In an age where desk jobs dominate and screen time is at an all-time high, poor posture has become a widespread concern. Rounded shoulders, forward head position, and slumped sitting are now common postural patterns—so much so that the market for posture corrector braces has exploded. From sleek fabric straps to rigid back supports, these devices promise to “fix” your posture in weeks. But do they actually work? Or are they creating a physical dependency that weakens the very muscles they claim to help?

The truth lies somewhere in between. Posture correctors can offer short-term relief and awareness, but their long-term value depends on how—and why—you use them. To understand whether these braces are a solution or a crutch, it’s essential to examine the science behind posture, muscle function, and corrective strategies.

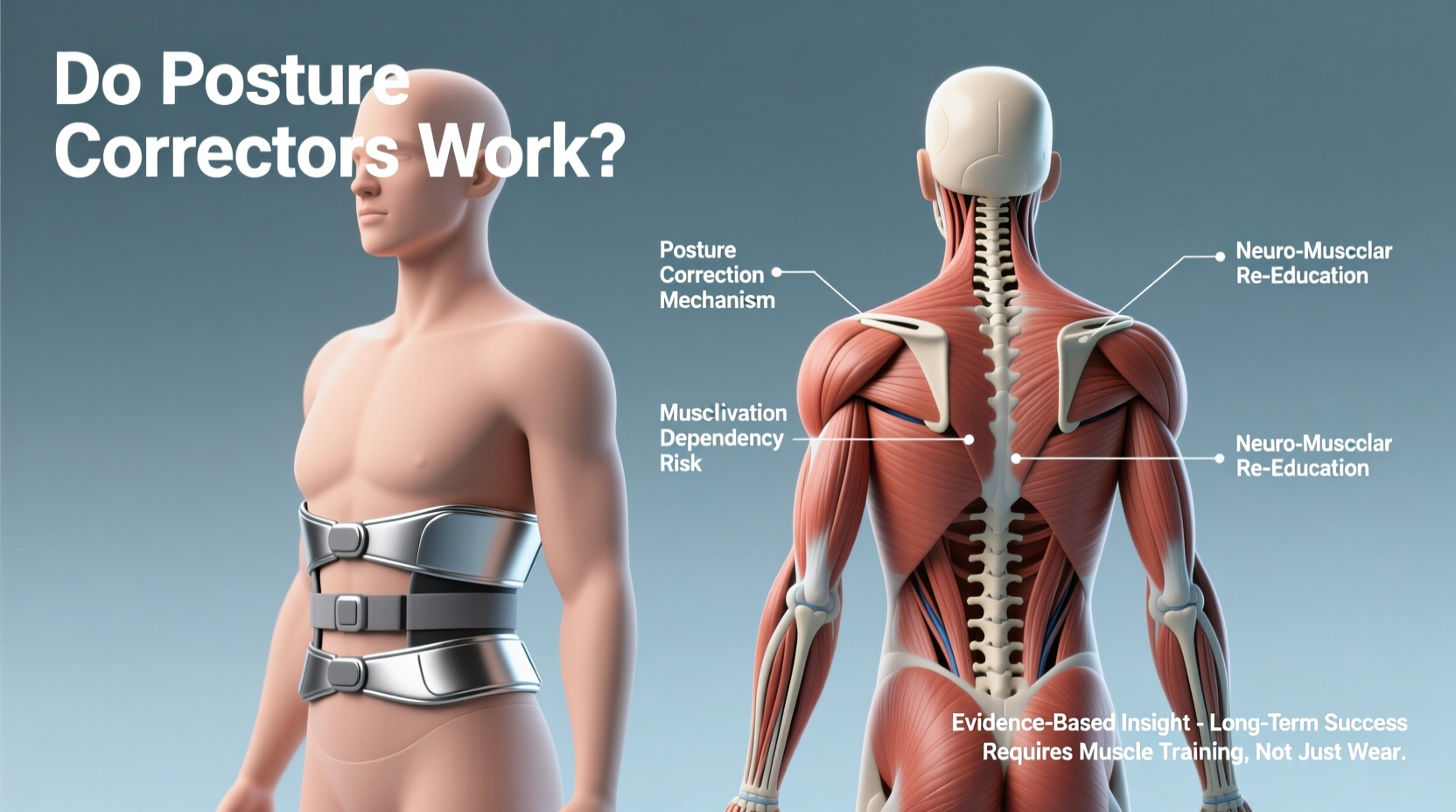

How Posture Correctors Claim to Work

Posture corrector braces operate on a simple mechanical principle: they physically pull the shoulders back and align the spine into what’s considered a “neutral” position. Most designs feature adjustable straps that wrap around the upper arms and chest, gently guiding the shoulders into retraction. Others include rigid supports along the spine to limit forward bending.

Manufacturers often claim benefits such as:

- Reduced neck and back pain

- Improved breathing and energy levels

- Enhanced confidence due to upright appearance

- Faster correction of years of poor posture

For many users, the immediate effect is undeniable. Slouching becomes uncomfortable, while standing tall feels enforced. However, this raises a critical question: is the improvement coming from muscular retraining—or simply external support?

The Science Behind Muscle Memory and Dependency

Muscles adapt based on demand. When a posture corrector does the job of holding your shoulders back, the rhomboids, lower trapezius, and deep cervical flexors—the key postural stabilizers—become less active. Over time, this disuse can lead to neuromuscular inhibition, where the brain \"forgets\" how to properly engage these muscles without external cues.

This phenomenon mirrors what happens with orthotic shoe inserts or wrist braces: helpful in acute injury or rehabilitation, but potentially problematic if used indefinitely without strengthening the underlying structures.

“Braces can be useful tools during early stages of postural re-education, but they should never replace active muscle engagement.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Physical Therapist and Spine Health Specialist

