Allspice, known botanically as Pimenta dioica, is a single spice that delivers the complex illusion of a blend—reminiscent of cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and pepper. This aromatic profile isn't accidental; it results from a precise combination of volatile organic compounds naturally present in the dried berry of the allspice tree. Understanding these chemical components reveals not only why allspice tastes and smells the way it does but also how it functions in cooking, preservation, and even traditional medicine. For chefs, home cooks, and food scientists alike, knowing what makes allspice work at a molecular level empowers better seasoning decisions, smarter substitutions, and deeper appreciation for one of the Caribbean’s most iconic exports.

Definition & Overview

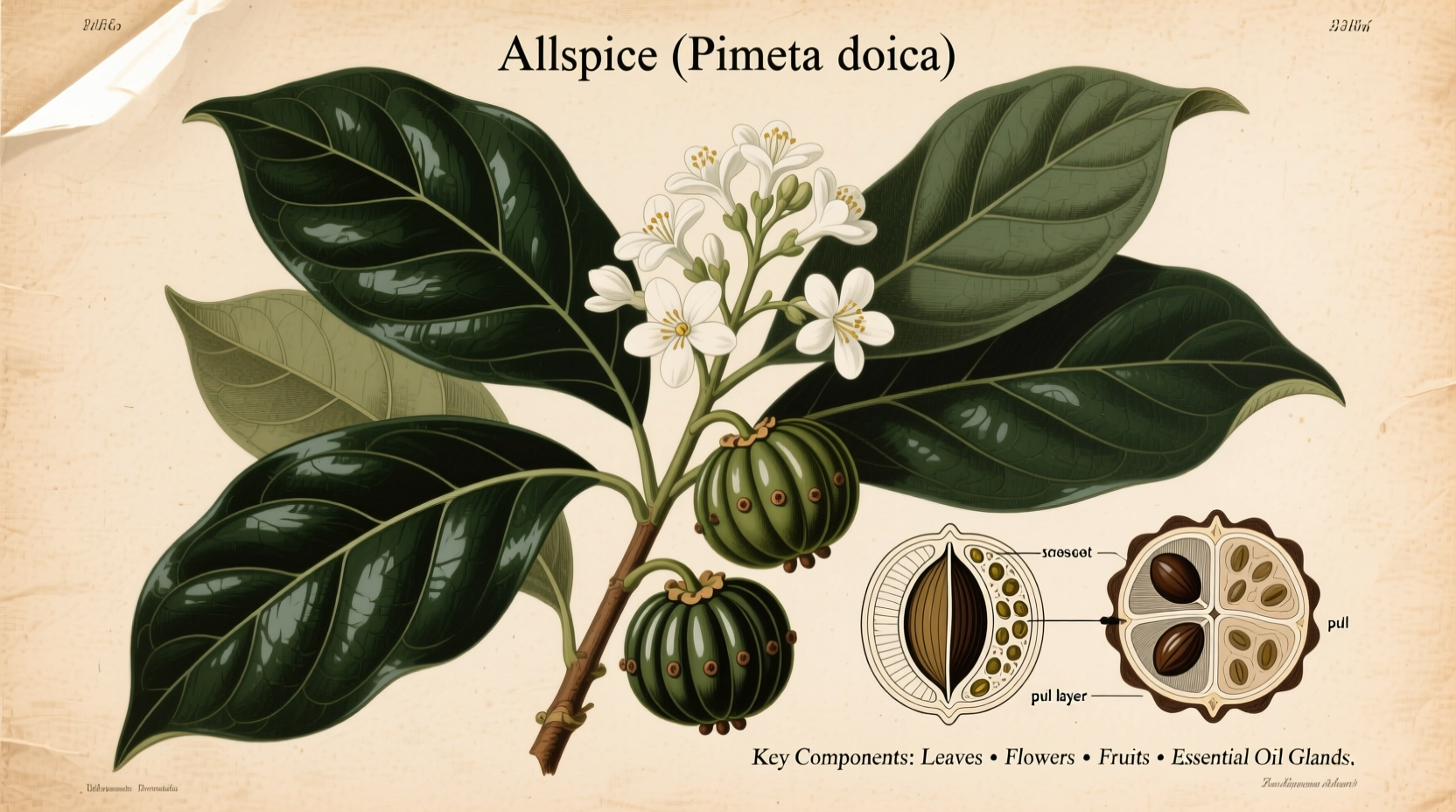

Allspice is the dried unripe berry of an evergreen tree native to the Greater Antilles, southern Mexico, and Central America, with Jamaica remaining the most renowned producer. Despite its name, it is not a mixture of spices but a singular ingredient whose aroma evokes a blend—hence “allspice.” Historically, Spanish explorers in the 15th century likened its scent to a fusion of familiar European spices, leading to its English name. The whole berries are small, dark brown, and peppercorn-like, while the ground form is a fine reddish-brown powder commonly used in marinades, stews, baked goods, and pickling brines.

Culinarily, allspice bridges sweet and savory applications. It plays a central role in Jamaican jerk seasoning, Middle Eastern baharat, American pumpkin pie spice blends, and Scandinavian meat dishes. Its versatility stems from the synergy of its chemical constituents, each contributing distinct sensory and functional properties.

