In an age where desk jobs dominate and screen time continues to rise, slouching has become almost second nature. Many people turn to posture correctors—those snug straps worn across the shoulders and back—in hopes of reclaiming upright alignment. But do these devices truly fix poor posture, or do they merely mask the problem while creating a new one: physical dependency? The answer isn’t as simple as marketing claims suggest. While some users report immediate relief and improved awareness, others find themselves unable to sit straight without the aid of their brace. This article dives deep into the mechanics, medical insights, and long-term implications of using posture correctors, separating fact from fitness fad.

The Science Behind Posture Correctors

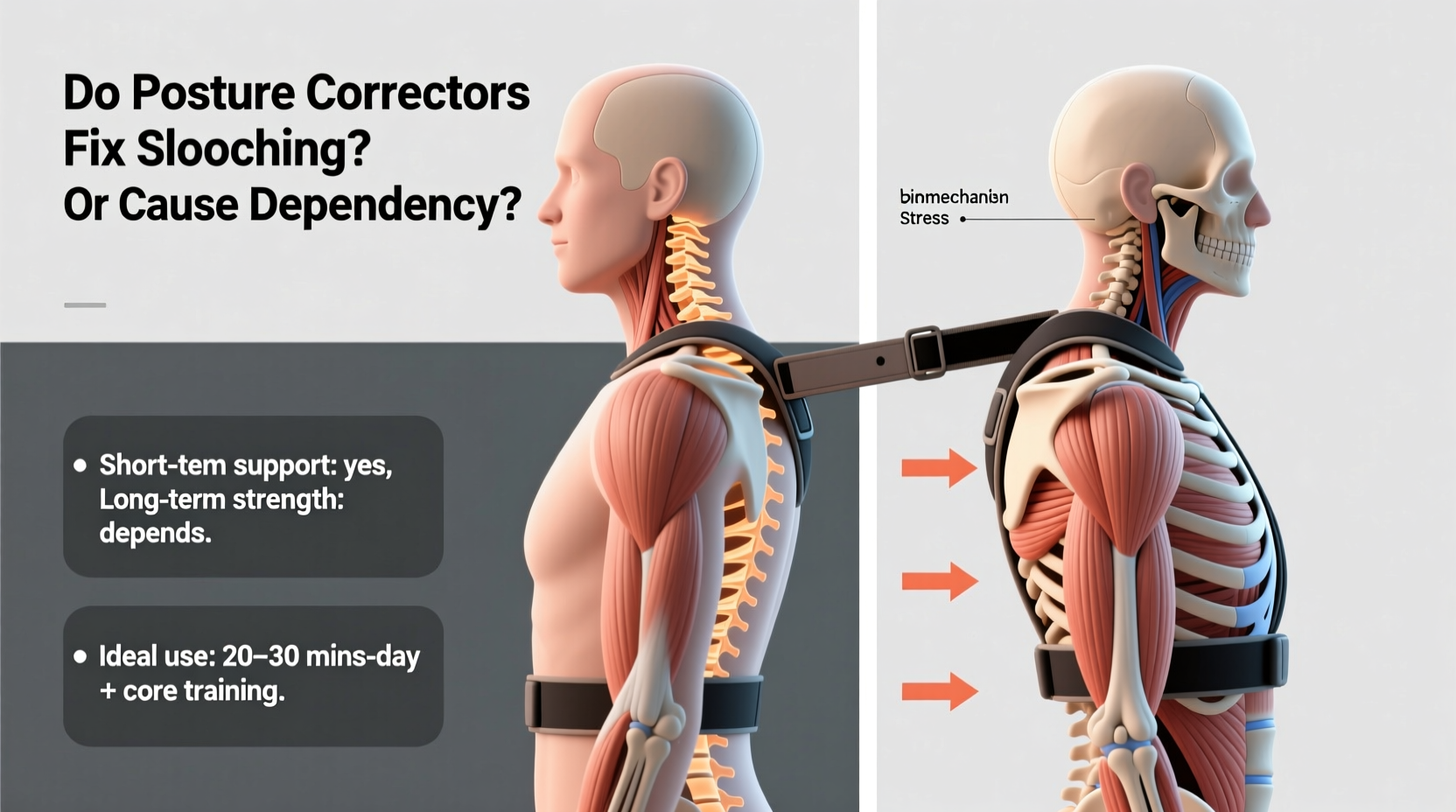

Posture correctors work on a basic biomechanical principle: external support forces the body into a desired position. Most models pull the shoulders back and slightly elevate the chest, mimicking what is commonly referred to as \"neutral spine alignment.\" By doing so, they reduce the forward head posture and rounded shoulders associated with prolonged sitting or smartphone use.

From a short-term perspective, this can be beneficial. A 2020 study published in the *Journal of Physical Therapy Science* found that wearing a posture corrector for 30 minutes led to measurable improvements in thoracic kyphosis (upper back curvature) and shoulder positioning. However, the same study noted no lasting changes after the device was removed, suggesting that the effects were purely positional, not functional.

The human body adapts to habitual movement patterns. When muscles are underused—such as the lower trapezius and serratus anterior in chronic slouchers—they weaken over time. Meanwhile, opposing muscles like the pectoralis minor tighten. A posture corrector may temporarily counteract this imbalance, but it doesn’t address the root neuromuscular causes. In essence, it’s like using crutches for a weak ankle without ever doing rehabilitation exercises.

“Bracing can provide sensory feedback, which is helpful initially. But true postural correction comes from muscle re-education, not passive support.” — Dr. Lena Torres, DPT, Board-Certified Orthopedic Specialist

Benefits vs. Risks: A Balanced View

Like any assistive device, posture correctors come with both advantages and drawbacks. Understanding them helps users make informed decisions about whether—and how—to incorporate them into daily life.

Short-Term Benefits

