Understanding the distinction between yellow and sweet onions is essential for any cook who values depth of flavor, balance, and precision in the kitchen. Though they may look similar at first glance—both golden-hued and layered beneath papery skins—their chemical composition, taste profiles, and culinary applications differ significantly. Choosing the wrong onion can tilt a dish from savory richness to overwhelming sharpness or, conversely, leave it lacking in backbone. For home cooks aiming to elevate everything from soups and stews to salsas and roasts, knowing when to reach for a yellow onion versus a sweet onion makes all the difference.

Definition & Overview

Onions are fundamental aromatics in global cuisines, forming the base of countless dishes across cultures. Among the most commonly used varieties in North American kitchens are yellow onions and sweet onions. Both belong to the Allium cepa species but have been cultivated for different purposes—one optimized for robust flavor development through cooking, the other bred specifically for mildness and fresh eating.

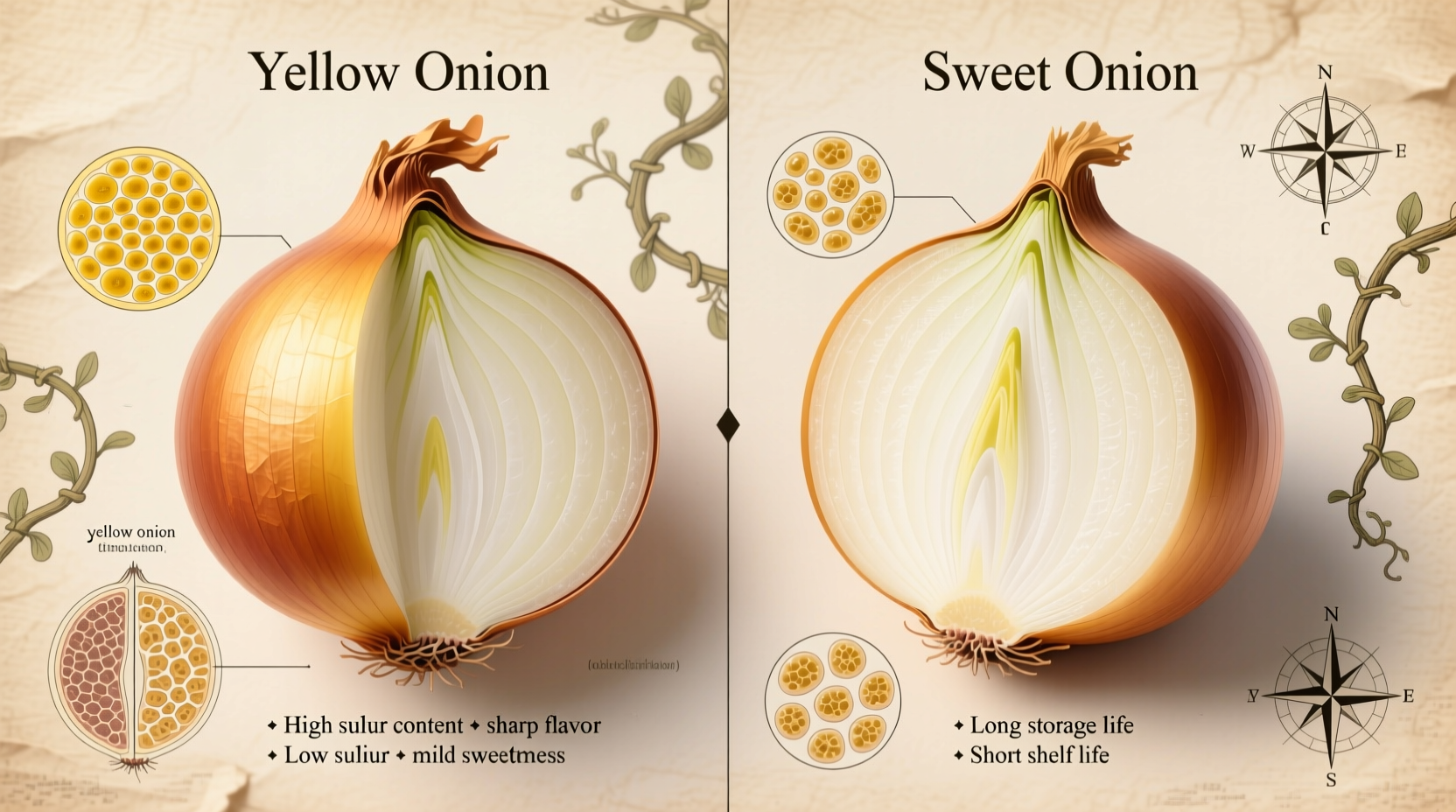

Yellow onions are the workhorse of the onion family. With a tan-to-brown outer skin and pale yellow flesh, they possess a pungent, sulfur-rich profile when raw that mellows into deep umami and sweetness when sautéed, roasted, or caramelized. They are typically smaller and denser than their sweet counterparts and store exceptionally well.

