Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a complex mental health condition characterized by emotional instability, impulsive behavior, intense interpersonal relationships, and a fragile sense of self. While BPD does not directly shorten life in the way certain physical illnesses do, growing evidence shows that individuals with BPD face a significantly higher risk of premature death compared to the general population. Understanding the factors behind this increased mortality—and how they can be mitigated—is essential for improving long-term outcomes.

This article examines current research on BPD life expectancy, explores the primary contributors to reduced longevity, and outlines practical steps that patients, families, and clinicians can take to support better health and extended lifespan.

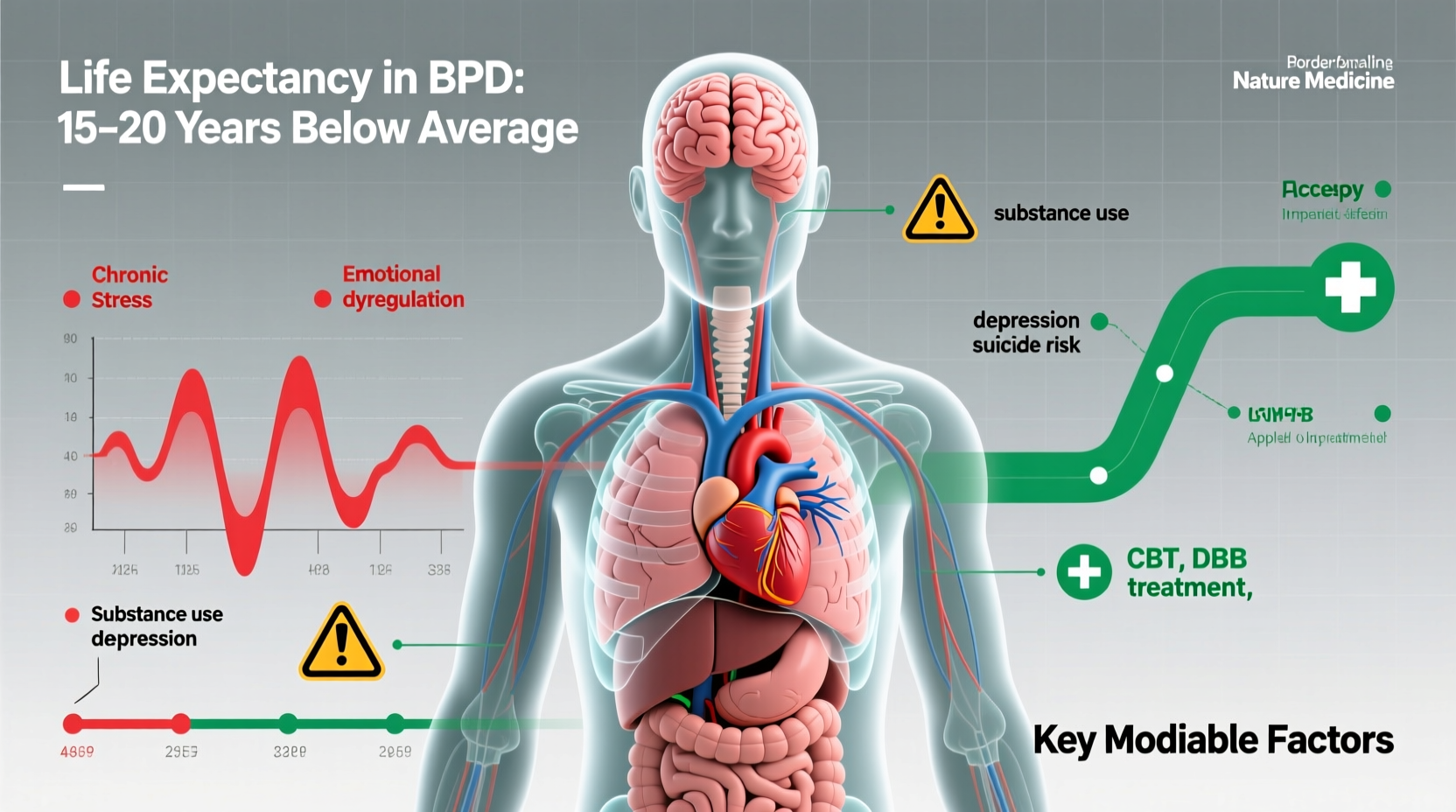

The Reality of Life Expectancy in BPD

Multiple longitudinal studies have shown that people diagnosed with BPD have a life expectancy that is, on average, 10 to 20 years shorter than the general population. A landmark study published in the *Journal of Clinical Psychiatry* followed over 290 individuals with BPD for two decades and found a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) of 4.6—meaning they were nearly five times more likely to die prematurely than their peers without the disorder.

The causes of early death are multifaceted: suicide accounts for a significant portion, but accidental deaths, substance-related complications, and co-occurring medical conditions also play major roles. Notably, while suicide rates are highest in early adulthood, the risk remains elevated throughout life, especially during periods of untreated symptoms or social isolation.

Key Factors Affecting Longevity in BPD

Several interrelated factors contribute to the shortened life expectancy observed in individuals with BPD. These span psychological, behavioral, social, and biological domains.

1. Suicide and Self-Harm

Suicidal behavior is one of the most pressing concerns in BPD. Approximately 70% of individuals with BPD will attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime, and about 8–10% will die by suicide—rates far exceeding those of most other psychiatric disorders.

Self-harm, while not always lethal, increases vulnerability to accidental death and often signals deep emotional distress that requires urgent intervention.