Key Characteristics of Allspice

The unique sensory impact of allspice arises from a suite of bioactive compounds concentrated in the essential oil of the berry. These compounds define its flavor, aroma, stability, and interaction with other ingredients. Below is a breakdown of the primary components and their contributions:

| Compound | Chemical Class | Concentration in Allspice (approx.) | Sensory Contribution | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eugenol | Phenylpropanoid | 60–90% | Clove-like, warm, slightly medicinal | Antimicrobial, antioxidant, analgesic |

| Caryophyllene (β-caryophyllene) | Sesquiterpene | 5–15% | Peppery, woody, spicy | Anti-inflammatory, binds to CB2 receptors |

| Terpinene (α- and γ-) | Monoterpene | 1–5% | Fresh, citrusy, pine-like notes | Volatile carrier, enhances aroma diffusion |

| Limonene | Monoterpene | 1–4% | Citrusy, uplifting top note | Antioxidant, improves oil solubility |

| Methyl eugenol | Phenylpropanoid derivative | Trace–3% | Sweet, floral, clove-adjacent | Controversial; regulated in high doses |

| Chavicol | Phenolic ether | Trace–2% | Sharp, herbal, anise-like | Antifungal, supports preservation |

These compounds do not act in isolation. Their interactions create a layered aroma profile that unfolds during cooking—top notes of citrus and pine, a warm clove-like core, and a lingering peppery finish. This complexity allows allspice to integrate seamlessly into diverse dishes without dominating when used judiciously.

How Chemical Components Influence Flavor and Aroma

The dominance of **eugenol**—also the primary compound in cloves—is responsible for the pronounced warmth and slight numbing sensation associated with allspice. At concentrations above 70%, eugenol provides antimicrobial effects useful in preserving meats and pickles, a function historically exploited in Caribbean curing traditions. However, its potency means overuse can lead to bitterness or anesthetic mouthfeel, particularly in delicate desserts.

β-Caryophyllene adds structural depth. As a sesquiterpene, it is less volatile than monoterpenes, meaning it releases slowly during prolonged cooking—ideal for braises, stews, and slow-roasted meats. Notably, β-caryophyllene is a dietary cannabinoid that selectively activates the CB2 receptor, linked to anti-inflammatory responses, making allspice of interest in functional food research.

The minor terpenes—**limonene**, **terpinene**, and **pinene**—contribute freshness and lift, preventing the spice from tasting heavy or cloying. These compounds are highly volatile and dissipate quickly when exposed to heat or air, which explains why freshly ground allspice has a brighter aroma than pre-ground versions stored for months.

Methyl eugenol, while aromatic, is subject to regulatory scrutiny due to potential carcinogenicity in extremely high doses (far beyond culinary use). Reputable spice suppliers monitor levels, and typical culinary consumption poses no risk. Still, moderation is advised, especially in homemade extracts or infusions.

Practical Usage in Cooking

The chemical makeup of allspice directly informs how it should be used in the kitchen. Because its key compounds vary in volatility and solubility, technique matters.

- Whole vs. Ground: Whole berries retain essential oils longer and are ideal for slow-cooked dishes like pot roasts, soups, or mulled wine. They release eugenol and caryophyllene gradually. Ground allspice disperses flavor quickly but loses aroma within 6–12 months; use it in baking or quick sautés.

- Heat Application: Add ground allspice early in dry-toasting or oil-sautéing to volatilize terpenes and mellow eugenol’s sharpness. In baking, combine with fats (butter, oil) to improve solubility of non-polar compounds like caryophyllene.

- Pairings: Combine with ingredients that complement or contrast its profile:

- Dairy and fat: Cream, butter, and coconut milk carry its lipophilic compounds, enhancing mouthfeel and flavor release.

- Acidic elements: Citrus zest, vinegar, or tomatoes brighten its top notes and balance warmth.

- Sweet bases: Brown sugar, molasses, and honey amplify its clove-cinnamon illusion in pies and glazes.

- Proteins: Especially effective with pork, lamb, game meats, and legumes, where its antimicrobial properties may aid digestion.

Tip: Bloom whole allspice berries in warm oil with onions and garlic at the start of a stew or curry. This extracts caryophyllene and eugenol into the fat, distributing flavor more evenly than adding ground spice later.

Classic Applications by Cuisine

- Jamaican Jerk Chicken: Allspice (whole and ground) is the backbone of the marinade, combined with Scotch bonnet peppers, thyme, and green onions. Slow grilling over pimento wood (from the same tree) intensifies the eugenol-caryophyllene synergy.

- Swedish Meatballs: A pinch of ground allspice with nutmeg and white pepper adds warmth without heat, balancing creamy gravy.

- Pumpkin Pie: Allspice contributes to the “pumpkin spice” illusion, working with cinnamon and ginger. Use sparingly—¼ tsp per pie—to avoid clove dominance.

- Beef Patties (Caribbean): Incorporated into spiced ground beef fillings, where its preservative qualities may have historically helped extend shelf life in tropical climates.