Sweet onions, such as Vidalia, Walla Walla, and Texas 1015, are grown in low-sulfur soils—primarily in specific regions like Georgia, Washington, and Texas—which results in naturally lower pyruvic acid levels. This biochemical difference translates to a noticeably milder, almost fruity taste with minimal bite. Their high water content contributes to their juiciness but also limits shelf life.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Yellow Onion | Sweet Onion |

|---|---|---|

| Flavor (Raw) | Sharp, pungent, moderately spicy with strong sulfur notes | Mild, subtly sweet, almost juicy with little to no burn |

| Flavor (Cooked) | Rich, deeply savory; develops complex sweetness over time | Delicate sweetness; can caramelize quickly but lacks depth if cooked too long |

| Aroma | Pronounced, eye-watering when cut | Subtle, faintly floral or grassy |

| Color & Form | Tan/brown skin, off-white to golden flesh; round and compact | Pale gold to light brown skin, white to pale yellow flesh; often larger and flatter |

| Moisture Content | Lower moisture, denser texture | Higher water content, crisp and juicy |

| Shelf Life | 3–4 months in cool, dry storage | 2–4 weeks; best refrigerated after opening or in warm climates |

| Culinary Function | Aromatic base for sauces, soups, braises, roasts | Fresh applications, grilling, quick sautés, sandwiches |

| Best Season | Available year-round | Spring to early summer (March–July), depending on region |

Practical Usage: How to Use Each Onion Type

The decision between yellow and sweet onions should be driven by both preparation method and desired outcome. Substituting one for the other without adjustment can lead to imbalanced flavors or textural issues.

When to Use Yellow Onions

Yellow onions are ideal when building foundational flavor in cooked dishes. Their high sulfur content breaks down during prolonged heat exposure, transforming harshness into rich, nutty complexity.

- Sautéing and sweating: Start most savory dishes—soups, stews, curries, stir-fries—with finely diced yellow onion. Cooked slowly in fat, they release sugars and form the aromatic base known as *sofrito*, *mirepoix*, or *basse*.

- Caramelizing: Due to their balanced sugar-to-water ratio, yellow onions caramelize beautifully over 30–45 minutes. The result is a jam-like condiment perfect for burgers, pizzas, or cheese boards.

- Braising and roasting: Whole or halved yellow onions add body to stocks and gravies. Roasted alongside meats or vegetables, they contribute earthy sweetness without disintegrating.

- Long-cooked sauces: In tomato sauce, chili, or gumbo, yellow onions integrate fully, enhancing depth without dominating.

When to Use Sweet Onions

Sweet onions shine where minimal cooking—or none at all—is involved. Their delicate nature means they don’t withstand extended heat as well, but their freshness elevates raw preparations.

- Raw applications: Slice thinly into salads, salsas, pico de gallo, or guacamole. Their lack of bite allows other ingredients to stand out while adding crunch and subtle sweetness.

- Grilling and broiling: Because of their high moisture, sweet onions grill well—especially when brushed with oil and seared quickly. They develop charred edges and soft interiors ideal for sandwiches or tacos.

- Quick sautés: Sauté over medium-high heat for 5–8 minutes to retain structure and brightness. Overcooking leads to mushiness and loss of nuanced flavor.

- Onion rings: Sweet onions are preferred for frying due to their tender texture and inherent sweetness, which balances the richness of batter and oil.

- Garnishes: Use raw slivers on top of fish tacos, burgers, or grain bowls for a refreshing contrast.

Pro Tip: When substituting sweet onions for yellow in cooked dishes, reduce liquid slightly and monitor closely—sweet onions release more water and can extend cooking times or dilute flavors. Conversely, using yellow onions raw in place of sweet ones may require soaking in cold water for 10 minutes to temper sharpness.

Variants & Types

While “yellow onion” and “sweet onion” serve as broad categories, several named cultivars exist within each group, each with regional significance and slight variations in taste and texture.

Common Yellow Onion Varieties

- Spanish Onion: Often mistaken for a sweet onion due to its large size and mildness, true Spanish onions are actually a type of yellow onion. They are less pungent than standard yellow onions but still contain enough sulfur to perform well in cooking.

- Italian Torpedo Onion: Elongated and slightly sweeter than typical yellow onions, these are excellent for roasting and grilling. Despite the name, they are not technically “sweet onions” under U.S. agricultural definitions.

Protected Sweet Onion Cultivars

Some sweet onions are legally protected by geographical indication, meaning only those grown in designated regions can bear the name.

- Vidalia (Georgia): Grown in 20 counties in southeastern Georgia, Vidalias are renowned for their honeyed flavor and low acidity. Protected under federal marketing order since 1986.

- Walla Walla (Washington): Developed from French stock in the early 20th century, these large, flat onions have a crisp texture and are best eaten fresh or grilled.

- Texas 1015 (Texas Super Sweet): Named after its October 15 planting date, this variety was developed by USDA scientists to thrive in Texas soil. Exceptionally sweet and juicy, available spring through summer.

