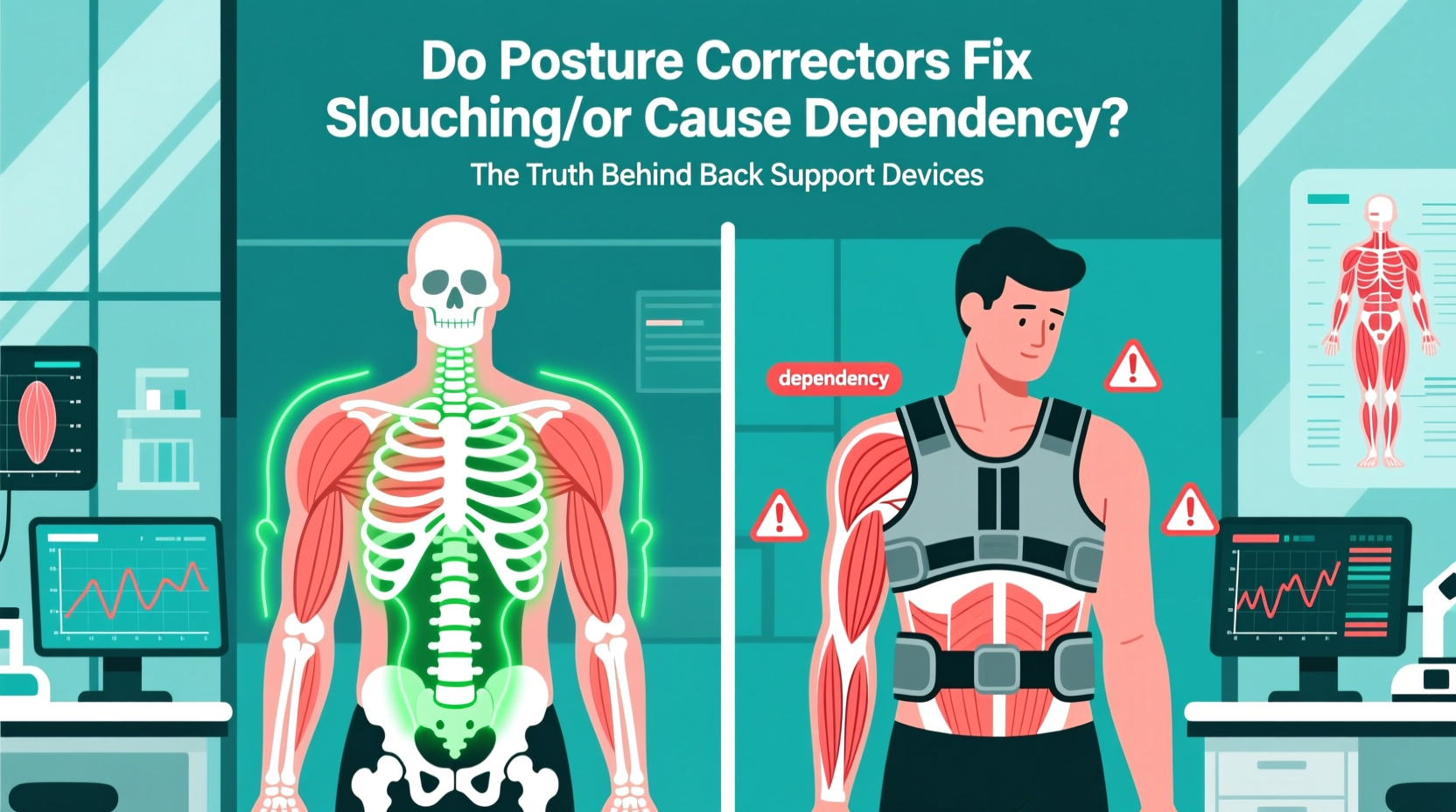

In an era dominated by desk jobs, smartphones, and prolonged sitting, slouching has become a near-universal habit. As awareness grows about the consequences—chronic back pain, reduced lung capacity, and even diminished confidence—many have turned to posture correctors as a quick fix. These wearable devices promise to pull your shoulders back, align your spine, and retrain your body into standing tall. But do they actually correct poor posture, or are they creating a new problem: muscle dependency?

