In everyday conversation, we use common names to refer to plants, animals, chemicals, and diseases. These names—like “killer whale,” “vitamin B complex,” or “pink mold”—are easy to remember and widely understood. But in scientific contexts, they often cause confusion, miscommunication, and even errors in research and policy. While convenient, common names lack precision, vary across regions, and may obscure critical biological or chemical distinctions. This article explores why relying on common names in science is problematic and how standardized nomenclature offers a more reliable alternative.

The Ambiguity of Common Names

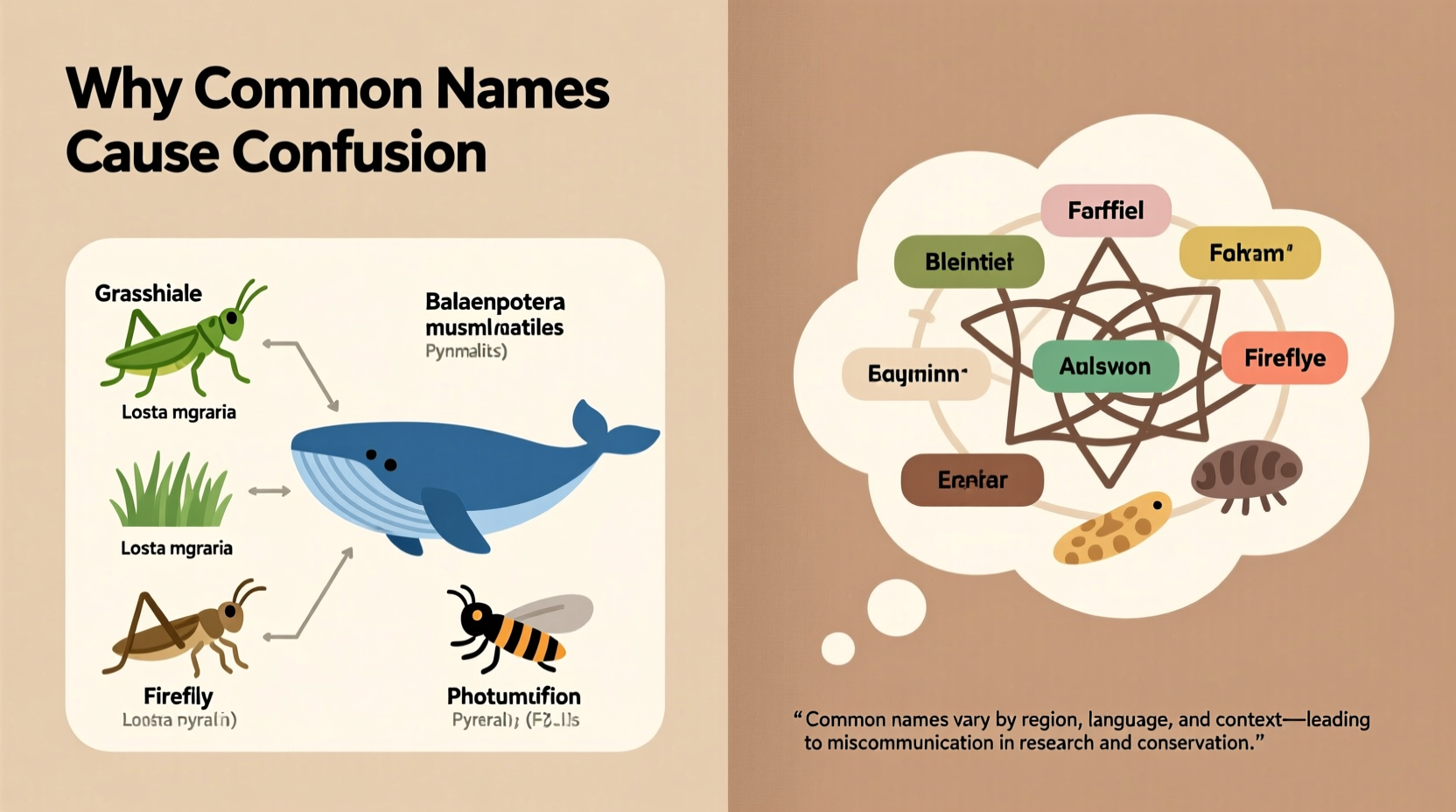

One of the most significant issues with common names is their inherent ambiguity. A single name can refer to multiple species, substances, or conditions depending on context, geography, or language. For example, the term “dolphin” commonly refers to oceanic dolphins (family Delphinidae), but it’s also used for river dolphins, which are biologically distinct and belong to different families. Similarly, “jellyfish” isn’t a taxonomic category at all—it includes creatures from several unrelated phyla, such as cnidarians and ctenophores.

This imprecision becomes dangerous when decisions about conservation, medicine, or food safety depend on accurate identification. If a fish labeled “snapper” in a market turns out to be a different species due to regional naming practices, consumers may unknowingly ingest a toxic substitute or contribute to overfishing of endangered species.

Variability Across Regions and Languages

Common names differ dramatically between countries and cultures. What Americans call a “rooster,” British English speakers refer to as a “cock.” The animal known as a “cougar” in North America is called a “puma” or “mountain lion” elsewhere. In Australia, “jelly blubber” refers to a specific type of jellyfish, while in the Caribbean, similar terms might describe entirely different marine organisms.

