The concept of a carbon tax has gained increasing attention in global policy discussions as nations seek effective tools to combat climate change. At its core, a carbon tax is a fee imposed on the burning of carbon-based fuels—such as coal, oil, and gas—designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by making polluters pay for the environmental cost of their actions. While often debated, the rationale behind implementing a carbon tax is rooted in economics, environmental science, and long-term societal well-being.

Why Governments Impose a Carbon Tax

Greenhouse gas emissions, primarily carbon dioxide (CO₂), are a leading cause of global warming. These emissions result from human activities like transportation, electricity generation, and industrial processes. Unlike traditional pollutants, CO₂ spreads globally and remains in the atmosphere for decades, creating long-term climate risks. Because the true cost of these emissions isn’t reflected in market prices, businesses and consumers have little financial incentive to reduce their carbon footprint.

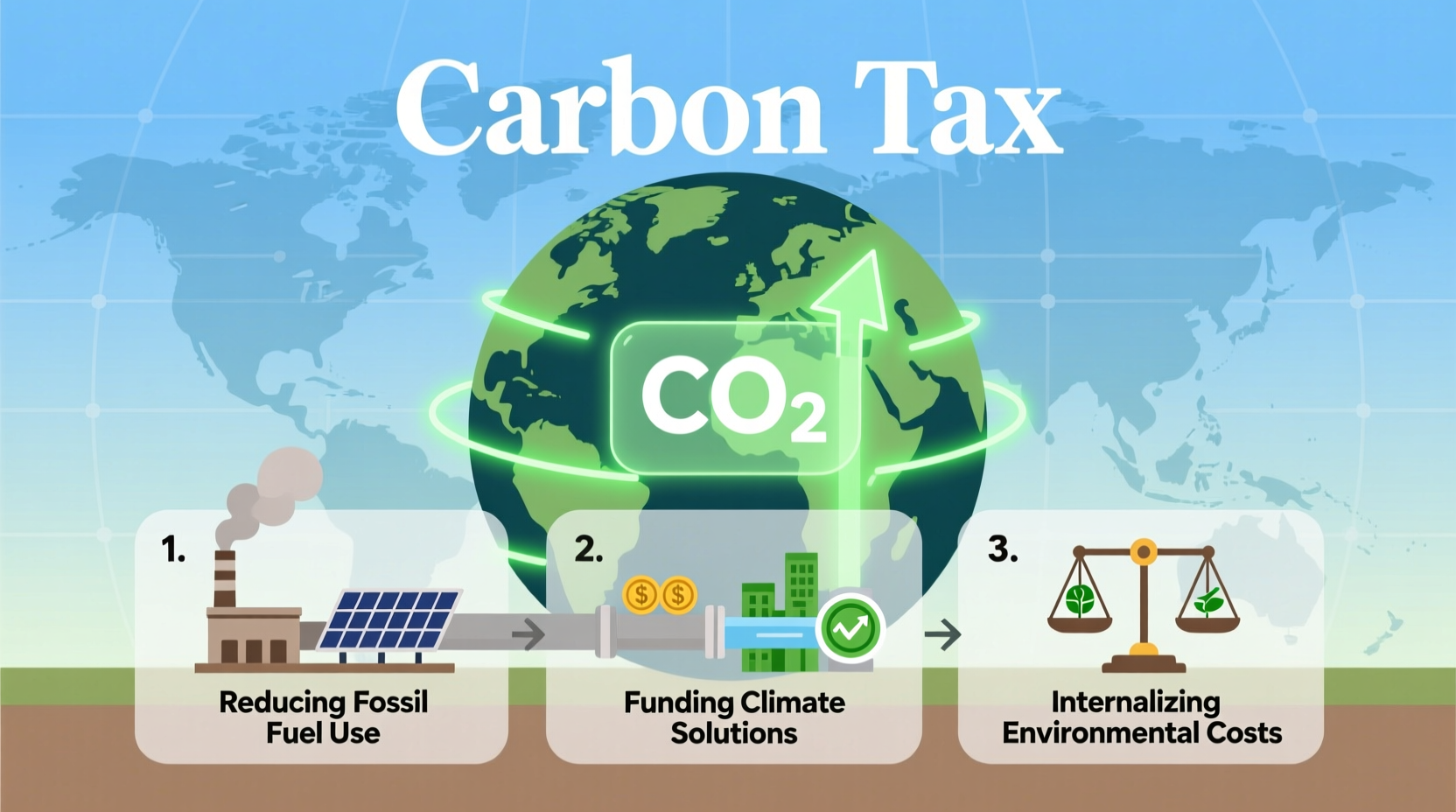

This disconnect is known as a \"market failure.\" A carbon tax corrects this by internalizing the external costs—the damage caused by climate change—that are otherwise borne by society at large. By putting a price on carbon, governments create a direct economic signal: the more you pollute, the more you pay. This encourages innovation, energy efficiency, and a shift toward cleaner alternatives.

How a Carbon Tax Influences Behavior

A carbon tax works through price incentives. When fossil fuels become more expensive due to taxation, individuals and businesses naturally seek lower-cost, cleaner alternatives. For example:

- Manufacturers may invest in energy-efficient machinery.