A 2020 study published in the *Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies* found that participants who wore posture braces for more than four hours daily over six weeks showed no significant improvement in postural control once the brace was removed. In contrast, those who combined limited brace use (30–60 minutes/day) with targeted exercises demonstrated measurable gains in muscular endurance and postural awareness.

When Posture Braces Help—And When They Don’t

Not all posture correctors are inherently flawed. Their effectiveness depends heavily on context, duration of use, and integration with other interventions.

Situations Where Braces Can Be Beneficial

- Short-term postural cueing: Wearing a brace briefly during prolonged sitting can serve as a reminder to sit up straight.

- Rehabilitation support: After shoulder or spinal injury, a brace may prevent harmful movements during healing.

- Behavioral feedback: For individuals unaware of their slouching, the brace acts like a biofeedback device.

Scenarios Where Braces Cause Harm

- Daily long-term wear: Extended use leads to muscle atrophy and reliance.

- Pain masking: Users may ignore discomfort signals, leading to overuse injuries.

- Improper fit: Tight or misaligned braces can compress nerves or restrict breathing.

Step-by-Step Guide to Using a Posture Corrector Safely

If you choose to try a posture corrector, follow this structured approach to avoid dependency and maximize benefit:

- Assess your current posture. Take side-view photos of yourself standing naturally. Note head position, shoulder alignment, and spinal curves.

- Select a comfortable, adjustable brace. Avoid rigid models unless prescribed by a healthcare provider.

- Start with short durations. Wear the brace for 15–20 minutes per day during sedentary tasks.

- Pair it with exercises. Perform rows, scapular retractions, chin tucks, and core activation drills while wearing or immediately after removing the brace.

- Gradually reduce usage. Aim to rely on the brace less each week. By week 6, use it only occasionally for feedback.

- Retest your posture. Repeat initial photos and compare changes. Focus on ability to maintain alignment without support.

Alternatives That Build Real Postural Strength

The most sustainable way to improve posture isn’t through external devices—it’s through consistent neuromuscular training. Unlike braces, these methods build intrinsic stability and resilience.

Key Exercises for Postural Integrity

- Chin Tucks: Counteracts forward head posture. Perform 2 sets of 10 daily.

