In an age where desk jobs dominate and screen time is at an all-time high, poor posture has become a widespread concern. Slouching over keyboards, craning necks toward phones, and prolonged sitting have led to a surge in back pain, shoulder tension, and spinal misalignment. In response, the market has flooded with posture correctors—brace-like garments designed to pull shoulders back and align the spine. But do they truly fix the problem, or are they masking symptoms while creating new ones? The answer isn’t as straightforward as marketing claims suggest.

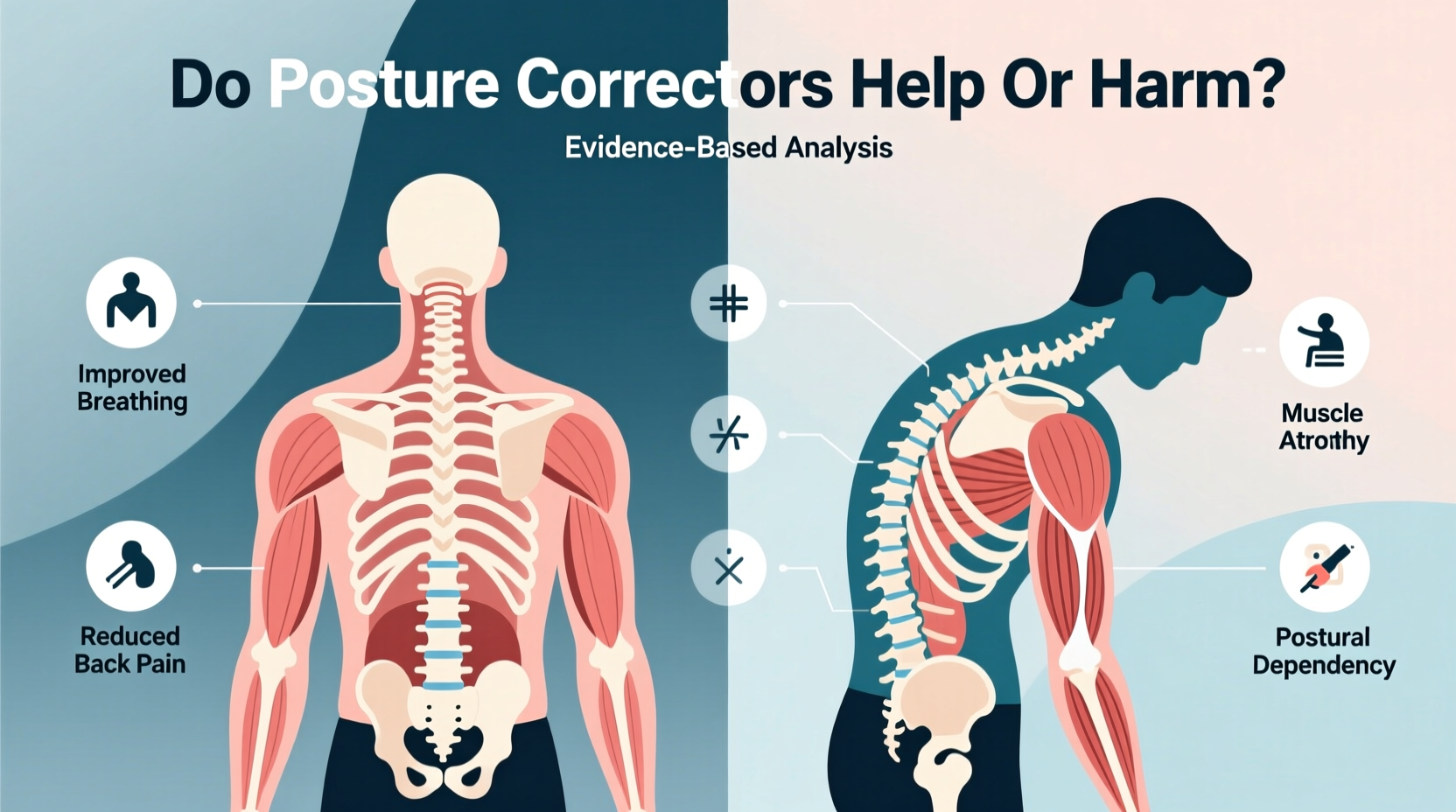

While many users report immediate relief and improved awareness of their posture, others experience discomfort, muscle weakness, or dependency. To understand whether posture correctors are allies or adversaries in spinal health, it’s essential to examine how they work, what science says about their effectiveness, and what alternatives exist for sustainable postural improvement.

