Onions are a cornerstone of global cuisine, forming the aromatic base of countless dishes from soups and stews to salsas and roasts. Yet not all onions are interchangeable. Among the most commonly confused varieties are sweet onions and yellow onions—two alliums that look similar at first glance but diverge significantly in flavor, texture, and culinary application. Understanding these differences is essential for achieving balanced taste and optimal results in both everyday cooking and refined preparations. Choosing the wrong onion can turn a delicate sauce cloyingly sharp or leave a raw salad harsh and pungent. This guide breaks down the distinctions with precision, offering practical insight into when and how to use each variety effectively.

Definition & Overview

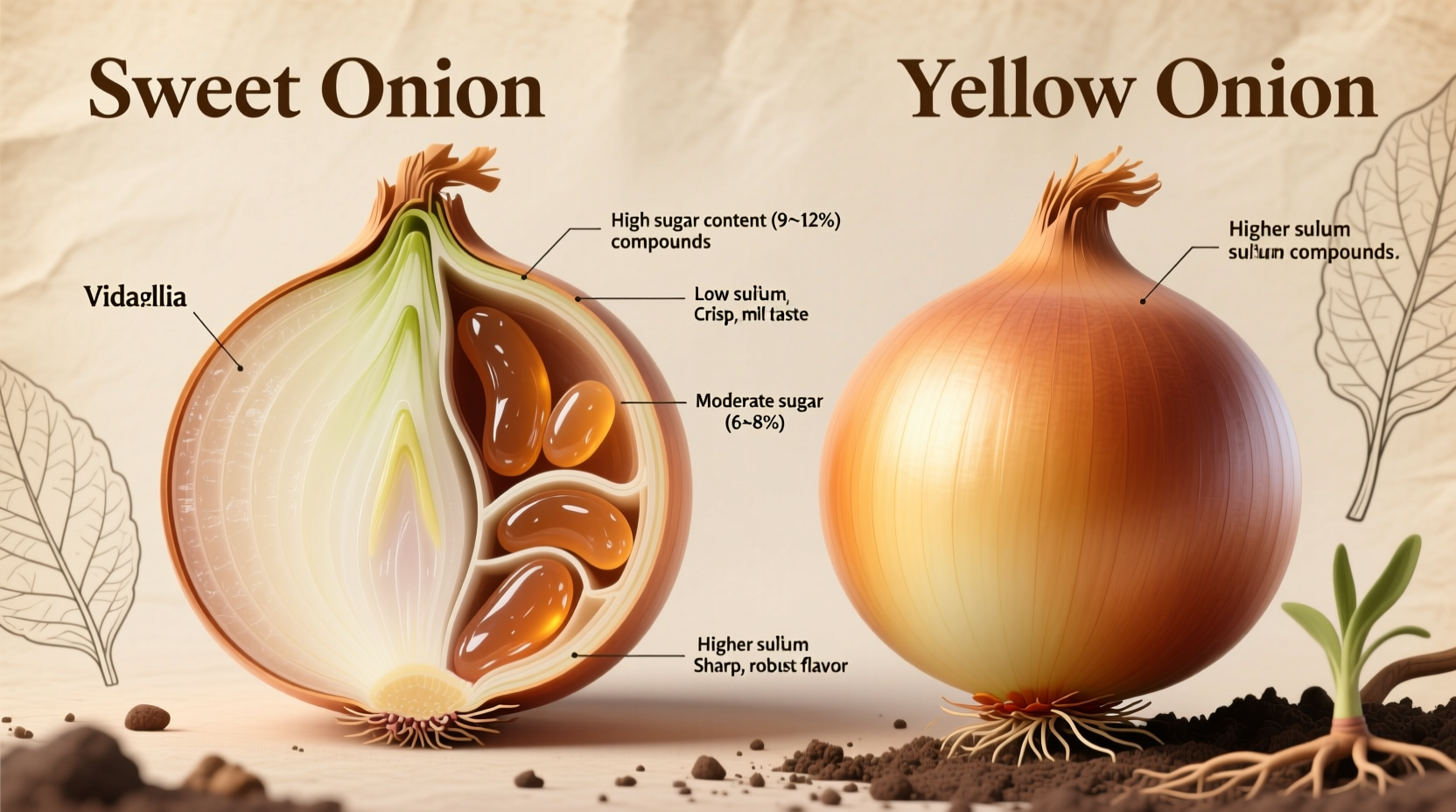

Yellow onions, also known as brown onions due to their papery outer skin, are the workhorse of the onion family. They belong to the *Allium cepa* species and are characterized by their firm texture, strong aroma, and high sulfur content. When raw, they deliver a sharp, assertive bite; when cooked, they undergo a transformation, mellowing into a rich, savory-sweet complexity that forms the backbone of countless savory dishes.