- Prone Y-T-W Raises: Activates lower traps and rear deltoids. Lie face down, arms extended in Y, T, and W shapes.

- Wall Angels: Stand with back against wall, slide arms up and down slowly while maintaining contact.

- Dead Bugs: Builds core stability, preventing compensatory arching in the lower back.

- Thoracic Spine Mobility Drills: Use foam rollers to restore mid-back extension lost from sitting.

Consistency matters more than intensity. Just 10–15 minutes of daily postural exercise yields better long-term results than hours spent strapped into a brace.

Environmental Modifications

Posture is shaped by behavior and environment. Optimizing your workspace reduces strain before it begins:

- Position computer screens at eye level

- Use an ergonomic chair with lumbar support

- Take micro-breaks every 30 minutes to stand and stretch

- Alternate between sitting and standing throughout the day

Real Example: Sarah’s Journey from Brace to Independence

Sarah, a 34-year-old graphic designer, began experiencing chronic neck pain after transitioning to remote work. She purchased a popular posture corrector online and wore it for 4–6 hours daily. Initially, her pain decreased and she felt taller. But after two months, she noticed increased fatigue in her upper back and couldn’t sit comfortably without the brace.

She consulted a physical therapist who advised her to stop full-time use immediately. Instead, she started a program including chin tucks, seated scapular squeezes, and thoracic extensions. She wore the brace only for 20 minutes during her longest work session, using it as a reminder—not a support.

Within eight weeks, Sarah could maintain good posture unaided. Her pain diminished, and she reported improved breathing and focus. The brace hadn’t fixed her posture—but the awareness it provided, combined with targeted exercise, did.

Comparison Table: Braces vs. Active Postural Training

| Factor | Posture Corrector Braces | Active Postural Training |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate Effect | High – forces alignment | Low – requires practice |

| Long-Term Results | Poor without exercise | Strong and sustainable |

| Muscle Engagement | Reduces natural activation | Enhances strength and control |

| Risk of Dependency | High with prolonged use | None |

| Cost Over Time | $30–$100 one-time | Minimal (bodyweight exercises) |

| Best For | Short-term feedback | Permanent postural change |

FAQ: Common Questions About Posture Correctors

Can posture correctors fix kyphosis or scoliosis?

No. While mild postural kyphosis (rounding of the upper back) may improve with behavioral changes, structural conditions like Scheuermann’s kyphosis or scoliosis require medical evaluation and targeted treatment. Braces prescribed by orthopedic specialists for these conditions are different from over-the-counter correctors and are used under strict supervision.

How long should I wear a posture brace each day?

Limited use is key. Start with 15–30 minutes once or twice daily. Never exceed 2 hours total per day, and avoid wearing it during physical activity or sleep. The goal is awareness, not constant correction.

Will my posture get worse if I stop using the brace?

It might—if you haven’t built the muscular strength to maintain alignment independently. This is known as dependency. To prevent regression, transition out of brace use gradually while building postural endurance through exercise.

Checklist: Healthy Posture Improvement Plan

Follow this checklist to improve posture safely and sustainably:

- ☑ Assess your posture with front/side photos

- ☑ Limit brace use to 15–30 minutes/day (if used at all)

- ☑ Perform chin tucks and scapular retractions daily

- ☑ Incorporate 3 postural exercises 4x per week

- ☑ Adjust workstation to support neutral spine

- ☑ Take standing breaks every 30 minutes

- ☑ Retest posture progress monthly

- ☑ Consult a physical therapist if pain persists

Conclusion: Tools Are Not Solutions

Posture corrector braces are not inherently bad—but they are often misused. Like crutches after an ankle sprain, they can provide temporary support during recovery. But if you never strengthen the injured limb, you’ll never walk unaided. The same applies to posture.

True postural improvement comes from consistent movement, muscle activation, and environmental awareness. Devices may offer a starting point, but lasting change requires active participation. Instead of asking whether a brace works, ask whether it empowers you to stand stronger on your own.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?