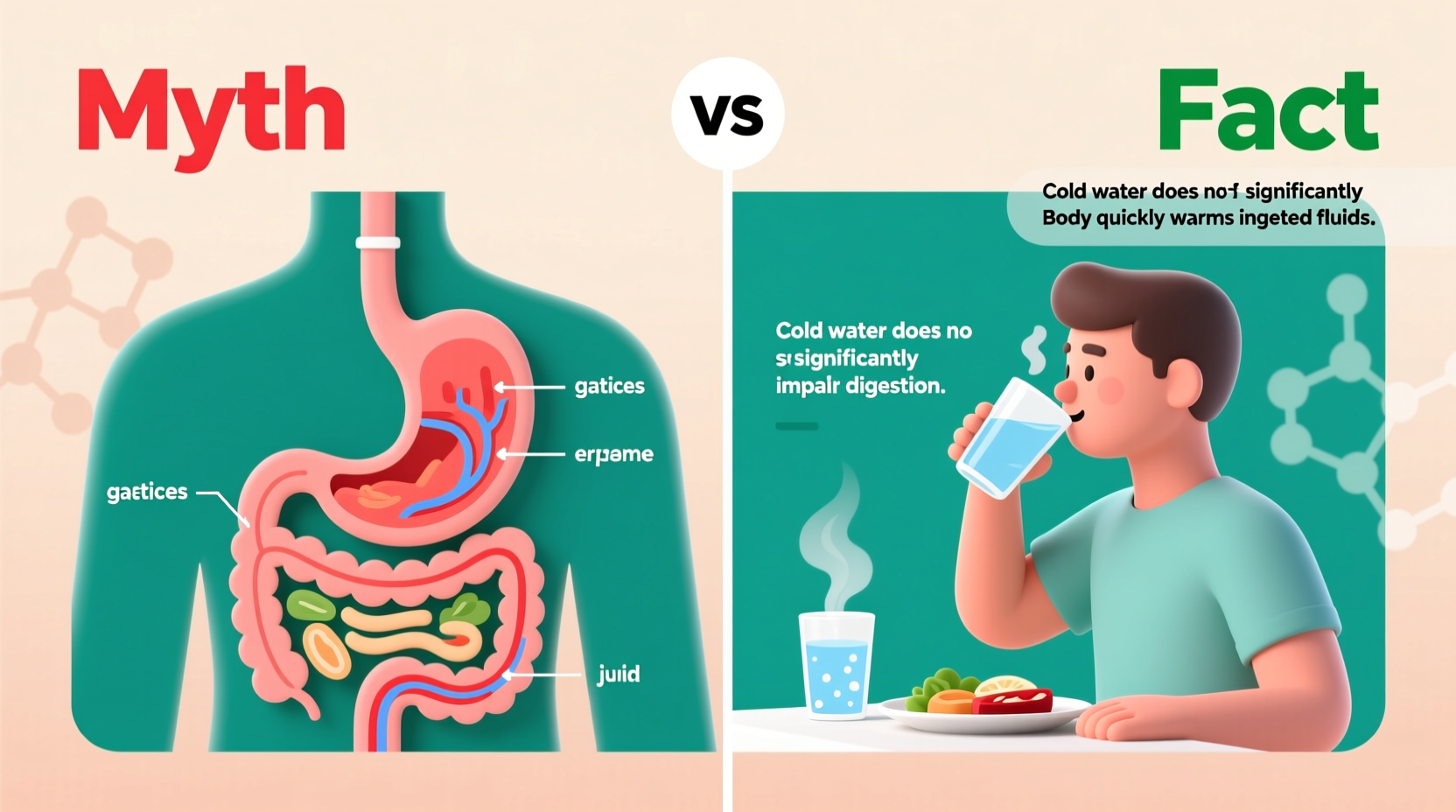

For decades, a persistent belief has circulated across wellness circles, traditional medicine systems, and dinner tables: drinking cold water immediately after a meal can disrupt digestion. Advocates of warm or room-temperature water argue that icy liquids shock the stomach, congeal fats, slow digestive enzymes, and ultimately lead to bloating, indigestion, or long-term health issues. But how much of this is grounded in science, and how much is simply cultural folklore? As modern nutrition science advances, it’s time to critically assess whether this widely shared advice holds up—or if it's merely an enduring myth.

The truth is more nuanced than a simple yes or no. While certain traditional practices offer valuable insights into holistic well-being, physiological evidence on cold water’s impact on digestion reveals a different story—one shaped by human adaptability, individual variation, and the robust nature of our digestive system.

