Back pain affects millions of people worldwide, often stemming from prolonged sitting, poor ergonomics, or muscle imbalances caused by slouching. As a result, posture correctors—brace-like devices designed to pull shoulders back and align the spine—have surged in popularity. Marketed as quick fixes for chronic discomfort, they promise improved posture and reduced pain. But do they actually deliver lasting benefits, or are they just temporary props that mask deeper issues? The answer isn’t straightforward, but understanding how they work, their limitations, and how to use them effectively can clarify whether they’re worth incorporating into a long-term pain management strategy.

How Posture Correctors Work

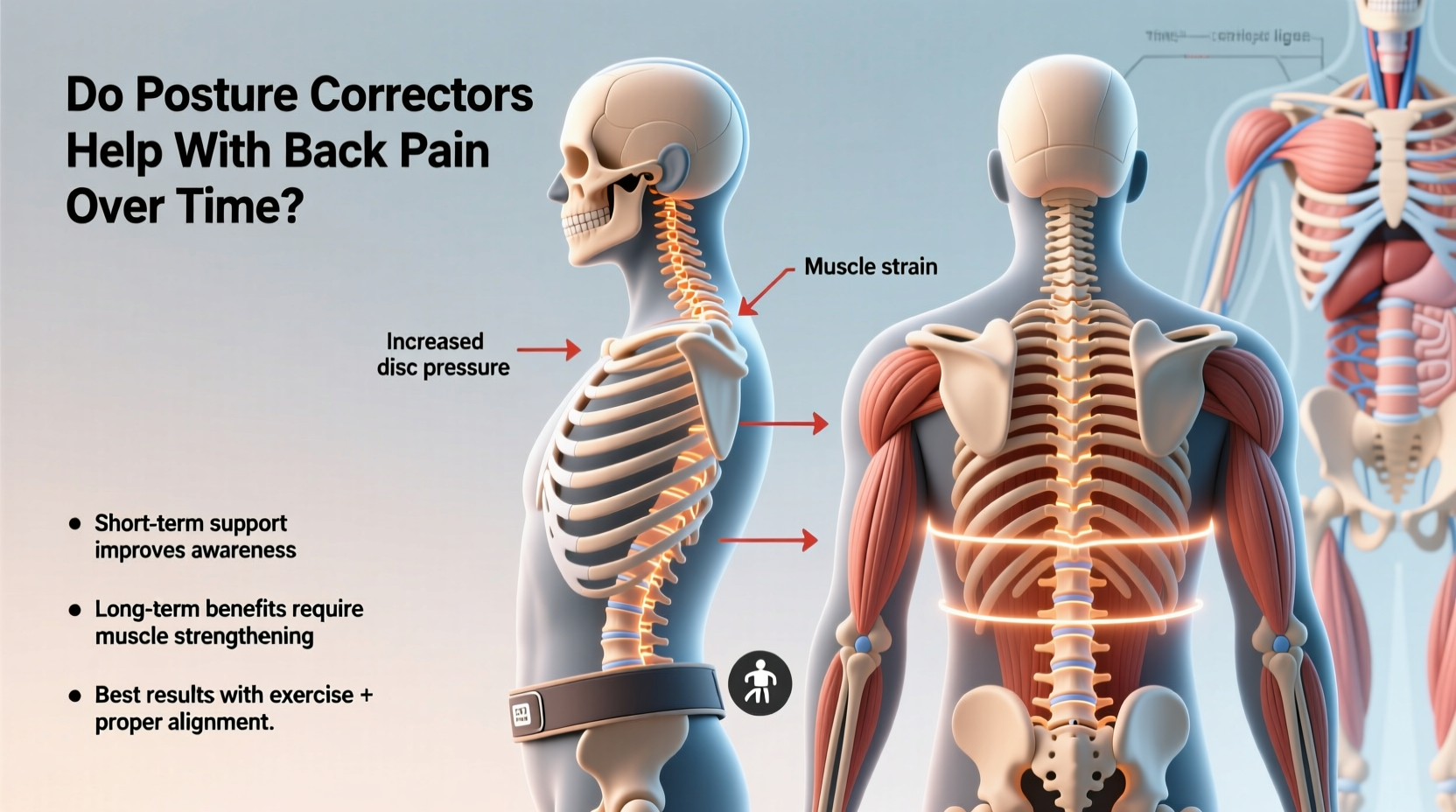

Posture correctors typically consist of adjustable straps worn across the shoulders and upper back, sometimes anchored around the arms or chest. Their primary function is mechanical: they physically restrict forward shoulder rounding and encourage spinal extension. By gently pulling the shoulders into retraction, these devices aim to train the body into a more neutral alignment.

The theory behind their use rests on neuromuscular re-education—the idea that repeated positioning helps the brain and muscles “remember” proper posture. Over time, users may become more aware of their postural habits and maintain better alignment even without the device.

However, this mechanism only addresses the symptom—poor posture—not the root causes of back pain, such as weak core muscles, tight hip flexors, or disc degeneration. Without addressing these underlying factors, reliance on a posture corrector may offer short-term relief but limited long-term improvement.

The Science Behind Posture and Back Pain

Poor posture—specifically forward head position, rounded shoulders, and increased thoracic kyphosis—is frequently associated with musculoskeletal pain, particularly in the neck, upper back, and shoulders. A 2020 study published in the Journal of Physical Therapy Science found that individuals with chronic upper back pain showed significant improvements in pain scores after four weeks of combined posture correction exercises and ergonomic adjustments.

However, research specifically on wearable posture correctors is limited and mixed. A randomized controlled trial from 2018 in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies concluded that while participants reported immediate comfort and perceived postural improvement when using a brace, there was no significant difference in actual spinal alignment or pain reduction after six weeks compared to a control group doing only postural exercises.

This suggests that while posture correctors may provide sensory feedback and psychological reassurance, they don’t inherently strengthen muscles or correct biomechanical dysfunction. Real change requires active engagement—strengthening postural muscles like the rhomboids, lower trapezius, and deep neck flexors—rather than passive support.