The truth lies somewhere in between. While posture correctors can offer short-term relief and serve as a sensory cue for better alignment, their long-term effectiveness hinges on how they're used. Misused, they may weaken postural muscles over time. Used wisely, they can be part of a broader strategy that includes strength training, mobility work, and behavioral changes.

How Posture Correctors Work

Posture correctors come in various forms—brace-like shirts, shoulder straps, back supports—but most function similarly: they apply gentle but firm pressure to pull the shoulders back and restrict forward rounding of the upper back (kyphosis). This mechanical correction forces the wearer into what appears to be a neutral spinal position.

The immediate effect is often noticeable. Users report feeling taller, more alert, and less fatigued after wearing one for a few hours. Some devices also include vibration alerts when slouching is detected, reinforcing real-time feedback.

However, this correction is external. The device does the work that should ideally be done by the body’s own musculature—specifically the deep neck flexors, lower trapezius, rhomboids, and serratus anterior. When these muscles are weak or inhibited due to prolonged sitting, the body defaults to using stronger, compensatory muscles like the pectorals and upper traps, leading to the classic “hunched” look.

The Risk of Muscle Dependency

Muscle dependency occurs when supportive devices consistently perform the job of stabilizing joints or maintaining alignment, causing the body to \"forget\" how to do it on its own. Think of it like wearing a knee brace every day without strengthening the quadriceps—the joint becomes reliant on external support.

When worn excessively, posture correctors can lead to neuromuscular disengagement. Instead of activating weakened postural muscles, the brain learns to offload that responsibility to the brace. Over weeks or months, this can result in further weakening of critical stabilizers, ironically making slouching worse once the device is removed.

A 2020 study published in the Journal of Physical Therapy Science found that while participants showed improved posture during use, there was no significant carryover after discontinuation unless combined with targeted exercises. In some cases, muscle activation patterns reverted to pre-treatment levels within days.

“Bracing without active re-education is like putting a cast on a limp wrist and expecting strength to return when it’s removed.” — Dr. Lena Torres, DPT, Spine Rehabilitation Specialist

When Posture Correctors Can Help

Despite the risks, posture correctors aren’t inherently harmful. In fact, when used correctly, they can play a valuable role in posture rehabilitation. Here’s where they shine:

- Sensory Feedback: For individuals who’ve lost body awareness (proprioception) of their posture, a corrector acts like a constant reminder, helping them recognize what “good posture” feels like.

- Habit Interruption: Just as a vibrating smartwatch reminds you to stand up, a posture corrector interrupts the automatic slouch, prompting conscious correction.

- Short-Term Relief: People with acute upper back pain or those recovering from surgery may benefit from temporary support while healing.

- Behavioral Training Aid: When paired with mindfulness and corrective exercises, the device becomes a teaching tool rather than a crutch.

The key is intentional, limited use. Experts recommend wearing a posture corrector for no more than 2–4 hours per day, and only as part of a comprehensive plan that includes movement retraining.

Effective Alternatives to Bracing

Sustainable posture improvement doesn’t come from strapping yourself into a harness—it comes from restoring balance to your musculoskeletal system. The human body evolved to move, not to be held in place. Long-term correction requires addressing the root causes of slouching: muscular imbalances, poor ergonomics, and sedentary behavior.