The Digestive Process: How Temperature Plays a Role

Digestion begins in the mouth with mechanical chewing and enzymatic action from saliva. Once food reaches the stomach, gastric acids and enzymes like pepsin break down proteins, while muscular contractions churn the contents into chyme. From there, the small intestine continues the process with bile and pancreatic enzymes, absorbing nutrients efficiently under tightly regulated conditions.

One key factor in this process is temperature. The human body maintains a core temperature of approximately 98.6°F (37°C), and the digestive tract operates optimally within this range. When cold substances enter the stomach, the organ must expend energy to bring them up to body temperature. This thermoregulatory adjustment is automatic and typically seamless.

However, does this minor thermal shift actually impair digestion? Research suggests not. A 2007 study published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology found no significant difference in gastric emptying time between subjects who consumed cold versus room-temperature water during meals. Similarly, a review in the European Journal of Applied Physiology noted that moderate intake of cold fluids did not hinder gastrointestinal function in healthy individuals.

“While extreme temperatures may cause temporary discomfort, the human digestive system is remarkably resilient and capable of handling variations in fluid temperature without functional impairment.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Gastroenterologist and Nutrition Researcher

Origins of the Myth: Ayurveda and Traditional Beliefs

The idea that cold water harms digestion originates largely from Ayurvedic medicine, an ancient Indian healing system. In Ayurveda, digestion is governed by “Agni,” or digestive fire. Cold water is believed to dampen Agni, leading to incomplete digestion, toxin accumulation (known as “ama”), and imbalances in the body’s doshas (energetic forces).

This perspective isn’t entirely without merit. Ayurveda emphasizes personalized health based on constitution (Vata, Pitta, Kapha), season, and lifestyle. For individuals with a dominant Kapha dosha—associated with coolness, heaviness, and sluggish metabolism—cold water might contribute to feelings of lethargy or bloating. In colder climates or seasons, warm fluids are naturally more soothing and may support circulation and metabolic activity.

Yet, Ayurvedic principles were developed in a specific cultural and environmental context. Applying them universally without considering modern physiology or individual differences risks overgeneralization. While warm water may enhance comfort for some, equating cold water with digestive harm lacks consistent scientific validation.

Scientific Evidence: What Does the Research Say?

To date, no high-quality clinical trials have demonstrated that cold water impairs nutrient absorption, enzyme activity, or overall digestive efficiency in healthy adults. The stomach’s ability to regulate its internal environment ensures that ingested substances quickly reach thermal equilibrium.

One area where temperature may matter is fat digestion. Some claim that cold water causes dietary fats to solidify, making them harder to break down. However, this theory misunderstands human physiology. Dietary fats are emulsified by bile in the small intestine at body temperature, regardless of initial fluid temperature. There is no evidence that cold water leads to fat “congealing” in the stomach.

In contrast, certain populations may benefit from warmer fluids. A 2013 study in the Indian Journal of Critical Care observed that postoperative patients who consumed warm water experienced faster gastric motility than those given cold water. Similarly, individuals with functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) sometimes report symptom relief when avoiding very cold beverages.

Still, these findings don’t support a blanket recommendation against cold water. They highlight the importance of individual sensitivity rather than universal risk.

Do’s and Don’ts: Fluid Consumption Around Meals

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Drink water before or during meals to aid swallowing and prevent overeating | Chug large volumes of any liquid right after eating, as this may distend the stomach |

| Choose room-temperature or warm water if you have digestive sensitivities | Assume cold water is harmful for everyone—individual responses vary |

| Stay hydrated throughout the day to support overall digestive health | Rely solely on temperature myths instead of addressing root causes of indigestion |

| Observe how your body responds to different fluid temperatures | Ignore symptoms like bloating or cramping—consult a healthcare provider if persistent |

Real-Life Example: A Case Study in Personal Response

Sophie, a 34-year-old office worker from Chicago, had struggled with post-meal bloating for years. She followed various wellness blogs recommending warm lemon water after meals and assumed cold drinks were the culprit. After eliminating iced tea and chilled water from her routine, she noticed mild improvement—but only when she also reduced portion sizes and slowed her eating pace.

Curious, Sophie conducted a self-experiment. Over two weeks, she alternated between drinking cold water and warm herbal tea after identical lunches. She tracked her symptoms using a journal. Surprisingly, her bloating levels were nearly identical regardless of water temperature. The real triggers turned out to be eating too quickly and consuming high-FODMAP foods like onions and garlic.

Her experience underscores a crucial point: attributing digestive discomfort solely to cold water can distract from more impactful factors such as eating habits, food choices, stress levels, and underlying conditions.

