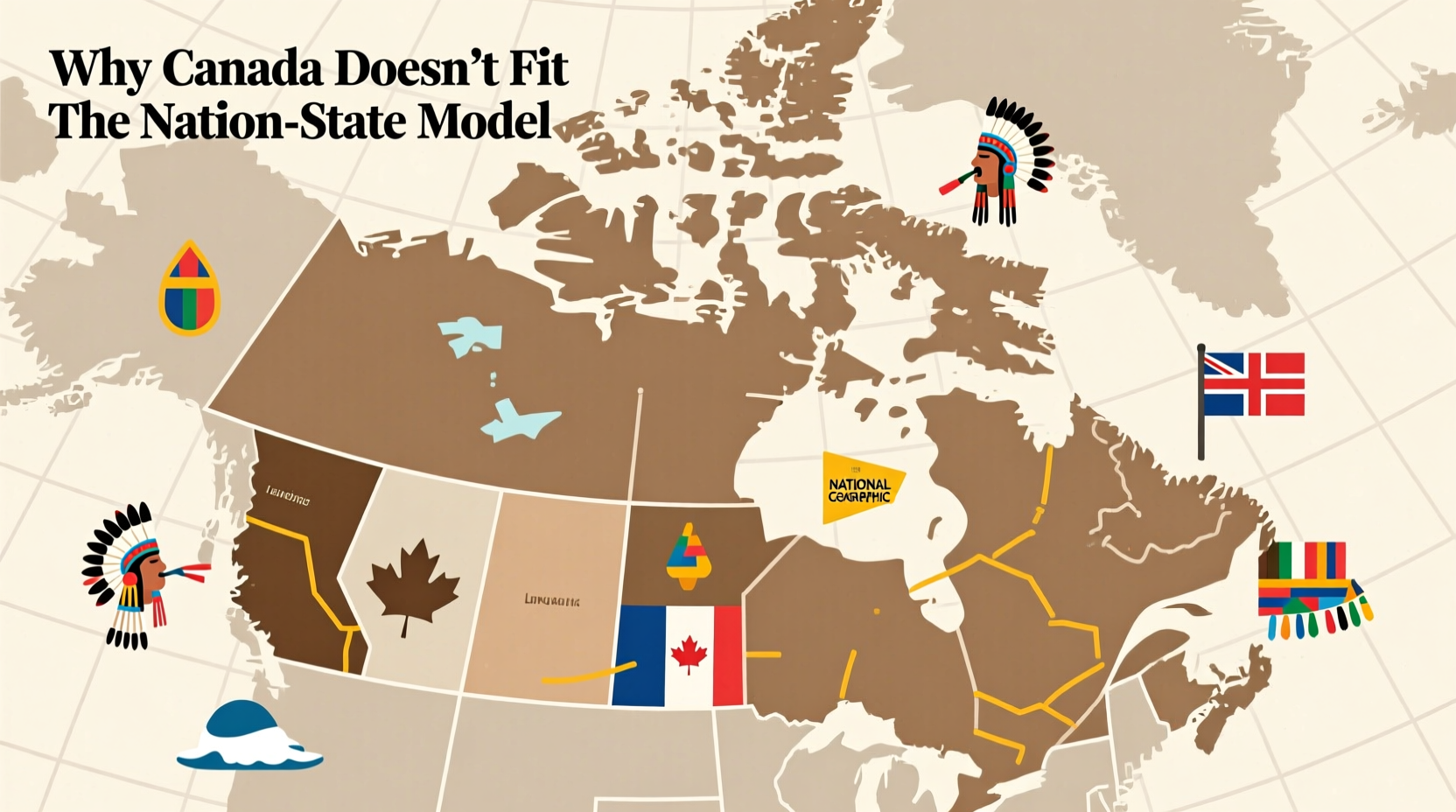

The nation state is a political ideal in which a single, unified nation—defined by shared culture, language, history, or ethnicity—coincides with a sovereign state. This model assumes homogeneity and centralized national identity. Yet, Canada stands as a compelling counterexample. Despite being a stable, recognized sovereign country, Canada diverges from the classic nation state framework in fundamental ways. Its foundation rests not on ethnic or cultural uniformity but on pluralism, asymmetrical federalism, and constitutional recognition of multiple nations within one state.

From its bilingual official structure to the enduring presence of Indigenous self-determination movements, Canada embodies a complex mosaic that resists the simplifying assumptions of the traditional nation state. Understanding these deviations is essential to appreciating Canada’s unique political character and the challenges it navigates in maintaining unity without enforced assimilation.

Linguistic Duality Challenges National Homogeneity

One of the most visible departures from the nation state model is Canada’s official bilingualism. English and French are both recognized as official languages at the federal level, a reflection of the country’s colonial history involving Britain and France. However, this duality is not evenly distributed. Over 75% of French speakers reside in Quebec, where French is the dominant language and central to provincial identity.

Quebec has long pursued policies to protect and promote its Francophone culture, including strict language laws like Bill 101, which mandates French as the language of work, education, and public signage. These efforts stem from a distinct national consciousness that some describe as a “nation within a state.”

This linguistic divide undermines the nation state ideal of a single, unifying national language. Unlike France or Japan—where linguistic uniformity is tightly linked to national identity—Canada institutionalizes difference. The federal government must operate bilingually, and services must be available in both languages, creating administrative complexity uncommon in classical nation states.

Indigenous Peoples and the Plurinational Reality

Perhaps the most profound challenge to the nation state model in Canada lies in the status and aspirations of Indigenous peoples. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities represent distinct nations with their own languages, governance traditions, and historical claims to sovereignty. There are over 630 recognized First Nations across Canada and more than 70 Indigenous languages still spoken today.