Step-by-Step Guide to Building Natural Postural Strength

- Assess Your Daily Habits

Track how many hours you spend sitting, looking down at screens, or carrying heavy bags on one shoulder. Awareness is the first step toward change. - Optimize Your Workspace

Ensure your monitor is at eye level, elbows bent at 90°, and feet flat on the floor. Consider a sit-stand desk to encourage movement. - Perform Daily Mobility Drills

Spend 5–10 minutes loosening tight areas: pec stretches, chin tucks, thoracic extensions over a foam roller. - Strengthen Postural Muscles

Focus on exercises that activate the mid-back and deep neck stabilizers:- Rows (band or dumbbell)

- Face pulls

- Prone Y-T-W raises

- Dead bugs and bird-dogs for core stability

- Practice Mindful Alignment

Set hourly reminders to check in with your posture. Ask: Are my ears over my shoulders? Is my ribcage stacked above my pelvis? - Gradually Reduce Device Use

If using a corrector, taper usage weekly as your natural control improves. Aim to rely on it less each week.

Real-World Example: Sarah’s Posture Journey

Sarah, a 34-year-old software developer, began experiencing neck stiffness and fatigue after transitioning to remote work. She bought a popular posture corrector online and wore it 6–8 hours daily, believing it would “retrain” her body. After three weeks, she noticed her symptoms returned immediately when she took it off—and her upper back felt weaker.

She consulted a physical therapist who explained the risk of dependency. Together, they designed a plan: wear the brace only for two hours in the afternoon, paired with daily exercises including scapular retractions, chin tucks, and thoracic rotations. Within six weeks, Sarah could maintain upright posture unaided and discontinued the device entirely.

Her success wasn’t due to the brace—it was due to replacing passive support with active engagement.

Comparison: Effective vs. Ineffective Use of Posture Correctors

| Factor | Effective Use | Ineffective Use |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 2–4 hours/day, gradually reduced | 8+ hours/day, constant wear |

| Exercise Integration | Paired with strength & mobility work | No additional movement practice |

| User Goal | Relearn proper alignment | Relieve pain permanently via bracing |

| Muscle Engagement | Encourages active stabilization | Promotes passive reliance |

| Long-Term Outcome | Sustained postural improvement | Dependency and regression |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can posture correctors make my posture worse?

Yes, if used excessively. Prolonged reliance can inhibit the very muscles needed for natural posture, leading to weakening over time. Without active training, the body may become dependent on external support, worsening slouching when the device is removed.

How long should I wear a posture corrector each day?

Begin with 15–30 minutes and gradually increase to no more than 2–4 hours daily. Never wear it while sleeping or during intense physical activity. The goal is sensory feedback, not constant correction.

Are there any people who should avoid posture correctors?

Individuals with respiratory conditions (like COPD), skin sensitivities, or certain spinal injuries should consult a healthcare provider before use. Pregnant women and those with pacemakers should also exercise caution. Always prioritize medical advice over commercial product claims.

Action Plan: Building Posture Resilience Without Dependency

If you’re considering a posture corrector—or already using one—follow this checklist to ensure it supports, rather than hinders, your progress.

- ✅ Use only as a biofeedback tool, not a permanent solution

- ✅ Limit wear to 2–4 hours per day maximum

- ✅ Combine with daily strengthening exercises (rows, face pulls, etc.)

- ✅ Practice posture awareness without the device

- ✅ Schedule regular breaks from sitting every 30–60 minutes

- ✅ Reassess progress monthly—can you maintain posture without the brace?

- ✅ Consult a physical therapist if pain persists beyond 2–3 weeks

Conclusion: Posture Is Earned Through Movement, Not Forced by Devices

Posture correctors are neither miracle cures nor useless gadgets. They occupy a middle ground: potentially helpful tools when used strategically, but risky crutches when relied upon passively. The real fix for slouching isn’t strapping your shoulders back—it’s rebuilding the strength, flexibility, and neuromuscular control that allow your body to hold itself upright naturally.

Think of posture not as a static position, but as a dynamic skill—one that improves with practice, awareness, and consistent effort. Devices may offer a starting point, but lasting change comes from movement, mindful habits, and functional strength.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?