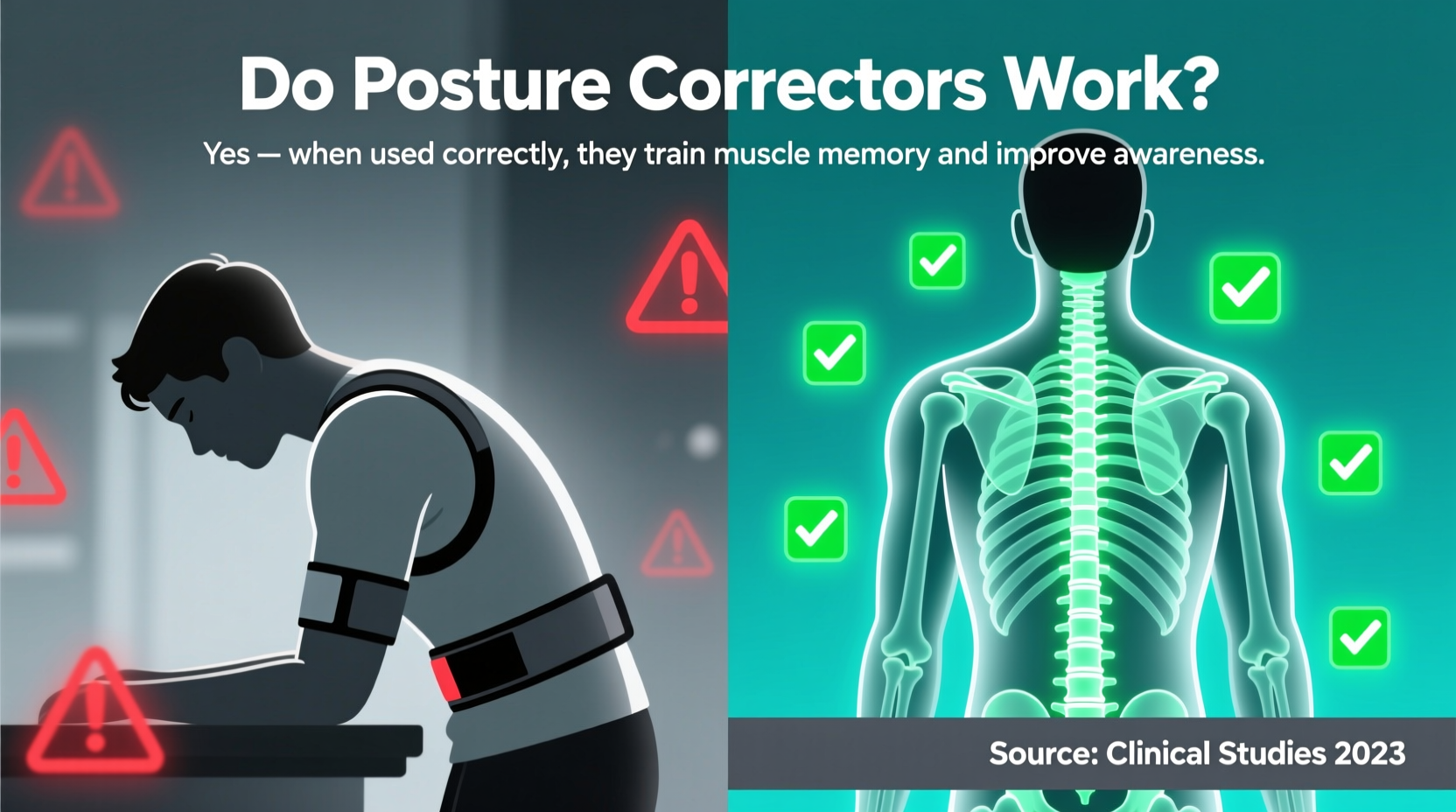

Spend more than ten minutes scrolling through social media or shopping online, and you’ll likely come across a sleek shoulder brace promising to “fix your posture in minutes.” These devices—commonly called posture correctors—are marketed as quick fixes for slouching, back pain, and the dreaded “tech neck” caused by hours spent hunched over phones and laptops. But behind the bold claims lies a critical question: do these gadgets actually deliver lasting benefits, or are they just another uncomfortable trend capitalizing on modern discomfort?

