Squats are one of the most effective exercises for building lower-body strength, improving mobility, and enhancing athletic performance. Yet, a persistent myth continues to circulate: that squats are inherently harmful to the knees. This misconception often deters people from incorporating one of the most functional movements into their fitness routines. The truth is, when performed with proper technique, squats are not only safe for the knees—they can actually strengthen the joint, improve stability, and reduce long-term injury risk.

The key lies in execution. Poor form, excessive loading, or ignoring biomechanical cues can place undue stress on the knee joint, leading to pain or injury. On the other hand, mastering correct squat mechanics transforms this compound movement into a joint-supportive powerhouse. This article breaks down the science behind knee safety during squats, outlines common mistakes, and provides actionable strategies to perform squats effectively and safely—no matter your fitness level.

The Science Behind Squats and Knee Health

Contrary to popular belief, research consistently shows that properly executed squats do not damage the knees. In fact, studies published in the *Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research* indicate that deep, controlled squats increase knee stability by strengthening the quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and surrounding connective tissues. These muscles act as shock absorbers and dynamic stabilizers, reducing strain on the joint itself.

One critical finding is that compressive forces on the knee peak at around 90 degrees of flexion and actually decrease as you go deeper into the squat. This means that going below parallel (a full-depth squat) may be safer than stopping halfway—provided form is maintained. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), often a concern during knee-dominant movements, experiences minimal stress during back squats due to balanced muscle activation and natural joint alignment.

“Squats, when done correctly, promote joint health by increasing blood flow to the connective tissues and reinforcing neuromuscular control.” — Dr. Michael Clark, DPT, Orthopedic Performance Specialist

The real danger arises not from the squat itself, but from compensatory patterns: letting the knees cave inward, shifting too much weight forward onto the toes, or rounding the lower back. These errors transfer load from muscles to passive joint structures like ligaments and cartilage, increasing injury risk over time.

Common Form Mistakes That Harm the Knees

Even well-intentioned lifters can unknowingly compromise their knee health by repeating subtle errors. Recognizing these missteps is the first step toward correction.

- Knee Valgus (Inward Collapse): When the knees dip inward during descent or ascent, it places torsional stress on the ACL and medial meniscus. This is often caused by weak glutes or poor hip control.

- Heels Lifting Off the Ground: Rising onto the toes shifts weight forward, increasing shear force on the patella (kneecap). It also reduces posterior chain engagement, making the quads bear disproportionate load.

- Excessive Forward Lean: While some forward torso inclination is normal, excessive lean—especially in front squats or goblet variations—can alter knee tracking and compress the patellofemoral joint.

- Rounded Lower Back (Lumbar Flexion): A compromised spine disrupts pelvic alignment, which in turn affects knee positioning. This creates a chain reaction of instability through the kinetic chain.

- Starting with Knees First: Many beginners initiate the movement by bending the knees before hinging at the hips, leading to a “quad-dominant” squat that overloads the patellar tendon.