Sweet onions, on the other hand, are a cultivated subgroup of yellow onions bred specifically for lower pyruvic acid and sulfur levels, resulting in a naturally milder, sweeter profile. Varieties such as Vidalia (from Georgia), Walla Walla (from Washington), and Maui (from Hawaii) are legally protected by geographic origin and regulated growing conditions. Their seasonality—typically late winter through early summer—adds to their premium status in fresh markets.

While both types share visual similarities and are used across cuisines, their biochemical makeup leads to divergent behaviors in the kitchen. Recognizing these differences empowers cooks to make informed decisions that elevate dish outcomes.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Yellow Onion | Sweet Onion |

|---|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Sharp, pungent when raw; develops deep umami and caramelized sweetness when cooked | Mild, subtly sweet even when raw; less depth when cooked, prone to over-browning |

| Aroma | Strong, eye-watering when cut due to high sulfur compounds | Gentle, faintly floral; minimal eye irritation |

| Color & Form | Tan-to-brown skin, off-white to pale yellow flesh, round and compact | Pale golden skin, very white flesh, often larger and flatter than yellow onions |

| Moisture Content | Moderate (75–80%) | High (up to 90%), contributing to juiciness and shorter shelf life |

| Shelf Life | 3–4 months in cool, dry storage | 2–4 weeks; best refrigerated after opening or if not used immediately |

| Culinary Function | Aromatic base, long-cooked foundations, flavor layering | Raw applications, quick sautés, garnishes, grilling |

| Best Season | Year-round availability | Late winter to early summer (March–August depending on region) |

Practical Usage: How to Use Each Onion Type

When to Use Yellow Onions

Yellow onions are ideal for any recipe requiring prolonged cooking or foundational flavor development. Their high sulfur content breaks down during heat exposure, producing complex Maillard reaction products that enrich sauces, braises, and stocks.

- Sautéing and Sweating: Begin most savory dishes—curries, ragus, stir-fries, and casseroles—with diced yellow onions cooked in fat over medium-low heat until translucent. This builds a savory base without overwhelming sweetness.

- Caramelization: Cook sliced yellow onions slowly (30–45 minutes) in butter or oil until deeply golden. The natural sugars concentrate, creating a jam-like condiment perfect for burgers, tarts, or cheese boards.

- Stocks and Broths: Add quartered yellow onions (skin-on for color) to bone broths and vegetable stocks. Their robust flavor extracts fully during long simmering.

- Roasting: Toss wedges with olive oil, salt, and herbs. Roast at 400°F (200°C) for 30–40 minutes until tender and slightly charred. They pair well with meats and root vegetables.

When to Use Sweet Onions

Sweet onions shine where their delicate flavor won’t be lost or degraded by heat. Their low sulfur content makes them palatable raw and suitable for dishes where balance and freshness are key.

- Raw Applications: Slice thinly for salads, sandwiches, tacos, or ceviche. Their crisp texture and mild sweetness enhance rather than dominate.

- Grilled or Charred: Cut into thick rounds, brush with oil, and grill over medium heat. The high moisture content steams the interior while the exterior chars lightly. Serve as a side or burger topping.

- Quick Sauté: Cook briefly (5–7 minutes) to retain sweetness without browning excessively. Ideal for omelets, fajitas, or relishes.

- Onion Rings: Due to size and sweetness, sweet onions like Vidalias make superior onion rings. Batter adheres well, and the mild flavor prevents post-fry bitterness.

Pro Tip: Never substitute sweet onions one-to-one for yellow onions in long-cooked dishes unless you adjust technique. Their high water content prolongs cooking time, and they can burn before fully softening. If using sweet onions in place of yellow, increase cooking time slightly and monitor closely to prevent scorching.

Variants & Types

Common Sweet Onion Cultivars

Sweet onions are not a single variety but a category defined by low pungency and geographic terroir. Key types include:

- Vidalia (Georgia): Grown in low-sulfur soil, this onion has a honeyed sweetness and crisp texture. Protected under U.S. federal marketing order—only onions grown in designated counties of Georgia may bear the name.

- Walla Walla (Washington): Developed from French seed stock, this large, flat onion has a juicy, apple-like crunch. Best eaten fresh or grilled.

- Maui (Hawaii): Available spring through summer, Maui onions have a tropical fruit nuance and are excellent raw in seafood dishes.

- Imperial Sweet (California): A more widely available commercial alternative with moderate sweetness and longer shelf life than regional varieties.