- Immediate postural feedback: Users often feel more aware of their alignment when wearing a brace.

- Pain reduction: Some individuals with upper back or neck discomfort report temporary relief due to reduced strain on spinal structures.

- Habit interruption: Wearing a corrector can break the cycle of unconscious slouching during work hours.

Potential Risks and Downsides

- Muscle atrophy: Relying on external support may lead to further weakening of postural muscles over time.

- Dependency: Users may feel unable to maintain good posture without the device, especially if used excessively.

- Skin irritation and restricted breathing: Poorly fitted or overly tight braces can cause chafing or limit diaphragmatic expansion.

- False sense of progress: Looking “straight” doesn’t mean the underlying dysfunction has been corrected.

When Posture Correctors Help—And When They Don’t

Not all users are the same, and context matters. For some, a posture corrector can be a useful transitional tool. For others, it may delay meaningful recovery.

Situations Where Correctors May Be Beneficial

- Rehabilitation phase: After an injury or surgery affecting the upper back, a brace might support healing under professional guidance.

- Neuromuscular retraining: When combined with physical therapy, the device can serve as a biofeedback tool to reinforce proper alignment.

- Occupational necessity: For individuals required to sit for extended periods (e.g., call center workers), brief use may interrupt harmful patterns.

Scenarios Where They’re Likely Harmful

- Long-term daily use: Wearing a brace for hours every day trains the body to rely on external structure rather than internal strength.

- Without exercise integration: If no effort is made to strengthen core and scapular stabilizers, the root issue remains unaddressed.

- Ignoring pain signals: Pushing through discomfort to “toughen up” in a brace can lead to nerve compression or soft tissue damage.

Mini Case Study: Sarah’s Experience

Sarah, a 32-year-old graphic designer, began experiencing neck stiffness and fatigue after transitioning to remote work. She purchased an online posture corrector and wore it for four hours daily. Initially, she felt taller and more confident. Within three weeks, however, she noticed increased reliance—her shoulders would slump the moment she removed the brace. After consulting a physical therapist, she learned her mid-back muscles had weakened from disuse. Her treatment plan included discontinuing full-time brace use and starting targeted exercises. Over eight weeks, she regained natural postural control without assistance.

