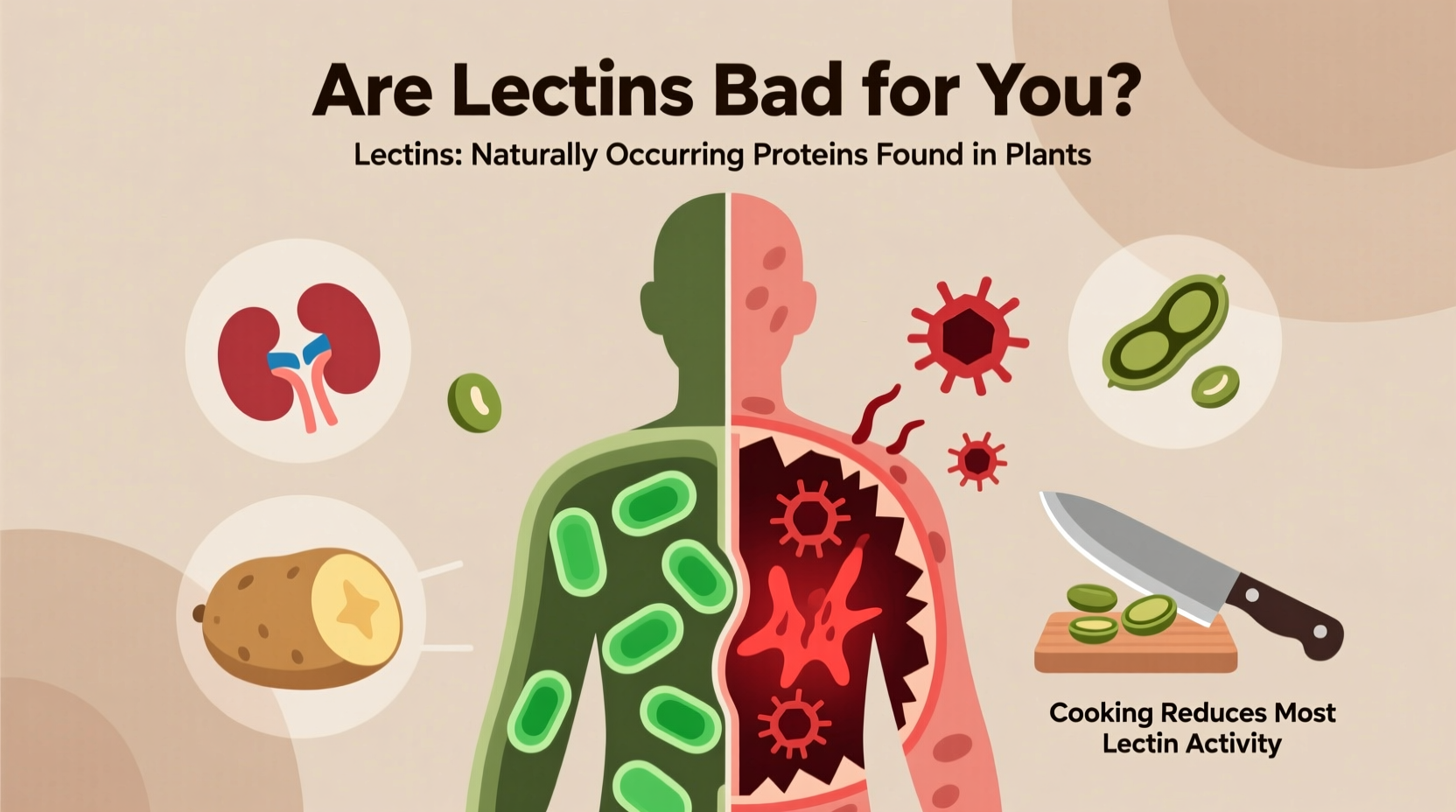

Lectins are a type of protein found in many plant-based foods, particularly legumes, whole grains, and nightshade vegetables. While they play a natural role in plant defense, there’s growing debate about whether they’re harmful to human health. Some diets, like the popular \"lectin-free\" approach, claim that eliminating these proteins can reduce inflammation, improve digestion, and even prevent chronic disease. But what does the science actually say? Understanding the role of lectins—and separating fact from dietary fad—is essential for making informed food choices.

What Are Lectins and Where Are They Found?

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins present in nearly all plants and animals, but they’re most concentrated in certain foods. Unlike enzymes or hormones, lectins aren’t broken down easily during digestion, which has led to concern about their bioavailability and impact on gut health.

Common dietary sources of lectins include:

- Legumes (e.g., beans, lentils, peanuts)

- Whole grains (e.g., wheat, rice, barley)

- Nightshade vegetables (e.g., tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants)

- Dairy products (especially A1 casein milk)

- Soy products

The most studied lectin is phytohaemagglutinin, found in raw red kidney beans. In high amounts, this compound can cause severe gastrointestinal distress. However, proper preparation methods—like soaking and boiling—significantly reduce its activity.