2. Co-Occurring Mental Health Disorders

BPD rarely exists in isolation. Common comorbidities include major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, PTSD, eating disorders, and substance use disorders. Each of these conditions independently increases mortality risk, and when combined with BPD, the cumulative effect is substantial.

For example, individuals with both BPD and opioid use disorder face drastically higher risks of overdose and infectious disease due to risky behaviors and inconsistent healthcare engagement.

3. Physical Health Complications

Chronic stress, poor self-care habits, and side effects from psychiatric medications contribute to long-term physical health decline. Research indicates higher rates of:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Type 2 diabetes

- Obesity

- Chronic pain syndromes

- Weakened immune function

These conditions are often underdiagnosed because individuals with BPD may avoid medical settings due to past trauma or fear of judgment.

4. Social and Economic Challenges

Unstable employment, housing insecurity, legal issues, and fractured relationships amplify stress and limit access to care. Social isolation—especially after repeated relationship breakdowns—can lead to disengagement from treatment and reduced motivation for self-preservation.

“People with BPD are not inherently fragile; they’re responding to overwhelming emotions with limited coping tools. With proper support, recovery and sustained wellness are absolutely possible.” — Dr. John Gunderson, Harvard Medical School, pioneer in BPD research

What the Research Tells Us

Longitudinal data offers hope. Contrary to earlier assumptions that BPD is a lifelong, unchangeable condition, modern studies show high rates of remission. The McLean Study of Adult Development found that after 10 years, over 75% of participants achieved symptom remission lasting at least two years, and 88% eventually reached remission over 16 years.

However, remission doesn’t automatically equate to full functional recovery. Many individuals continue to struggle with employment, relationships, and physical health even after emotional symptoms improve. This underscores the need for holistic, long-term care models.

A 2021 meta-analysis in *The Lancet Psychiatry* concluded that dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and schema-focused therapy not only reduce self-harm and hospitalization but also improve overall quality of life and treatment adherence—factors linked to longer survival.

Table: Risk Factors and Their Impact on BPD Life Expectancy

| Risk Factor | Impact on Mortality | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Suicidal behavior | High – leading cause of early death | DBT, safety planning, crisis response training |

| Substance use disorder | Very High – overdose, organ damage | Integrated dual diagnosis treatment |

| Chronic stress & inflammation | Moderate – contributes to heart disease, diabetes | Mindfulness, exercise, trauma-informed care |

| Social isolation | Moderate – reduces help-seeking and resilience | Peer support groups, community integration |

| Poor medical engagement | High – delays diagnosis and treatment of physical illness | Coordinated care between mental and physical health providers |

Real-Life Example: A Path Toward Stability

Consider the case of Maria, diagnosed with BPD at age 24 after multiple ER visits for self-harm and a suicide attempt. She struggled with binge drinking, unstable jobs, and volatile relationships. After entering a DBT program, she began weekly therapy, joined a peer support group, and started working with a primary care provider who specialized in trauma-informed medicine.

Over five years, Maria’s suicidal ideation decreased significantly. She maintained sobriety, secured stable housing, and eventually returned to school. While she still experiences emotional fluctuations, she now has tools to manage them. Most importantly, she no longer feels trapped by her diagnosis.

Maria’s story illustrates that while BPD presents serious risks, structured treatment and compassionate support systems can dramatically alter life trajectory.

Action Plan: Improving Long-Term Outcomes

Improving life expectancy in BPD isn’t just about preventing suicide—it’s about building a life worth living. The following checklist outlines concrete steps for individuals, caregivers, and clinicians.

Checklist: Supporting Longevity in BPD

- Seek evidence-based therapy (e.g., DBT, MBT, or schema therapy)

- Establish a crisis plan with emergency contacts and coping strategies

- Engage a primary care physician for regular health screenings

- Treat co-occurring disorders (e.g., depression, addiction) simultaneously

- Build a support network through support groups or trusted relationships

- Practice daily self-care: sleep hygiene, nutrition, gentle movement

- Use medication only as prescribed and under close monitoring

- Advocate for integrated care that bridges mental and physical health services

Frequently Asked Questions

Can BPD be cured?

While “cure” is a complex term in mental health, many people with BPD experience full remission of symptoms and go on to live fulfilling lives. Recovery is often gradual and requires consistent effort, but it is absolutely achievable. Long-term studies confirm that the majority of individuals see significant improvement over time.

Does medication extend life expectancy in BPD?

There is no medication specifically approved to treat BPD core symptoms. However, certain medications—like mood stabilizers or antidepressants—can help manage co-occurring conditions such as depression or impulsivity. When used appropriately within a broader treatment plan, they may indirectly support longevity by reducing symptom severity and improving functioning.

Is life expectancy improving for people with BPD?

Yes. As awareness grows and access to effective therapies expands, outcomes are steadily improving. Early intervention, reduced stigma, and integrated care models are contributing to longer, healthier lives. Continued investment in research and accessible treatment is key to further progress.

Conclusion: A Future Worth Investing In

The statistics surrounding BPD life expectancy are sobering, but they should not define an individual’s future. With timely, compassionate, and sustained care, people with BPD can achieve stability, build meaningful relationships, and enjoy good health well into later life.

Understanding the risks is only the first step. The real work lies in creating systems of support—clinical, familial, and societal—that empower individuals to heal and thrive. Whether you’re navigating BPD yourself or supporting someone who is, know that every positive choice matters. Recovery is not linear, but it is possible.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?