How Posture Correctors Work: Mechanics vs. Muscle Memory

Posture correctors typically come in two forms: wearable braces (often resembling suspenders with straps across the shoulders) and adhesive devices that attach to the upper back. Their primary mechanism is mechanical correction—they physically pull the shoulders into a retracted position, forcing the chest open and the head back into alignment. This creates the appearance of better posture almost instantly.

The idea is rooted in biofeedback. By feeling the tension of the brace, wearers become more aware of when they’re slouching. Over time, this heightened awareness could theoretically help form better habits. However, this assumes that awareness alone leads to lasting change—a claim not consistently supported by clinical evidence.

Dr. Rebecca Lin, a physical therapist specializing in musculoskeletal rehabilitation, explains: “Posture correctors can be useful as short-term educational tools, but they don’t strengthen the muscles responsible for good posture. If you rely on them too much, your body may actually become dependent on external support.”

“Relying on a brace without addressing muscle imbalances is like using crutches for a sprained ankle forever—you never rebuild strength.” — Dr. Alan Torres, Orthopedic Rehabilitation Specialist

The Potential Benefits: When They Might Actually Help

Despite concerns, posture correctors aren’t universally harmful. In specific scenarios, they can serve a functional role:

- Short-term use during retraining: For individuals recovering from injury or beginning posture correction, a brace can act as a reminder to maintain alignment.

- Workplace ergonomics: Office workers transitioning to standing desks or adjusting monitor height may benefit from temporary feedback.

- Pain management: Some users with chronic upper back or neck pain report reduced discomfort when using a corrector intermittently.

- Awareness training: The tactile sensation helps break unconscious slouching patterns, especially in adolescents developing postural habits.

A 2020 pilot study published in the *Journal of Physical Therapy Science* found that participants who used a posture corrector for 30 minutes daily over four weeks showed measurable improvements in forward head posture and shoulder angle. However, these gains plateaued after six weeks, and no long-term follow-up was conducted to assess retention.

The Hidden Risks: How Overuse Can Backfire

The real danger lies not in occasional use, but in prolonged or improper reliance. When worn for hours every day, posture correctors can interfere with natural muscle function and lead to unintended consequences.

Muscle Atrophy and Dependency

The muscles of the upper back—particularly the rhomboids, lower trapezius, and serratus anterior—are designed to hold the shoulders in a neutral position. When a brace does this job instead, those muscles receive less activation. Over time, they weaken through disuse, making it harder to maintain good posture without the device.

This phenomenon, known as \"muscle inhibition,\" mirrors issues seen with prolonged use of back braces in lumbar support. The body adapts to external stabilization by reducing internal effort, leading to a cycle of increasing dependence.

Joint and Nerve Irritation

Tight straps across the shoulders can compress nerves in the brachial plexus, leading to tingling, numbness, or weakness in the arms. Some users report increased tension in the neck and upper traps due to overcorrection—pulling the shoulders too far back forces the cervical spine into extension, potentially worsening neck strain.

False Sense of Security

Wearing a corrector can create the illusion of progress without actual behavioral change. Users might feel “fixed” while still sitting poorly, neglecting ergonomic adjustments or movement breaks. Once the brace comes off, old habits return—often with added stiffness from restricted motion.