- Maui Onion (Hawaii): Grown on the island of Maui, these have a short season and are prized for their delicate flavor. Similar in profile to Vidalia but with a slightly more tropical nuance.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Confusion often arises among yellow onions, sweet onions, white onions, red onions, and shallots. While all are edible alliums, their roles in cooking vary widely.

| Onion Type | Flavor Profile | Best Uses | Distinguishing Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow Onion | Pungent raw, deeply savory when cooked | Base for soups, stews, sauces, roasts | High sulfur, long shelf life |

| Sweet Onion | Mild, juicy, barely spicy | Raw salads, grilling, quick sautés, onion rings | Grown in low-sulfur soil, seasonal |

| White Onion | Crisp, clean, slightly hotter than yellow | Mexican cuisine, salsas, pickling | Thin skin, higher moisture than yellow |

| Red Onion | Peppery with a hint of fruitiness | Salads, sandwiches, pickled red onions | Vibrant color, moderate bite |

| Shallot | Garlicky, refined, subtly sweet | Vinaigrettes, deglazing, fine sauces | Cluster-forming, expensive, gourmet staple |

“The secret to great flavor starts before you even turn on the stove. Choosing the right onion is like selecting the right instrument for an orchestra—it sets the tone.”

— Chef Elena Martinez, Culinary Instructor at Pacific Coast Cooking Academy

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I substitute sweet onions for yellow onions in recipes?

Yes, but with caveats. In slow-cooked dishes, sweet onions may break down faster and introduce excess moisture. Reduce added liquids and consider combining half sweet, half yellow onion to preserve structure and depth. For raw uses, never substitute standard yellow onions unless soaked in ice water to reduce pungency.

How do I store each type properly?

Yellow onions keep best in a cool, dark, well-ventilated space—like a pantry or cellar—at temperatures between 45°F and 55°F (7°C–13°C). Avoid plastic bags; use mesh produce bags or baskets to allow airflow. Do not refrigerate whole yellow onions—they absorb moisture and spoil faster.

Sweet onions, due to higher water content, are more perishable. Store uncut bulbs in the refrigerator crisper drawer in a paper bag to wick away moisture. Once cut, wrap tightly in plastic or store in an airtight container for up to 5 days.

Why do some sweet onions cost more?

Premium pricing reflects limited growing seasons, geographical restrictions, and labor-intensive harvesting. Vidalias, for example, are only harvested once per year and must meet strict state-regulated standards. Their short availability and high demand drive prices upward compared to commodity yellow onions.

Do sweet onions have fewer tears?

Yes. The compounds that cause eye irritation—syn-propanethial-S-oxide—are derived from sulfur. Since sweet onions grow in low-sulfur soil, they produce less of this volatile gas. Cutting a Vidalia is noticeably gentler on the eyes than chopping a yellow onion.

Are sweet onions healthier?

All onions offer health benefits, including antioxidants (quercetin), anti-inflammatory properties, and prebiotic fiber. Yellow onions contain slightly more sulfur compounds, linked to detoxification support, while sweet onions provide more vitamin C per serving due to fresher consumption patterns. Nutritionally, the differences are marginal—choose based on culinary need, not health claims.

What about frozen or dried alternatives?

Frozen diced onions are typically made from yellow varieties and work acceptably in soups or casseroles but lack texture for fresh use. Dried minced onion rehydrates poorly and should not replace fresh in raw dishes. Neither replicates the unique qualities of sweet onions, which rely heavily on juiciness and subtlety.

Checklist: Choosing the Right Onion at the Market

- For cooking: Pick firm yellow onions with dry, papery skin—no sprouting or soft spots.

- For raw eating: Select heavy-for-size sweet onions with tight necks and no bruises.

- Smell test: A strong odor indicates age or fermentation—avoid.

- Seasonality matters: Buy Vidalias March–June, Walla Wallas May–August.

- Label check: Look for “Vidalia,” “Walla Walla,” or “Texas 1015” branding to ensure authenticity.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Yellow and sweet onions are not interchangeable without consequence. Recognizing their fundamental differences ensures better control over flavor, texture, and overall dish balance.

- Yellow onions are the foundation of savory cooking—pungent when raw, deeply flavorful when cooked. Use them whenever building layers of taste in soups, stews, sauces, and roasted dishes.

- Sweet onions excel in fresh or lightly cooked preparations. Their low sulfur content delivers natural sweetness and minimal bite, making them ideal for salads, salsas, grilling, and garnishes.

- Storage differs: yellow onions last months in cool, dry conditions; sweet onions require refrigeration and consume within weeks.

- Named varieties like Vidalia, Walla Walla, and Texas 1015 are legally protected and represent peak-season specialty items—not just marketing terms.

- Substitution is possible but requires adjustments—especially managing moisture and cooking time.

Mastering the role of each onion empowers cooks to make intentional choices, turning routine meals into thoughtfully crafted experiences. Whether you're deglazing a pan or topping a taco, let the onion guide you—not just as an ingredient, but as a voice in the language of flavor.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?