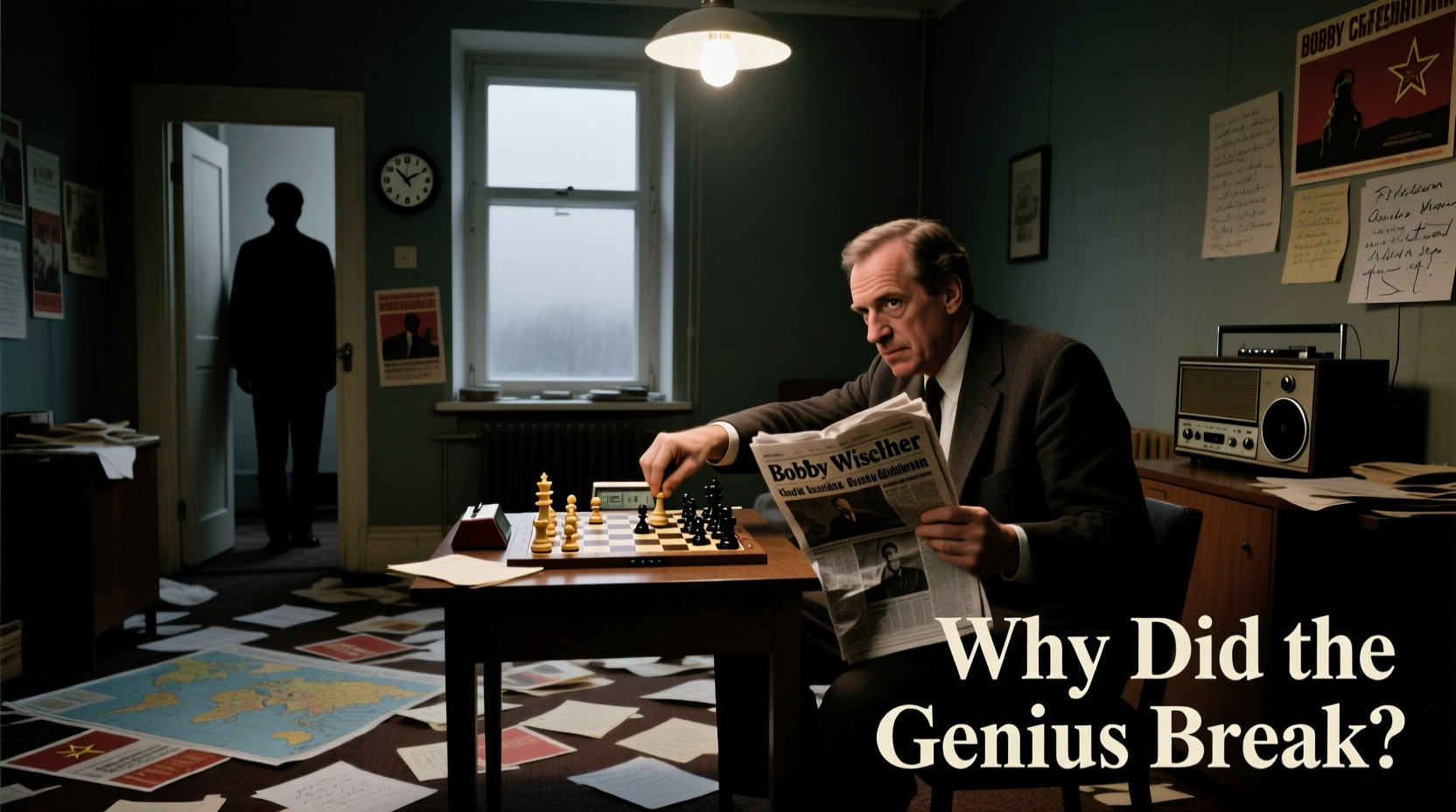

Bobby Fischer remains one of the most brilliant minds in the history of competitive chess. His 1972 World Championship victory over Boris Spassky was not just a personal triumph—it was a geopolitical event during the Cold War, elevating Fischer to global stardom. Yet, his meteoric rise was matched by an equally dramatic descent into reclusiveness, conspiracy theories, and public outbursts. The question persists: Why did such a towering intellectual force exhibit increasingly erratic behavior? The answer lies at the intersection of psychological complexity, early-life trauma, social alienation, and possibly undiagnosed mental health conditions.

The Making of a Prodigy: Early Life and Isolation

Fischer’s journey began under unusual circumstances. Born in 1943 in Chicago, he was raised primarily by his mother, Regina Fischer, a polymath with degrees in medicine and nursing. His father was absent from his life early on, creating a household dominated by intellectual ambition but lacking emotional stability. By age six, Bobby discovered chess through a set in his Brooklyn apartment. Within months, he was playing with intensity that bordered on obsession.

By 13, he won the U.S. Junior Chess Championship. At 14, he became the youngest U.S. Champion in history—a record that stood for decades. This rapid ascent came at a cost. Fischer skipped traditional schooling, withdrew from peer relationships, and lived almost entirely within the confines of chess. Psychologists note that such extreme specialization in childhood, especially without balanced social development, can lead to emotional rigidity and difficulty coping with ambiguity or criticism later in life.

Patterns of Paranoia and Perfectionism

Fischer’s playstyle mirrored his personality—precise, uncompromising, and relentless. He demanded absolute control over tournament conditions, insisting on specific clocks, seating arrangements, and even lighting. In the 1972 World Championship, he nearly forfeited the match due to disputes over prize money and camera noise. While some dismissed this as arrogance, it reflected a deeper need for order in a world he perceived as chaotic.