Linguistic variation compounds the problem. The same plant may have dozens of local names across Latin America, making it difficult for researchers to compile data or assess medicinal uses without cross-referencing each variant. Without a universal standard, collaboration across borders becomes inefficient and error-prone.

“Common names are useful for public engagement, but they fail when precision is required. Scientific nomenclature exists precisely to eliminate this kind of ambiguity.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Taxonomist at the Royal Botanic Gardens

Misleading Implications and Public Misunderstanding

Many common names carry emotional or misleading connotations that distort public perception. Take the “killer whale,” for instance—a highly intelligent, social animal misrepresented by a name that suggests aggression and danger. Despite being responsible for no recorded unprovoked attacks on humans in the wild, the label contributes to fear-based policies and captivity debates.

Likewise, the term “pink mold” sounds alarming, but it often refers not to true mold (fungi) but to Serratia marcescens, a bacterium that thrives in damp environments. Calling it “mold” leads people to use antifungal cleaners instead of antibacterial agents, reducing effectiveness and prolonging contamination.

These misnomers affect health decisions, environmental attitudes, and funding priorities. A disease named “flesh-eating bacteria” generates panic disproportionate to actual risk, potentially diverting resources from more widespread but less sensational illnesses.

Scientific Nomenclature as the Solution

To address these problems, scientists rely on standardized naming systems. In biology, the binomial nomenclature introduced by Carl Linnaeus assigns each species a two-part Latinized name—genus and species—such as Homo sapiens or Quercus alba. This system ensures global consistency regardless of language or region.

Similarly, chemistry uses IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) nomenclature to name compounds unambiguously. Instead of calling a substance “laughing gas,” scientists use “dinitrogen monoxide” (N₂O), eliminating confusion with other gases like nitric oxide (NO) or nitrogen dioxide (NO₂).

Medical classifications follow systems like the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), ensuring that “diabetes mellitus type 2” means the same thing in Tokyo, Toronto, and Tunis.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Problem with Common Name |

|---|---|---|

| Prairie dog | Cynomys ludovicianus | Not a dog; a burrowing rodent |

| Starfish | Asterias rubens | No relation to fish; an echinoderm |

| Vitamin B complex | Mixture of B₁, B₂, B₃, etc. | Vague; combines eight chemically distinct vitamins |

| Tomato hornworm | Manduca quinquemaculata | Easily confused with Manduca sexta, a closely related pest |

Real-World Consequences: A Case Study

In 2013, a seafood fraud investigation by Oceana revealed that nearly one-third of fish sold in U.S. markets were mislabeled. Red snapper, a high-value fish, was frequently substituted with cheaper look-alikes such as rockfish or tilapia. Because both sellers and consumers relied on the common name rather than the scientific designation Lutjanus campechanus, deception went undetected for years.

The consequences extended beyond consumer fraud. Overfishing of true red snapper continued unchecked because catch reporting used inconsistent naming conventions. Conservation efforts faltered due to inaccurate population assessments. Only after implementing DNA barcoding and requiring scientific names in fisheries reporting did management strategies improve.

This case underscores how reliance on common names can undermine sustainability, economic fairness, and scientific integrity—even in regulated industries.

Best Practices for Using Common Names Responsibly

Abandoning common names entirely isn’t practical. They play a vital role in education, outreach, and accessibility. However, their use should be guided by best practices to minimize risk.

- Always pair common names with scientific names upon first mention in technical writing.

- Use authoritative databases like ITIS (Integrated Taxonomic Information System) or NCBI to verify correct nomenclature.

- Be transparent about regional variations when communicating internationally.

- Avoid emotionally charged or sensational terms in public communication unless clearly contextualized.

- Train students and professionals to recognize the limitations of vernacular terminology.

FAQ

Why do scientists still allow common names if they’re so problematic?

Common names are essential for public engagement, informal discussion, and early education. The goal isn’t elimination but responsible use—supplementing them with precise terminology when clarity is critical.

Can a species have more than one valid scientific name?

Occasionally, yes—due to historical classification changes or taxonomic debate. However, authoritative bodies like the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) work to standardize usage and resolve synonyms.

Are there official lists of approved common names?

Some organizations maintain standardized common names—for example, the American Ornithological Society publishes a checklist of accepted bird names. But these are recommendations, not universally enforced standards.

Actionable Checklist: Ensuring Clarity in Science Communication

- Identify whether your audience requires precision (e.g., researchers vs. general public).

- If using a common name, provide the scientific name in parentheses the first time it appears.

- Verify names against authoritative sources (ITIS, IUCN, NCBI, IUPAC).

- Clarify geographic or cultural context if discussing regional terms.

- Avoid metaphors or dramatized labels (e.g., “superbug,” “killer algae”) in formal contexts.

- Encourage peer reviewers or editors to flag ambiguous naming.

Conclusion

Common names serve a purpose—they make science accessible and relatable. But when accuracy, safety, or reproducibility is at stake, they fall short. From misidentified species to misunderstood diseases, the cost of linguistic convenience can be high. By embracing standardized nomenclature and using common names thoughtfully, scientists, educators, and communicators can bridge the gap between clarity and connection.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?