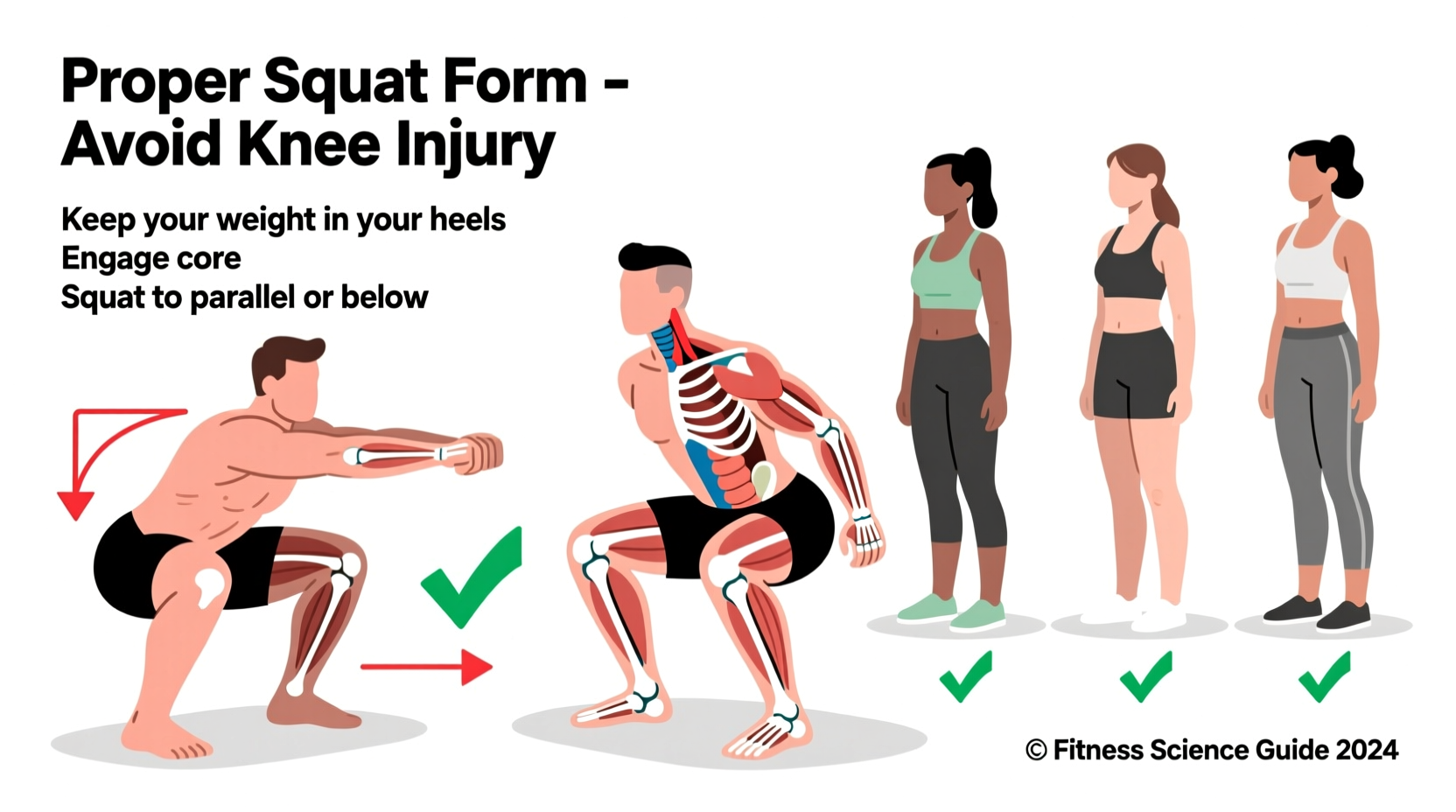

Step-by-Step Guide to Proper Squat Form

Mastering the squat requires attention to detail across multiple phases. Follow this progression to build confidence and precision.

- Set Your Stance: Feet shoulder-width apart or slightly wider, toes pointed slightly outward (5–15 degrees). Distribute weight evenly across the entire foot—heel, ball, and little toe.

- Engage Your Core: Brace your abdominal muscles as if preparing for a light punch. This stabilizes the spine and supports intra-abdominal pressure.

- Initiate the Hip Hinge: Begin the descent by pushing your hips back, as if sitting into a chair. This engages the posterior chain early and prevents knee dominance.

- Control the Descent: Lower yourself slowly (2–3 seconds), keeping your chest up and spine neutral. Track your knees over your toes—do not let them drift past your shoelaces excessively.

- Reach Depth Safely: Aim to break parallel (hip crease below knee) if mobility allows. If depth is limited, work on ankle, hip, and thoracic spine mobility rather than forcing range.

- Drive Through the Heels: Push through the entire foot, focusing on driving the heels into the ground. Extend hips and knees simultaneously to return to standing.

- Lock Out with Glute Squeeze: At the top, fully extend the hips and contract the glutes to prevent hyperextension of the lumbar spine.

“Think ‘hips back, chest up, knees out’—this mantra reinforces three critical alignment cues.” — Coach Sarah Lin, CSCS

Do’s and Don’ts of Knee-Safe Squatting

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Keep knees aligned with toes | Let knees collapse inward (valgus) |

| Maintain a neutral spine throughout | Round or overarch your lower back |

| Use a box or bench to practice depth | Force depth without adequate mobility |

| Wear flat or minimally cushioned shoes | Squat in thick, elevated-heeled sneakers unless required for sport |

| Warm up hips, ankles, and thoracic spine | Jump straight into heavy squats cold |

| Progress load gradually (5–10% per week) | Add weight too quickly without mastering form |

Tips to Prevent Knee Pain and Build Joint Resilience

Long-term knee health in squatters depends not just on form, but on preparation, recovery, and programming. Integrate these evidence-based strategies into your routine.