When Cold Water Might Actually Help

Contrary to popular warnings, cold water can be beneficial in specific situations. During or after intense physical activity, especially in hot environments, cold water helps regulate core body temperature and rehydrate more effectively than warm fluids. Athletes often prefer cold water because it’s absorbed slightly faster and feels more refreshing.

Additionally, some studies suggest that drinking cold water may temporarily boost metabolism due to the body’s effort to rewarm the liquid—a phenomenon known as water-induced thermogenesis. While the effect is modest (around 5–10 extra calories burned per glass), it adds up subtly over time.

For people with acid reflux, cold water may provide short-term relief by cooling irritated esophageal tissue. Though it doesn’t treat the root cause, it can soothe burning sensations better than warm liquids in acute episodes.

Step-by-Step Guide to Optimizing Post-Meal Hydration

- Assess Your Symptoms: Note whether you experience bloating, cramping, or fullness after meals—and whether it correlates with fluid temperature.

- Experiment Mindfully: Try drinking room-temperature water for three days, then switch to cold water for another three. Keep a log of digestive comfort.

- Monitor Volume: Avoid drinking more than 8–12 ounces of any liquid during or immediately after meals to prevent stomach distension.

- Consider Timing: Wait 20–30 minutes after eating before consuming large amounts of water to allow initial digestion to occur.

- Adjust Based on Climate: In hot weather, cold water may be more hydrating and comfortable; in winter, warm fluids may feel more natural.

- Consult a Professional: If digestive issues persist despite adjustments, seek evaluation for potential conditions like gastroparesis, IBS, or food intolerances.

Expert Insights: Perspectives from Nutrition and Medicine

Nutrition scientists emphasize that hydration quality matters far more than temperature. “The biggest issue isn’t whether water is cold or warm—it’s whether people are drinking enough at all,” says Dr. Marcus Liu, registered dietitian and digestive health educator. “Dehydration slows intestinal transit and can worsen constipation, regardless of water temperature.”

Liu also points out that many cultures consume cold beverages with meals without widespread digestive complaints. “In Japan, people routinely drink chilled green tea with sushi. In Mexico, agua fresca is served ice-cold alongside heavy dishes. If cold water were inherently disruptive, we’d see population-level patterns of dysfunction—but we don’t.”

“The fear of cold water is often disproportionate to the actual risk. Focus on whole-diet patterns, fiber intake, and mindful eating before obsessing over water temperature.” — Dr. Marcus Liu, RD, CDN

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it bad to drink cold water after eating fatty foods?

No, there is no scientific basis for the claim that cold water causes fats to solidify in the stomach. Fats are broken down by bile and lipase in the small intestine at body temperature. The idea that cold water “freezes” fat is a physiological impossibility under normal conditions.

Can cold water cause stomach pain after meals?

For some sensitive individuals, yes—but not due to impaired digestion. Rapid consumption of very cold liquids may trigger gastric spasms or exacerbate existing conditions like achalasia or esophageal hypersensitivity. The discomfort is usually temporary and related to nerve response, not digestive function.

Is warm water better for digestion?

Warm water may feel more soothing and promote relaxation of the gastrointestinal tract, potentially aiding motility in some people. However, there is no conclusive evidence that it enhances nutrient breakdown or absorption compared to cold or room-temperature water in healthy individuals.

Practical Tips for Better Digestive Health

- Stay consistently hydrated throughout the day to prevent dehydration-related sluggish digestion.

- Aim for 25–30 grams of fiber daily from fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains.

- Eat slowly and chew thoroughly to reduce the burden on your digestive system.

- Limit carbonated drinks and excessive caffeine, which can contribute to bloating and acid reflux.

- Manage stress through mindfulness, breathing exercises, or gentle movement—chronic stress negatively impacts gut function.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Cold Water Debate

The belief that drinking cold water after meals harms digestion is largely a myth unsupported by scientific evidence. While traditional systems like Ayurveda offer valuable frameworks for personalized health, their principles should be applied thoughtfully—not dogmatically. The human digestive system is designed to handle a wide range of temperatures, textures, and inputs with remarkable efficiency.

That said, individual experiences vary. If you find that cold water makes you feel bloated or uncomfortable, there’s no harm in switching to room-temperature or warm options. But for most people, choosing cold water comes down to preference, climate, and comfort—not digestive risk.

Instead of fixating on water temperature, focus on foundational habits: balanced meals, adequate fiber, proper hydration, and mindful eating. These factors have a far greater impact on digestive wellness than whether your glass is chilled or tepid.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?