After winning the title, Fischer vanished from public competition. He never defended his championship, forfeiting it to Anatoly Karpov in 1975. For years, he lived off royalties and sporadic appearances, growing increasingly suspicious of institutions, particularly those tied to government or media. His rhetoric turned conspiratorial—he railed against Jewish influence (despite being half-Jewish himself), denounced the U.S. government, and praised anti-Semitic and anti-American figures.

“He didn’t just dislike losing—he couldn’t tolerate imperfection, whether in moves or in people. That kind of mind doesn’t easily accept a flawed world.” — Dr. Naomi Weisstein, cognitive psychologist specializing in high-IQ individuals

Possible Psychological Underpinnings

No formal diagnosis was ever confirmed during Fischer’s lifetime, but retrospective analysis by psychiatrists and biographers suggests several possibilities:

- Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD): Characterized by rigid adherence to rules, perfectionism, and emotional constriction.

- Paranoid Personality Disorder: Marked by pervasive distrust and suspicion of others, interpreting motives as malevolent.

- Schizotypal Traits: Social detachment, eccentric beliefs, and magical thinking—seen in Fischer’s fixation on numerology and apocalyptic predictions.

It’s important to distinguish these from schizophrenia; Fischer maintained logical coherence and goal-directed behavior, even when espousing extreme views. Instead, his worldview appeared filtered through a lens of hyper-rationality twisted by isolation and fear.

Contributing Factors to Fischer’s Decline

| Factor | Description | Impact on Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Childhood Isolation | Limited peer interaction, homeschooling, intense focus on chess | Hindered social adaptability and emotional regulation |

| Absent Father Figure | Biological father not involved; identity confusion | May have contributed to trust issues and identity instability |

| Media Overexposure | Global fame after 1972, constant scrutiny | Increased pressure and sense of vulnerability |

| Political Climate | Cold War tensions, FBI surveillance | Reinforced real and imagined persecution |

| Religious Extremism | Influence of the Worldwide Church of God | Shaped apocalyptic worldview and anti-establishment stance |

A Turning Point: The 1992 Return and Exile

In 1992, Fischer resurfaced to play a $5 million rematch against Spassky in war-torn Yugoslavia—a country under U.S. sanctions. The U.S. government issued a warning, then a warrant, for violating economic sanctions. Fischer ignored it, played the match, and won. But the fallout was irreversible. He became a fugitive, living in Hungary, the Philippines, and finally Iceland, which granted him citizenship in 2005.

This period marked the peak of his erratic public persona. In a 2001 radio interview, he celebrated the 9/11 attacks, calling them “wonderful news” and expressing hatred for America. These statements shocked former friends and fans, many of whom had hoped he would return gracefully to public life.

Mini Case Study: The Radio Interview That Ended His Legacy

In a 2001 broadcast on a Filipino station, Fischer spent hours ranting about Jewish control of chess, American imperialism, and the brilliance of Hitler’s military strategy. When asked about 9/11, he responded: “I applaud the act… I wish they’d do it again.” These comments were not isolated—they were part of a broader pattern of dehumanizing rhetoric. What made this moment significant was its permanence. Unlike private letters or obscure pamphlets, this was public, recorded, and widely circulated.

Former U.S. Chess Federation president Burt Hochberg later said, “It was like watching a cathedral burn down from the inside. The mind that calculated twenty moves ahead couldn’t see the moral abyss it was entering.”

Legacy and Lessons: Genius, Madness, and Society’s Role

Fischer’s story is not merely one of decline—it’s a cautionary tale about how society treats its outliers. We celebrate genius but often fail to support the fragile ecosystems that sustain it. Fischer was given resources to train, compete, and win—but not to heal, connect, or grow beyond the board.

His later years, spent in Reykjavik under police protection and battling illness, were quiet but unresolved. He died in 2008 of kidney failure, having never reconciled with the world that once adored him.

Checklist: Supporting High-Ability Individuals Without Causing Harm

- Encourage balanced development—academics, arts, physical activity, and social skills.

- Monitor for signs of social withdrawal or obsessive behaviors.

- Provide access to counseling or psychological support early.

- Avoid over-publicizing achievements; protect privacy during formative years.

- Foster environments where mistakes are seen as learning opportunities, not failures.

- Engage mentors who model emotional intelligence alongside expertise.

FAQ

Did Bobby Fischer have a mental illness?

While never officially diagnosed, behavioral patterns suggest possible paranoid personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive traits. His delusional beliefs and hostility toward institutions align with clinical descriptions, though speculation must remain cautious without medical records.

Why did Fischer hate the U.S. despite becoming a national hero?

His resentment stemmed from multiple sources: feeling exploited by chess organizations, anger over financial disputes, belief in government surveillance, and ideological radicalization. His time with the Worldwide Church of God also instilled deep anti-government and apocalyptic views.

Could Fischer’s decline have been prevented?

Possibly. With structured psychological support, reduced media pressure, and a community focused on holistic growth rather than performance alone, his trajectory might have been different. However, his inherent temperament made integration into conventional support systems difficult.

Conclusion: Beyond the Board

Bobby Fischer’s erratic behavior cannot be reduced to a single cause. It emerged from a confluence of extraordinary talent, emotional deprivation, societal pressure, and ideological extremism. He was not mad in the theatrical sense, but profoundly alienated—trapped between a mind capable of mastering any position on a chessboard and an inability to navigate the unpredictable game of human connection.

His legacy challenges us to rethink how we nurture genius. Excellence should not require sacrifice of sanity or humanity. As we continue to idolize prodigies in science, art, and sport, let Fischer’s life serve as a reminder: the mind needs more than puzzles to thrive.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?