“Devices can guide posture, but lasting improvement comes from neuromuscular control and muscle endurance. You can’t brace your way to good posture.” — Dr. Lena Patel, DPT, Board-Certified Orthopedic Specialist

Benefits and Limitations of Long-Term Use

When used appropriately, posture correctors can play a supportive role in a broader rehabilitation plan. However, relying on them exclusively—or for extended periods—can lead to unintended consequences.

Benefits

- Immediate feedback: Helps users recognize when they’re slouching.

- Pain relief during flare-ups: Can reduce strain on overworked upper back muscles.

- Habit formation: May assist in building initial awareness of posture during daily tasks.

- Workplace support: Useful for desk workers needing reminders to sit upright during long hours.

Limitations and Risks

- Muscle atrophy: Prolonged use may weaken postural muscles due to dependency.

- Skin irritation: Constant friction or pressure can cause chafing or discomfort.

- False sense of progress: Users may feel “fixed” without making real biomechanical changes.

- Inadequate for structural issues: Won’t correct scoliosis, herniated discs, or joint degeneration.

| Aspect | Short-Term Use (1–4 weeks) | Long-Term Use (Beyond 6 weeks) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain Relief | Often effective due to reduced muscular strain | Diminishes if underlying weakness persists |

| Postural Awareness | Significantly improved with consistent wear | May decline if not paired with habit training |

| Muscle Engagement | Can complement strengthening routines | Risk of disengagement and weakening |

| Risk of Dependency | Low when used part-time | High with full-day, continuous use |

Building Sustainable Posture: A Step-by-Step Approach

If you're considering a posture corrector, treat it as one component of a comprehensive strategy—not a standalone solution. Lasting relief from back pain comes from consistent, active effort. Follow this timeline to integrate healthy posture habits sustainably:

- Week 1–2: Assess and Introduce

Identify when and where your posture deteriorates (e.g., working at a desk, driving). Begin wearing the corrector for 20–30 minutes twice daily while performing mindful posture drills. - Week 3–4: Combine with Exercise

Add simple strengthening exercises: rows with resistance bands, chin tucks, scapular retractions. Perform 3 sets of 10 reps, three times per week. - Week 5–6: Reduce Device Use

Wear the corrector only when needed (e.g., during long meetings). Focus on maintaining alignment without assistance. - Week 7+: Evaluate Progress

Track pain levels and posture awareness. If pain persists, consult a physical therapist. Discontinue device use if no functional improvement is seen.