The Potential Health Concerns of Lectins

Critics of lectin-rich foods argue that these proteins can interfere with nutrient absorption, damage the gut lining, and trigger immune responses. The primary concerns include:

Gut Barrier Disruption

Lectins may bind to cells in the intestinal wall, potentially weakening tight junctions and contributing to “leaky gut.” This condition allows undigested food particles and bacteria to enter the bloodstream, possibly leading to systemic inflammation and autoimmune reactions.

Nutrient Interference

Some lectins bind to minerals like calcium, iron, and zinc, reducing their absorption. This effect is more relevant in populations relying heavily on unprocessed plant staples without diversified diets.

Inflammatory Response

Animal and in vitro studies suggest certain lectins can activate pro-inflammatory pathways. However, human evidence remains limited, and context—such as overall diet quality and gut microbiome health—plays a critical role.

“While isolated lectins can be problematic in lab settings, whole foods containing them often come with fiber, antioxidants, and polyphenols that mitigate potential harm.” — Dr. Sarah Nguyen, Registered Dietitian and Gut Health Researcher

Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risks?

Many lectin-containing foods are staples in some of the world’s healthiest diets, including the Mediterranean and Okinawan patterns. Beans, whole grains, and vegetables linked to longevity are also rich in lectins—yet populations consuming them regularly experience lower rates of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

This paradox suggests that preparation methods and dietary context matter more than lectin content alone. Cooking, fermenting, and sprouting can reduce lectin levels by up to 95%, making these foods safe and nutritious for most people.

| Food | Lectin Level (Raw) | Reduction Method | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Kidney Beans | Very High | Boiling (100°C for 10+ min) | ~98% reduction |

| Lentils | High | Soaking + Boiling | ~80% reduction |

| Wheat Germ | Moderate | Fermentation (sourdough) | ~70% reduction |

| Tomatoes | Low | Cooking/Processing | Minimal needed |

Who Might Need to Limit Lectin Intake?

For the general population, lectins in properly prepared foods pose little risk. However, certain individuals may benefit from reduced intake:

- People with autoimmune conditions: Some evidence suggests lectins may exacerbate symptoms in those with rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- Those with diagnosed gut permeability: Individuals with confirmed leaky gut or SIBO may find symptom relief on a lower-lectin diet under medical supervision.

- Individuals sensitive to nightshades: While not directly tied to lectins, some report joint pain relief when avoiding tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants.

Mini Case Study: Managing IBS Symptoms

A 42-year-old woman with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) struggled with bloating and abdominal pain despite following a high-fiber, plant-rich diet. After working with a dietitian, she discovered that raw salads with raw tomatoes and lentils triggered her symptoms. By switching to cooked vegetables, well-boiled lentils, and fermented sourdough bread, her digestive discomfort decreased significantly. This wasn’t due to eliminating lectins entirely, but rather improving food preparation and identifying personal tolerances.

Practical Steps to Reduce Lectin Exposure Safely

You don’t need to cut out entire food groups to manage lectin intake. Instead, focus on smart preparation and balanced eating.

- Always cook legumes thoroughly: Soak dried beans for at least 5 hours, discard the water, then boil vigorously for 10–15 minutes before simmering until tender.

- Choose fermented grains and soy: Opt for tempeh over tofu, sourdough bread over regular whole wheat, and naturally fermented soy sauces.

- Peel and deseed nightshades: Lectins concentrate in skins and seeds. Removing them can reduce exposure if sensitivity is suspected.

- Use a pressure cooker: This method is highly effective at deactivating lectins in beans and grains faster than conventional boiling.

- Rotate your plant foods: Avoid over-relying on a single lectin-rich food. Diversity supports gut resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can lectins cause weight gain?

There’s no direct evidence that lectins cause weight gain. In fact, lectin-rich foods like beans and whole grains are associated with better weight management due to their high fiber and protein content. Claims linking lectins to weight issues often stem from anecdotal reports, not clinical research.

Is a lectin-free diet necessary for good health?

No. For most people, a lectin-free diet is unnecessary and may lead to nutritional gaps. Whole grains, legumes, and vegetables provide essential nutrients and support long-term health. Unless advised by a healthcare provider due to specific conditions, eliminating these foods offers no proven advantage.

Are all lectins harmful?

No. Not all lectins are the same. Some, like those in raw kidney beans, are toxic in large amounts, while others—such as those in cooked tomatoes or oats—are present in negligible quantities and pose no known risk. The dose, preparation, and individual response determine the actual impact.

Conclusion: A Balanced Perspective on Lectins

Lectins are not inherently “bad”—they are part of many nutritious, life-promoting foods. The fear surrounding them often stems from oversimplification of complex biochemistry and extrapolation from animal studies. For the vast majority of people, properly prepared legumes, whole grains, and vegetables remain cornerstones of a healthy diet.

If you suspect lectins are affecting your health, work with a qualified nutritionist or doctor to assess your symptoms and explore dietary adjustments—without resorting to extreme restrictions. Knowledge, not elimination, is the key to sustainable wellness.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?