- Households might switch to electric heating or improve home insulation.

- Automakers accelerate development of electric vehicles.

- Utilities increase investment in wind, solar, and other renewable sources.

Over time, these individual choices compound into systemic change. Economists refer to this as creating a “price signal” that guides markets toward sustainability without heavy-handed regulation.

Sweden offers a compelling real-world example. In 1991, the country introduced a carbon tax starting at $27 per ton. Today, it exceeds $130 per ton—the highest in the world. During this period, Sweden’s GDP grew by over 75%, while emissions dropped by more than 30%. This demonstrates that a strong carbon price can drive emission reductions without sacrificing economic growth.

“We need to make sure that the prices people pay for energy reflect the true social cost of carbon. That’s where a carbon tax becomes essential.” — Dr. William Nordhaus, Nobel Laureate in Economics

Comparing Policy Approaches: Carbon Tax vs. Cap-and-Trade

While carbon taxes are one method of pricing carbon, another common approach is cap-and-trade. Understanding the differences helps clarify why some governments prefer one over the other.

| Feature | Carbon Tax | Cap-and-Trade |

|---|---|---|

| Price Certainty | Yes – tax rate is set and predictable | No – prices fluctuate based on market demand |

| Emission Certainty | No – total emissions depend on response to price | Yes – emissions capped by law |

| Administrative Simplicity | High – integrates with existing tax systems | Lower – requires monitoring, trading platforms |

| Revenue Generation | Yes – direct government income | Only if permits are auctioned |

| Business Planning | Easier due to price predictability | More complex due to price volatility |

Carbon taxes offer transparency and simplicity, making them easier to administer and communicate. Cap-and-trade systems guarantee emission reductions but can suffer from price volatility and market manipulation. Many experts argue that a well-designed carbon tax provides a more stable foundation for long-term planning and innovation.

Addressing Equity and Social Impact

One major concern about carbon taxes is their potential regressive impact—low-income households spend a higher proportion of their income on energy and transportation, so rising fuel and utility costs could disproportionately affect them.

To address this, many jurisdictions design their carbon tax policies with equity in mind. For instance:

- British Columbia returns all carbon tax revenue through rebates and tax cuts, with a special low-income credit.

- In Canada, the federal carbon pricing system sends most proceeds directly back to households via annual Climate Action Incentive payments.

- Some proposals advocate using revenues to fund public transit, energy efficiency upgrades in low-income housing, or job training in clean energy sectors.

These mechanisms ensure that while the tax raises the cost of pollution, it doesn’t unfairly burden those who can least afford it. Done right, a carbon tax can be both environmentally effective and socially just.

Step-by-Step: How a National Carbon Tax Is Implemented

Rolling out a carbon tax involves careful planning and phased execution. Here’s a realistic timeline and process:

- Assessment (Months 1–6): Analyze current emissions by sector, identify major sources, and model economic impacts.

- Policy Design (Months 6–12): Set initial tax rate, define coverage (e.g., fuels, industries), and decide on revenue use.

- Stakeholder Engagement (Ongoing): Consult with industry, environmental groups, and communities to build consensus.

- Legislation & Launch (Year 1): Pass enabling laws, establish collection mechanisms through fuel distributors or importers.

- Phased Increase (Years 2–10): Gradually raise the tax rate to give businesses time to adapt (e.g., $20/ton starting, rising by $10/year).

- Monitoring & Adjustment (Ongoing): Track emissions, economic indicators, and public feedback; adjust policy as needed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does a carbon tax actually reduce emissions?

Yes. Empirical evidence from countries like Sweden, Norway, and British Columbia shows measurable declines in emissions following the introduction of carbon pricing. The key is setting a price high enough to change behavior—most experts recommend $50–$100 per ton of CO₂ for meaningful impact.

Can a carbon tax hurt the economy?

Not necessarily. Studies show that when revenue is recycled wisely—through tax reductions, investments, or rebates—economic growth can continue. In fact, directing funds toward innovation and infrastructure can stimulate new industries and jobs in clean energy sectors.

What’s the difference between a carbon tax and a fuel tax?

A fuel tax applies broadly to gasoline or diesel, often funding transportation infrastructure. A carbon tax specifically targets the carbon content of all fossil fuels (including coal and natural gas) and is designed to reduce emissions, not just generate revenue.

Actionable Checklist for Policymakers and Citizens

Whether you're involved in policy or simply want to understand your role, here’s what you can do:

- ✅ Support transparent carbon pricing legislation that includes accountability measures.

- ✅ Advocate for equitable revenue use, such as household rebates or green infrastructure.

- ✅ Encourage your business or organization to measure and reduce its carbon footprint.

- ✅ Stay informed about local and national carbon pricing initiatives.

- ✅ Reduce personal carbon use by choosing public transit, energy-efficient appliances, or renewable energy options.

Conclusion: A Necessary Step Toward a Sustainable Future

Understanding the reasons behind a carbon tax reveals its role not as a punitive measure, but as a pragmatic solution to a global challenge. It aligns economic incentives with environmental responsibility, empowering markets to innovate and individuals to make greener choices. While no single policy can solve climate change alone, a well-designed carbon tax is one of the most effective tools available.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?