The Canadian Constitution Act of 1982 recognizes Aboriginal rights, and Section 35 affirms the existing rights of Indigenous peoples. Landmark court rulings, such as R. v. Sparrow (1990) and Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014), have affirmed Aboriginal title to traditional territories. These legal developments acknowledge that Indigenous nations possess inherent rights that predate the Canadian state itself.

“We are not seeking inclusion in Canada’s project. We are reaffirming our own nationhood.” — Perry Bellegarde, Former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations

This recognition creates a plurinational framework: Canada is not a single nation, but a political entity housing many nations. This contrasts sharply with the Westphalian model of the nation state, which assumes one people, one territory, one government. Instead, Canada increasingly functions as a compound polity where multiple forms of belonging coexist.

Federalism and Regional Asymmetry

Canada’s federal system further distances it from the unitary logic of the nation state. Provinces hold significant constitutional powers, particularly in areas like education, health care, and natural resources. Quebec, in particular, exercises a unique role—opting out of certain federal programs with compensation, maintaining its own immigration selection system, and resisting federal encroachments on cultural jurisdiction.

This asymmetrical federalism allows provinces to act almost as semi-sovereign entities. For example:

- Quebec collects its own income taxes and administers its own pension plan.

- Nunavut operates under a land claims agreement that includes self-governance provisions for Inuit institutions.

- Alberta has recently explored the idea of a “prosperity certificate” to assert economic autonomy.

Such decentralization weakens the idea of a singular national will. Policies in one province may contradict or diverge significantly from those in another, especially on issues like resource development, language, or education. This regional divergence reflects a state built on negotiation and accommodation rather than top-down national integration.

Multiculturalism as State Policy

In 1971, Canada became the first country in the world to adopt multiculturalism as an official policy. This was later enshrined in the Multiculturalism Act of 1988. Rather than promoting assimilation into a dominant national culture, the policy affirms the value of cultural diversity and supports the preservation of heritage languages and traditions.

This approach directly contradicts the nation state ideal, which typically emphasizes cultural cohesion and a shared national narrative. In Canada, citizenship is decoupled from ethnic or cultural conformity. Over 20% of Canadians were born outside the country, and major cities like Toronto and Vancouver are among the most ethnically diverse in the world.

| Nation State Model | Canadian Model |

|---|---|

| Single national identity | Multinational, multicultural identity |

| Assimilation expected | Multiculturalism encouraged |

| Centralized cultural authority | Decentralized, pluralistic norms |

| One official language typical | Two official languages; many unofficial ones |

| Homogeneous citizenry ideal | Diversity as a core value |

While multiculturalism fosters inclusion, it also means there is no singular “Canadian culture” that dominates public life. Instead, national identity is defined procedurally—through adherence to democratic values, rule of law, and Charter rights—rather than culturally.

Case Study: The Quebec Sovereignty Movement

The Quebec independence movement offers a clear illustration of Canada’s imperfect fit with the nation state model. In referendums held in 1980 and 1995, Quebec voters were asked whether the province should seek sovereignty. The first was defeated 60% to 40%. The second came within 58,000 votes of passing, with 49.4% voting “Yes.”

The 1995 referendum revealed deep fissures in the Canadian union. A sovereign Quebec would have constituted a separate nation state based on Francophone identity, while the rest of Canada would continue as a multicultural federation. The federal government responded by passing the Clarity Act in 2000, setting conditions for any future secession vote, including a requirement for a “clear majority” on a “clear question.”

This ongoing tension underscores that Canada exists in a constant state of negotiation. Unity is not assumed but continually reaffirmed through dialogue, concessions, and constitutional accommodations. This dynamic stability is foreign to the static boundaries of the traditional nation state.

Expert Insight: Redefining Nationhood

“Canada is not a nation-state in the European sense. It is a civic state that contains multiple nations. Its legitimacy comes not from ethnic unity but from fairness, inclusion, and consent.” — Dr. Jennifer Smith, Professor of Political Science, Dalhousie University

This perspective highlights a shift from ethnic nationalism to civic nationalism. In Canada, being “Canadian” is less about ancestry and more about shared values: democracy, human rights, and peaceful coexistence. This makes the country resilient in the face of diversity but also perpetually engaged in defining what holds it together.

Checklist: Key Features That Make Canada Atypical as a Nation State

- ✅ Two official languages with unequal geographic distribution

- ✅ Constitutional recognition of Indigenous rights and title

- ✅ Asymmetrical federalism with strong provincial powers

- ✅ Official multiculturalism policy discouraging cultural assimilation

- ✅ Ongoing sovereignty movements in Quebec and Indigenous communities

- ✅ Civic rather than ethnic definition of national identity

- ✅ Decentralized control over education and cultural policy

FAQ

Is Canada a nation state?

No, not in the classical sense. While Canada is a sovereign state, it does not align with the nation state model due to its internal diversity, lack of cultural homogeneity, and recognition of multiple nations within its borders.

Why doesn’t Quebec join France?

Quebec is historically and geographically rooted in North America. Most Quebecers identify as North American and prefer self-governance within or apart from Canada rather than integration into a European nation thousands of miles away. Cultural ties to France are symbolic, not political.

Can a country be stable without being a nation state?

Yes. Canada demonstrates that political stability can emerge from negotiated unity, constitutional protections, and inclusive institutions rather than ethnic or cultural uniformity. Other examples include Switzerland and Belgium.

Conclusion: Embracing Complexity

Canada’s deviation from the nation state model is not a flaw—it is a feature. In a world where rigid national identities often fuel division, Canada offers an alternative: a state grounded in pluralism, consent, and shared institutions rather than mythologized homogeneity. Its challenges—sovereignty debates, Indigenous reconciliation, linguistic balance—are not signs of weakness but evidence of a living, evolving political project.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?