- Strengthen Supporting Muscles: Incorporate exercises like clamshells, banded walks, and single-leg deadlifts to enhance glute medius and hamstring function, which help control knee alignment.

- Use Tempo Variations: Slow eccentrics (e.g., 4-second descent) increase time under tension and improve motor control, reducing jerky movements that stress joints.

- Scale Intensity Based on Feedback: If you experience sharp knee pain—not to be confused with normal muscle fatigue—reduce load or volume. Pain is a signal, not a challenge to overcome.

- Optimize Recovery: Prioritize sleep, hydration, and nutrition rich in collagen-supportive nutrients (vitamin C, glycine, proline) to maintain healthy tendons and cartilage.

- Listen to Your Body’s Limits: Some individuals have anatomical variations (e.g., femoral acetabular impingement, shallow hip sockets) that limit squat depth. Respect individual biomechanics—there’s no universal “perfect” squat.

Real Example: Recovering From Knee Discomfort Through Technique Adjustment

Mark, a 38-year-old office worker, began experiencing sharp pain beneath his kneecap after starting a home workout program. He was performing bodyweight squats daily, believing deeper was always better. Despite consistent effort, the discomfort worsened, especially when climbing stairs.

After consulting a physical therapist, Mark discovered two primary issues: excessive forward knee travel due to tight ankles and weak glutes causing valgus collapse. His program shifted focus—he stopped high-rep squats and instead began with wall squats, heel-elevated goblet squats, and targeted glute activation drills.

Over six weeks, he gradually reintroduced back squats with lighter loads, emphasizing hip hinge mechanics and knee alignment. He also incorporated daily ankle mobility work using a resistance band stretch. By week eight, his knee pain had resolved, and he successfully performed unweighted bodyweight squats with full depth and control.

Mark’s case illustrates that knee pain during squats is rarely a reason to abandon the movement—it’s usually a cue to reassess form, mobility, and programming.

Checklist for Safe, Effective Squatting

Use this checklist before each squat session to ensure optimal joint protection and performance:

- ✅ Warm up hips, ankles, and thoracic spine with dynamic stretches

- ✅ Check footwear—opt for flat-soled shoes or barefoot if surface permits

- ✅ Engage core and set neutral spine before initiating movement

- ✅ Initiate descent with hips, not knees

- ✅ Keep knees tracking over middle toes throughout range

- ✅ Maintain heel contact with the floor

- ✅ Control tempo—avoid bouncing at the bottom

- ✅ Gradually increase load only after mastering form

- ✅ Monitor for any sharp or localized knee pain post-session

- ✅ Cool down with light stretching for quads, hamstrings, and hip flexors

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I squat with existing knee pain or past injuries?

Many people with prior knee issues can safely squat under professional guidance. Conditions like patellar tendinopathy or mild osteoarthritis often respond well to controlled, progressive loading. However, acute inflammation or post-surgical recovery requires medical clearance. Work with a physical therapist to modify depth, load, or type (e.g., leg press vs. free-weight squat) based on your diagnosis.

Is it safe to let my knees go past my toes?

Yes—within reason. The outdated rule that knees must never pass the toes is overly restrictive and not supported by biomechanics. Allowing moderate forward knee translation is natural, especially in taller individuals or those with longer femurs. The priority is maintaining balance over the mid-foot and avoiding excessive shear force through control and strength, not arbitrary spatial limits.

What’s better for knees: front squats or back squats?

Both can be knee-friendly when performed correctly. Front squats typically require more upright torso positioning, reducing forward knee travel and shear force on the patella. They’re often recommended for those with knee sensitivity. Back squats allow heavier loading and greater glute/hamstring activation but demand more hip and ankle mobility. Choose based on comfort, goals, and mobility profile.

Conclusion: Squats Are Allies, Not Enemies, to Knee Health

The idea that squats are bad for your knees is a myth rooted in misunderstanding and poor execution. When performed with attention to biomechanics, appropriate progression, and individual limitations, squats enhance joint stability, muscular balance, and functional strength. They are not merely safe—they are therapeutic for many who suffer from knee weakness or instability.

Improving your squat isn’t about lifting the heaviest weight possible. It’s about moving with intention, respecting your body’s signals, and building resilience over time. Whether you're a beginner or an experienced lifter, refining your form and prioritizing joint health will pay dividends far beyond the gym.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?