Do’s and Don’ts of Using Posture Correctors

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Use for 20–30 minutes at a time, max 1–2 times per day | Wear for more than 2 hours continuously |

| Combine with active posture exercises (e.g., scapular retractions) | Rely solely on the device without strengthening muscles |

| Choose adjustable, breathable designs with padded straps | Use overly tight models that restrict breathing or movement |

| Pair with ergonomic workspace setup | Sit longer just because you're wearing the brace |

| Discontinue use if pain, numbness, or discomfort occurs | Ignore warning signs of nerve compression or muscle fatigue |

A Better Path: Building Sustainable Posture Through Movement

If posture correctors offer only temporary fixes, what’s the alternative? Long-term postural health depends not on external devices, but on internal strength, mobility, and habit formation. The human body evolved to move, not to be held rigidly in place by fabric and elastic.

True postural correction involves three key components: neuromuscular re-education, targeted strengthening, and environmental optimization.

Step-by-Step Guide to Natural Posture Improvement

- Assess Your Daily Habits: Track how often you sit, where your screens are positioned, and when you take movement breaks. Identify major contributors to slouching.

- Optimize Ergonomics: Adjust chair height so feet rest flat, position monitors at eye level, and use a lumbar roll if needed.

- Strengthen Postural Muscles: Perform daily exercises such as:

- Wall angels (3 sets of 10)

- Prone Y-T-W raises (2 sets of 8 each)

- Rows with resistance bands (3 sets of 12)

- Improve Thoracic Mobility: Spend 5 minutes daily on foam rolling or cat-cow stretches to reduce stiffness in the upper back.

- Practice Mindful Alignment: Set hourly reminders to check posture. Stand tall, retract shoulders gently, and engage core lightly.

- Move Frequently: Take a 2–3 minute walk every hour. Movement resets muscle tone and prevents static loading.

Real-World Example: From Braces to Strength

Consider the case of Marcus, a 34-year-old software developer who began experiencing chronic upper back pain after transitioning to remote work. He purchased a popular posture corrector online and wore it for 4–6 hours daily. Initially, his pain decreased and he felt more upright. But after six weeks, he noticed new discomfort in his shoulders and arms, along with increased fatigue.

Upon visiting a physical therapist, Marcus learned he had developed significant weakness in his scapular stabilizers. His reliance on the brace had suppressed muscle activation. Under guided care, he discontinued the corrector and began a 12-week program focused on scapular control and thoracic extension. By week eight, his pain had resolved, and he reported feeling stronger and more balanced—even after long coding sessions.

“I thought the brace was fixing me,” Marcus said. “But it was actually hiding the real issue: I wasn’t moving enough and my muscles were asleep.”

Expert Consensus: What Health Professionals Recommend

Most physical therapists and spine specialists agree: posture correctors should be viewed as optional tools—not solutions. Their value lies in education, not correction.

“We sometimes use braces in clinical settings to teach patients what neutral posture feels like. But within two weeks, we shift focus to exercise and movement. That’s where real change happens.” — Dr. Lena Park, DPT, Certified Spinal Specialist

The American Physical Therapy Association emphasizes active interventions over passive supports. Their guidelines recommend individualized assessment, targeted strengthening, and ergonomic modification as first-line approaches for postural dysfunction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can posture correctors fix kyphosis or rounded shoulders?

Not permanently. While they may temporarily reduce the appearance of rounded shoulders, they do not address the underlying muscular imbalances or joint restrictions that contribute to kyphosis. Structural changes require consistent exercise, mobility work, and sometimes medical intervention.

How long should I wear a posture corrector?

No more than 20–30 minutes at a time, and only for short durations (e.g., 1–2 weeks) as part of a broader posture improvement plan. Prolonged use increases the risk of muscle weakening and dependency.

Are there any safe alternatives to posture braces?

Yes. Options include ergonomic chairs with lumbar support, taping techniques (like kinesiology tape applied by a professional), and wearable sensors that vibrate when you slouch—providing feedback without physical restriction.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Fix-It-Now Mentality

The appeal of posture correctors is understandable—they promise quick results in a world where time is scarce and discomfort is common. But sustainable posture isn’t something that can be strapped into place. It’s built through consistent movement, mindful alignment, and muscular resilience.

Instead of seeking shortcuts, invest in practices that empower your body to support itself. Strengthen your postural muscles, optimize your environment, and cultivate awareness throughout the day. These efforts may take longer than slipping on a brace, but they deliver lasting results without the risk of dependency.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?