Yellow Onion Subtypes

While “yellow onion” typically refers to the standard globe-shaped variety found in supermarkets, subtle variations exist:

- Spanish Onion: Often mistaken for a sweet onion due to its large size and lighter color, Spanish onions are actually a type of yellow onion with a milder profile—but still more pungent than true sweet onions.

- Storage vs. Fresh Harvest: Late-season yellow onions are cured for long-term storage and develop stronger flavor. Early-harvest “green” or “fresh” yellow onions are milder and better for eating raw.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Confusion often arises between sweet onions, yellow onions, white onions, and red onions. While all are edible alliums, their roles differ:

| Onion Type | Flavor | Best Uses | Substitution Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow Onion | Sharp raw, deeply savory when cooked | Base for soups, stews, sauces, roasts | Can replace sweet onion in cooked dishes, but will add more bite |

| Sweet Onion | Mild, sweet, low pungency | Raw salads, grilling, quick sauté, onion rings | Not ideal for long cooking; may become mushy or burnt |

| White Onion | Crisp, sharp, clean heat | Mexican cuisine, salsas, pickling | Closest substitute for yellow in raw applications |

| Red Onion | Peppery with fruity undertones | Salads, pickling, garnishes, sandwiches | Adds color; more acidic than yellow or sweet |

“The difference between a good dish and a great one often lies in onion selection. I reach for yellow onions when building flavor over time, and sweet onions when I want the onion itself to be the star.”

— Chef Elena Martinez, Culinary Instructor, San Francisco Cooking School

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I substitute sweet onions for yellow onions?

Yes, but with caveats. In slow-cooked dishes, sweet onions may break down too quickly and lack the depth of flavor that yellow onions provide. For raw or fast-cooked recipes, sweet onions can enhance palatability. Adjust seasoning accordingly—sweet onions may require less sugar or balancing acid.

How should I store each type?

Store whole yellow onions in a cool, dark, well-ventilated space (e.g., pantry). Keep them away from potatoes, which emit ethylene gas and accelerate spoilage. Sweet onions, due to higher moisture, benefit from refrigeration once cut or if not used within two weeks. Wrap in paper towels to absorb excess moisture and extend life.

Why do sweet onions make better onion rings?

Their large diameter allows for uniform rings, and their natural sugars promote even browning. Combined with low sulfur, they produce a crisp, sweet fry without the acrid aftertaste sometimes associated with yellow onion rings.

Do sweet onions have health benefits?

All onions are rich in antioxidants, particularly quercetin, and support cardiovascular and immune health. While sweet onions contain slightly less sulfur than yellow onions, they still offer anti-inflammatory properties. However, their higher sugar content (though natural) means slightly more carbohydrates per serving.

Are there frozen or dried versions?

Dried minced yellow onion is common in spice blends and instant foods. Sweet onions are rarely dehydrated due to poor texture retention. Frozen sweet onion slices exist but often lose structure and are best used in cooked dishes like soups or casseroles where texture is less critical.

What about cooking times?

Because sweet onions contain more water, they take longer to sweat or caramelize. Expect an additional 10–15 minutes when substituting sweet for yellow in recipes requiring softening. Stir frequently and avoid high heat to prevent burning before moisture evaporates.

Checklist: Choosing the Right Onion

- Need a flavor foundation for soup, stew, or sauce? → Yellow onion

- Serving raw in salad, sandwich, or salsa? → Sweet or red onion

- Grilling or making onion rings? → Sweet onion

- Want long storage without spoilage? → Yellow onion

- Looking for mildness and natural sweetness? → Sweet onion (in season)

Summary & Key Takeaways

The distinction between sweet and yellow onions is not merely semantic—it’s biochemical, seasonal, and functional. Yellow onions, with their high sulfur and low moisture, are engineered by nature and agriculture to build deep, layered flavors through cooking. They are indispensable in foundational techniques like sweating, caramelizing, and stock-making.

Sweet onions, cultivated in specific low-sulfur regions, prioritize palatability and immediate appeal. Their high water and sugar content make them ideal for raw consumption, grilling, and dishes where the onion should complement rather than command attention.

Understanding these differences allows cooks to match the ingredient to the intent. Using a sweet onion in a beef bourguignon may yield a pleasant but underdeveloped sauce; using a raw yellow onion in a tomato salad might overwhelm delicate flavors. Precision in selection elevates execution.

Remember: Seasonality matters. Seek out sweet onions during their peak months for the best quality. Store them properly to maximize freshness. And when in doubt, taste before using—your palate is the ultimate guide.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?