- Pickling Spices: Whole allspice berries appear in brines for cucumbers, onions, and eggs, leveraging eugenol’s antimicrobial action and pleasant aroma.

Variants & Types of Allspice

While allspice refers specifically to Pimenta dioica, it comes in forms that affect how its components are delivered:

- Whole Berries: Best for long-term storage and controlled infusion. Ideal for stocks, poaching liquids, and pickling. Crush lightly before use to increase surface area.

- Ground Allspice: Convenient for baking and rubs. Loses potency faster; store in airtight, opaque containers away from heat.

- Allspice Essential Oil: Highly concentrated (up to 90% eugenol). Used in aromatherapy and flavoring, but not for direct culinary use without dilution. One drop equals ~½ tsp ground spice.

- Pimento Leaves: Less common but used in Jamaica for wrapping foods or making tea. Contain lower eugenol but similar aromatic profiles.

- Smoked Allspice: A specialty product, dried over pimento wood fires, adding phenolic smokiness that complements grilled meats.

No true “substitute” replicates allspice’s full chemical profile, but blends attempt approximation (see below).

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Allspice is frequently mistaken for a blend or confused with individual spices it resembles. The table below clarifies key differences:

| Ingredient | Primary Compounds | Flavor Profile | Key Difference from Allspice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloves | Eugenol (80–90%) | Intense, medicinal, numbing | Lacks caryophyllene’s pepperiness and terpene brightness; more aggressive |

| Cinnamon (Ceylon) | Eugenol (trace), cinnamaldehyde (60–80%) | Sweet, woody, aldehyde-sharp | No peppery base; dominated by cinnamaldehyde, not eugenol |

| Nutmeg | Myristicin, elemicin, safrole | Warm, nutty, mildly hallucinogenic in excess | Psychoactive compounds absent in allspice; lacks clove-like punch |

| Black Pepper | Piperine (5–9%) | Pungent, sharp, heat-building | Heat from piperine is tactile (burns); allspice warmth is aromatic |

| Pumpkin Spice Blend | Mixture: cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, allspice, cloves | Balanced sweet-warm | Allspice is one component of this blend, not the whole |

A common myth is that allspice is a mix of cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg. While these spices share some overlapping compounds (e.g., trace eugenol in cinnamon), none replicate the balanced ratio found in genuine allspice berries.

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I substitute allspice?

Yes, but imperfectly. A common workaround is mixing ½ tsp ground cloves + ¼ tsp cinnamon + ¼ tsp nutmeg to approximate 1 tsp allspice. However, this lacks caryophyllene’s peppery nuance and may taste overly sweet or clove-heavy. For savory dishes, add a pinch of black pepper to mimic complexity.

How should I store allspice?

Keep whole berries in a cool, dark place in an airtight glass jar—they retain potency for 3–4 years. Ground allspice lasts 6–12 months. Avoid plastic containers, which can absorb essential oils and degrade terpenes.

Is allspice safe in large amounts?

In culinary quantities, yes. Eugenol in excess (e.g., undiluted essential oil) can cause liver toxicity or act as a blood thinner. Stick to recipes using ≤1 tsp ground allspice per serving. Pregnant individuals should consult a physician before consuming medicinally.

Why does my allspice taste bitter?

Bitterness often results from old or improperly stored spice. Oxidized eugenol degrades into quinones, which taste harsh. Toasting stale allspice can worsen this. Always check aroma: fresh allspice should smell warmly sweet, not musty or flat.

Does allspice contain actual pepper?

No. The “pepper” note comes from β-caryophyllene, not piperine. Botanically, allspice is unrelated to black pepper (Piper nigrum), though both were historically grouped as “hot” spices in European apothecaries.

Expert Insight: “Allspice is nature’s perfect blend. Its chemistry evolved not for our palates but as a defense mechanism. We’re lucky that protection tastes so good.” — Dr. Lena Cho, Food Biochemist, UC Davis

Summary & Key Takeaways

Allspice owes its distinctive flavor and utility to a natural cocktail of chemical compounds, chief among them eugenol, β-caryophyllene, and supporting terpenes. These components work in concert to deliver a warm, clove-like aroma with peppery depth and citrusy lift—explaining its irreplaceable role across global cuisines.

- Eugenol dominates the profile, providing clove-like warmth and antimicrobial benefits.

- β-Caryophyllene adds a peppery, woody backbone and offers emerging health interest due to its interaction with endocannabinoid receptors.

- Minor terpenes (limonene, terpinene) contribute freshness but are vulnerable to oxidation—favor fresh grinding for best results.

- Whole berries outperform ground spice in long-cooked dishes; ground form suits baking and quick applications.

- No spice blend fully replicates authentic allspice, though combinations of clove, cinnamon, and nutmeg offer rough approximations.

- Proper storage preserves volatile compounds; keep away from light, heat, and moisture.

Understanding the science behind allspice transforms it from a pantry staple into a precision tool. Whether you're balancing a stew, crafting a holiday spice mix, or exploring the biochemistry of flavor, recognizing its components allows for greater control, creativity, and respect for this remarkable berry.

Explore your spice cabinet with new insight—what seems simple often holds the most complexity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?