This phased approach emphasizes self-reliance and builds intrinsic strength. The goal is to make proper posture automatic, not something enforced by external gear.

Real-World Example: Office Worker with Chronic Upper Back Pain

Mark, a 38-year-old software developer, began experiencing persistent upper back and neck pain after transitioning to remote work. His home office setup lacked ergonomic support, and he spent 9–10 hours daily hunched over his laptop. After trying over-the-counter painkillers with little relief, he purchased a popular posture corrector online.

Initially, Mark felt immediate improvement—he sat taller, and the sharp pain between his shoulder blades subsided. Encouraged, he wore the brace for 6–8 hours daily. However, after five weeks, the pain returned, and he noticed discomfort in his chest and underarms from constant strap pressure.

He consulted a physical therapist, who assessed muscle weakness in his mid-back and tightness in his pectorals. The therapist advised him to stop full-time use of the corrector and instead prescribed targeted exercises and ergonomic adjustments. Within eight weeks of consistent therapy—including wall angels, prone T/Y raises, and workstation modifications—Mark’s pain decreased significantly, and he no longer needed the brace.

His experience illustrates a common pitfall: mistaking symptomatic relief for curative treatment. The corrector helped initially, but only active rehabilitation produced lasting results.

Expert Recommendations and Best Practices

Healthcare professionals agree that posture correctors should be used cautiously and strategically. Here are key guidelines based on clinical best practices:

- Use as a cue, not a crutch: Wear for short intervals to build awareness, then remove to practice holding the position independently.

- Pair with movement: Combine use with stretching tight muscles (chest, neck) and strengthening weak ones (upper back, core).

- Avoid sleeping or exercising in them: These devices are not designed for dynamic activity or rest.

- Adjust fit properly: Straps should be snug but not restrictive; red marks or numbness indicate improper use.

- Listen to your body: If pain worsens or new discomfort arises, discontinue use immediately.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can posture correctors fix scoliosis?

No. Scoliosis involves a lateral curvature of the spine and requires medical evaluation and specialized treatment, such as bracing (different from consumer posture correctors), physical therapy, or surgery. Standard posture braces do not correct structural spinal deformities.

How many hours a day should I wear a posture corrector?

Start with 20–30 minutes, 1–2 times per day. Gradually increase only if comfortable, but avoid exceeding 2 hours total daily. Long-term daily use is not recommended due to risk of muscle dependency.

Are there alternatives to posture correctors?

Yes. Effective alternatives include ergonomic workspace setup, regular posture-check routines, yoga, Pilates, and guided physical therapy. Mirror feedback, posture apps with motion sensors, and foam rolling can also enhance body awareness without wearing a brace.

Final Thoughts: A Tool, Not a Cure

Posture correctors can offer temporary relief and serve as useful biofeedback tools for individuals beginning their journey toward better spinal health. They may help break the cycle of slouching and create momentary comfort for those with mild postural strain. However, they are not a substitute for active rehabilitation, strength training, or ergonomic optimization.

For long-term back pain reduction, the focus must shift from external support to internal resilience. Building strong postural muscles, correcting lifestyle habits, and addressing environmental contributors like poorly designed workspaces yield far greater and more sustainable outcomes.

If you're struggling with persistent back pain, consider consulting a physical therapist or chiropractor for a personalized assessment. They can determine whether your pain is postural, structural, or a combination—and guide you toward evidence-based solutions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?