Building Sustainable Posture: A Step-by-Step Guide

Lasting postural improvement requires active engagement, not passive support. Here’s a practical, science-backed timeline to develop stronger, self-sustaining posture.

Weeks 1–2: Awareness & Environment Setup

- Set reminders every 30 minutes to check your posture.

- Evaluate your workspace: Ensure your monitor is at eye level, elbows bent at 90°, and feet flat on the floor.

- Practice the “stack” technique: Align ears over shoulders, shoulders over hips, hips over ankles.

Weeks 3–6: Introduce Foundational Exercises

- Chin tucks: 3 sets of 10, twice daily to combat forward head posture.

- Scapular retractions: Squeeze shoulder blades together while seated; hold for 5 seconds, repeat 15 times.

- Wall angels: Stand with back against a wall, arms in goalpost position, and slide arms up and down slowly. 2 sets of 10.

Weeks 7–12: Strengthen & Integrate

- Add resistance training: Rows, face pulls, and deadlifts build postural muscle endurance.

- Incorporate yoga or Pilates: These improve body awareness and core stability.

- Gradually reduce any brace use, reserving it only for short feedback sessions.

Ongoing Maintenance

Posture isn’t fixed—it’s maintained. Continue integrating micro-movements throughout the day: standing breaks, dynamic stretches, and mindful sitting. Think of posture like dental hygiene: daily effort prevents long-term decay.

Expert-Recommended Checklist for Postural Health

- ✅ Assess workstation ergonomics monthly

- ✅ Perform chin tucks and scapular squeezes daily

- ✅ Take a standing or walking break every 30–45 minutes

- ✅ Engage in strength training 2–3 times per week

- ✅ Limit posture corrector use to ≤30 minutes/day

- ✅ Schedule a posture screening with a physical therapist annually

- ✅ Practice diaphragmatic breathing to support spinal alignment

Comparison Table: Posture Correctors vs. Active Postural Training

| Factor | Posture Correctors | Active Postural Training |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate Effect | High – visible change in alignment | Low to moderate – gradual awareness |

| Long-Term Improvement | Limited – risk of dependency | High – sustainable muscle adaptation |

| Cost | $20–$80 one-time purchase | Minimal (bodyweight exercises) or gym membership |

| Risk of Injury | Moderate – skin irritation, muscle inhibition | Low – when done correctly |

| Time Commitment | Passive – wear and forget | Active – 10–20 mins/day recommended |

| Professional Endorsement | Conditional – short-term use only | Strongly recommended by PTs and chiropractors |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can posture correctors permanently fix slouching?

No. Posture correctors cannot produce permanent change because they don’t strengthen the muscles responsible for maintaining alignment. Lasting correction requires neuromuscular re-education through consistent exercise and habit modification. Braces may help early in the process, but they are not a standalone solution.

How long should I wear a posture corrector each day?

Experts recommend limiting use to 20–30 minutes once or twice per day, especially during initial use. Prolonged wear can inhibit muscle activation and lead to dependency. Think of it as a reminder tool, similar to a vibrating smartwatch alerting you to stand up—not something to wear all day.

Are there alternatives to posture correctors?

Yes. Effective alternatives include ergonomic workstation adjustments, regular stretching, strength training (especially for the upper back and core), and mindfulness practices like yoga or Alexander Technique. Additionally, wearable posture trainers that vibrate when you slouch—without providing physical support—can offer feedback without encouraging dependency.

Conclusion: Toward True Postural Independence

Posture correctors are not inherently bad—but they are often misused. When treated as a quick fix, they can create a false sense of progress while allowing the underlying muscular imbalances to worsen. Real postural health isn’t about being pulled into place by straps; it’s about building the strength, awareness, and habits that allow the body to hold itself naturally and efficiently.

The goal shouldn’t be to depend on a device, but to outgrow the need for one. By combining environmental adjustments, targeted exercise, and mindful movement, anyone can transition from forced alignment to functional posture. Start small: set a timer, do a few chin tucks, adjust your chair height. These tiny actions compound into lasting change.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?