The answer isn’t straightforward. While some users report immediate relief and improved awareness of their posture, others find the braces painful, restrictive, or ineffective over time. To cut through the marketing noise, it’s essential to examine what posture correctors are designed to do, how they interact with human biomechanics, and whether long-term reliance on them supports—or undermines—true postural health.

How Posture Correctors Are Supposed to Work

Posture correctors typically consist of adjustable straps that wrap around the shoulders and upper back, pulling them into a retracted, upright position. The idea is simple: by physically restricting forward shoulder slump, the device forces the spine into alignment, training the body to maintain that posture naturally over time.

Manufacturers often claim these devices “retrain” muscles and improve neuromuscular control—the brain’s ability to communicate with muscles to maintain proper positioning. In theory, consistent use could help reverse years of poor sitting habits, especially among office workers, students, and frequent smartphone users.

Some models include vibration alerts or wearable sensors that signal when the user begins to slouch, adding a behavioral feedback loop. Others are passive, relying solely on physical resistance to encourage upright positioning.

The Science Behind the Claims: What Research Says

Despite widespread popularity, scientific evidence supporting the long-term efficacy of posture correctors remains limited. A 2021 review published in the Journal of Physical Therapy Science analyzed multiple studies on wearable posture support devices and found that while short-term use led to measurable improvements in spinal alignment, these changes were not sustained after discontinuation.

In other words, posture correctors can temporarily alter posture—but they don’t necessarily strengthen the underlying musculature responsible for maintaining it. One study observed that participants who relied solely on braces without accompanying exercise showed no improvement in postural endurance after four weeks.

“Braces may offer a sensory cue, but they don’t replace the need for active muscle engagement. True postural correction comes from strengthening, not strapping.” — Dr. Lena Patel, DPT, Board-Certified Orthopedic Specialist

This aligns with basic principles of motor learning: the body adapts through repetition and resistance. Wearing a brace is passive; real change requires active participation. Think of it like wearing a back belt while lifting weights—it may provide momentary support, but it won’t build core strength.

Common Benefits Reported by Users

Despite the lack of robust clinical backing, many people swear by posture correctors. Common self-reported benefits include:

- Immediate postural awareness: The physical sensation of being pulled upright serves as a constant reminder to sit or stand properly.

- Pain reduction: Some users with mild upper back or neck tension notice short-term relief due to reduced strain on the trapezius and cervical spine.

- Behavioral reinforcement: Devices with vibration alerts can interrupt habitual slouching, helping users develop mindfulness about their posture.

- Placebo effect: The belief that something is improving your condition can itself lead to perceived improvement, even if physiological changes are minimal.

For individuals recovering from minor injuries or adjusting to new ergonomic setups, a posture corrector might serve as a transitional aid—similar to using crutches after a sprain. However, the key word is *transitional*. Long-term dependency can lead to muscle atrophy, where the very muscles needed for good posture become weaker from disuse.

Risks and Drawbacks of Overuse

While generally safe for short-term use, posture correctors carry several potential downsides:

| Risk | Description |

|---|---|

| Muscle Weakness | When external support takes over, postural muscles like the rhomboids and lower trapezius may weaken from underuse. |

| Skin Irritation | Prolonged wear, especially in hot or humid conditions, can cause chafing, rashes, or pressure sores. |

| Overcorrection | Excessive tightening can force the shoulders too far back, leading to joint strain or breathing restriction. |

| Psychological Dependence | Users may feel unable to maintain good posture without the device, undermining confidence in natural alignment. |

Additionally, many off-the-shelf models are one-size-fits-all, failing to account for individual anatomical differences. This can result in improper fit and uneven pressure distribution, potentially exacerbating discomfort rather than alleviating it.

A Realistic Case: Sarah’s Experience

Sarah, a 34-year-old graphic designer, began using a popular posture corrector after months of nagging upper back pain. Initially, she felt taller and more alert. “It was like someone finally opened my chest,” she said. She wore it daily during work hours for three weeks.

But gradually, the discomfort set in. The straps dug into her shoulders, and she noticed her mid-back felt weaker when she wasn’t wearing the brace. After consulting a physical therapist, she learned she had been over-relying on the device instead of addressing the root cause: weak scapular stabilizers and tight pectoral muscles from prolonged sitting.

With a tailored exercise plan focusing on scapular retractions, chin tucks, and thoracic mobility drills, Sarah improved her posture within two months—without needing the brace. “The corrector gave me awareness,” she reflected, “but the real fix came from moving my body differently.”

Better Alternatives: Building Posture From the Inside Out

If posture correctors aren’t a sustainable solution, what is? The most effective approach combines environmental adjustments, movement habits, and targeted strengthening. Unlike braces, these strategies create lasting change by empowering the body to support itself.

Step-by-Step Guide to Natural Posture Improvement

- Assess Your Workspace Ergonomics

Ensure your monitor is at eye level, elbows bent at 90 degrees, and feet flat on the floor. Even small adjustments can reduce forward head posture. - Take Movement Breaks Every 30 Minutes

Stand up, stretch, or walk briefly to reset muscle tension. Set a timer or use a smartwatch to remind you. - Strengthen Key Postural Muscles

Focus on exercises like rows, face pulls, and prone Y-T-W raises to activate the upper back and rear shoulders. - Stretch Tight Chest and Neck Muscles

Doorway stretches for the pectorals and gentle neck side bends can counteract slouching tendencies. - Practice Mindful Alignment Daily

Stand against a wall periodically to check ear-shoulder-hip-ankle alignment. Use mirrors or phone cameras to self-assess.

Checklist: Is a Posture Corrector Right for You?

Before purchasing or relying on a brace, ask yourself the following:

- ✅ Am I using this as a temporary awareness tool, not a permanent fix?

- ✅ Have I consulted a healthcare provider if I have chronic pain or spinal conditions?

- ✅ Am I combining brace use with exercises to strengthen my back and core?

- ✅ Does the device fit comfortably without pinching or restricting breath?

- ❌ Am I expecting it to work without changing my sitting habits or activity levels?

If the last question applies, reconsider. No device can compensate for sedentary behavior or poor ergonomics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can posture correctors fix kyphosis or scoliosis?

No. While mild postural kyphosis (rounded upper back) may improve with behavioral changes, structural conditions like Scheuermann’s kyphosis or scoliosis require medical evaluation and specialized treatment such as physical therapy, bracing prescribed by an orthopedist, or in severe cases, surgery. Over-the-counter posture correctors are not designed or tested for these conditions and may delay proper care.

How long should I wear a posture corrector each day?

If used at all, limit wear to 15–30 minutes initially, gradually increasing to no more than 2 hours per day. Prolonged use increases the risk of muscle dependence and skin irritation. Never wear one while sleeping or during intense physical activity.

Are there any groups who should avoid posture correctors entirely?

Yes. Individuals with respiratory conditions (like asthma or COPD), rib injuries, osteoporosis, or recent shoulder surgery should avoid these devices unless cleared by a physician. The compression can restrict breathing or interfere with healing tissues.

Conclusion: Awareness Over Dependency

Posture correctors are neither miracle cures nor complete scams. For some, they serve as useful biofeedback tools—temporary aids that heighten awareness of poor habits. But they are not substitutes for movement, strength, and ergonomic awareness. Relying on them long-term can do more harm than good by weakening the very systems meant to support upright posture.

True postural health isn’t achieved by strapping yourself into alignment. It’s built through consistent, mindful choices: setting up your workspace correctly, taking breaks to move, and strengthening the muscles that hold you tall. These habits take effort, but they offer something a brace never can—lasting resilience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?