Have you ever watched someone wiggle their ears and wondered how they do it? Or perhaps you’ve tried and realized yours barely budge. Ear wiggling may seem like a quirky party trick, but it’s actually rooted in human anatomy, evolution, and neuromuscular control. While only about 10–20% of people can voluntarily move their ears, the ability—or lack thereof—reveals fascinating insights into our biology.

This phenomenon isn’t just random; it’s influenced by genetics, muscle development, and even evolutionary history. Some people can lift, lower, or twitch one or both ears independently. Others can’t move them at all. Understanding why requires a closer look at the muscles involved, the role of natural selection, and whether this skill can be learned.

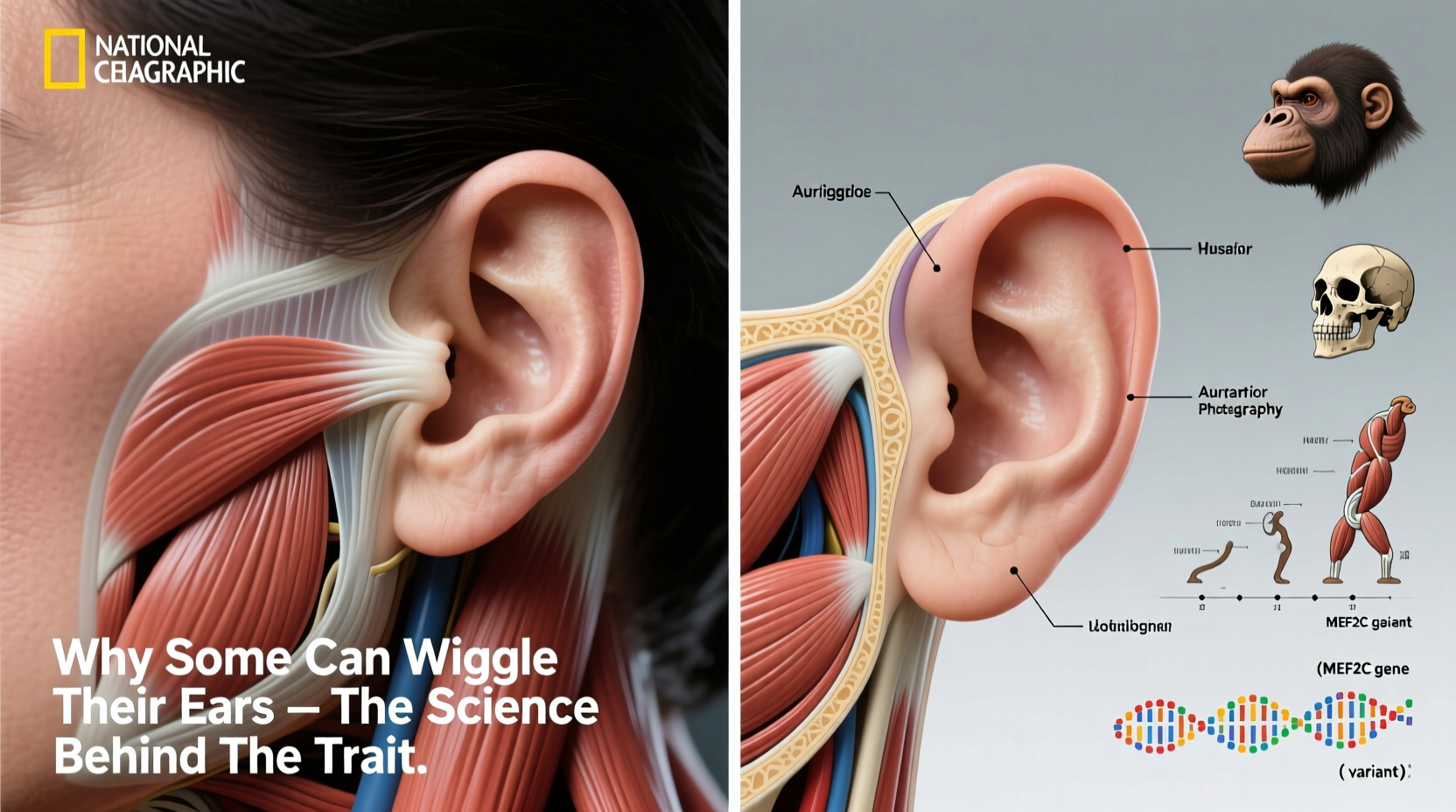

The Anatomy Behind Ear Movement

Human ears are equipped with a set of small, underdeveloped muscles known as the auricular muscles. These include the anterior, superior, and posterior auriculares, which attach to the outer ear (the pinna) and originate from the skull. In animals like cats, dogs, and horses, these muscles are highly functional, allowing precise directional hearing by rotating the ears toward sounds.

In humans, however, most of these muscles are vestigial—meaning they’ve lost much of their original function through evolution. While we retain the anatomical structures, neural signals to control them have diminished over time. That said, some individuals still possess enough neuromuscular coordination to activate these muscles voluntarily.

Electromyography (EMG) studies show that even people who cannot visibly move their ears often exhibit faint electrical activity in the auricular muscles when focusing on the task. This suggests latent potential exists in many, though full control remains rare.

“While ear wiggling seems trivial, it reflects a deeper story of human evolution and the persistence of ancient reflexes.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Neuroanatomist, University of Edinburgh

Evolutionary Origins of Ear Mobility

Our distant ancestors likely had mobile ears similar to modern primates and other mammals. The ability to orient the ears toward sounds would have been crucial for detecting predators or prey in dense environments. Over millions of years, as vision became the dominant sense and social communication evolved, reliance on acute directional hearing decreased.

Natural selection gradually favored traits like complex facial expressions and vocal communication over physical ear movement. As a result, the brain’s motor cortex devoted less space to controlling auricular muscles. Today, only a fraction of the population retains sufficient neural wiring to consciously manipulate these muscles.

Interestingly, some research indicates that people who can wiggle their ears also tend to have stronger eyebrow mobility. This correlation may stem from shared developmental pathways in cranial nerve VII (the facial nerve), which controls many facial muscles, including those near the ears and eyebrows.

Genetics and Individual Variation

Can ear wiggling be inherited? Evidence suggests yes. Studies dating back to the early 20th century observed familial patterns in auricular mobility. If one parent can wiggle their ears, there’s a higher likelihood their children can too—though not guaranteed.

A 1949 study published in the Journal of Heredity found that among families where one parent could move their ears, approximately 58% of offspring demonstrated some degree of ear mobility. When neither parent could do it, only 7% of children could. This points to a possible autosomal dominant trait with incomplete penetrance—meaning the gene is present but doesn’t always express itself.

However, genetics alone don’t tell the whole story. Neural plasticity, practice, and conscious effort play significant roles. Some individuals develop the ability later in life through deliberate training, suggesting that environmental factors and learning can override genetic predisposition to some extent.

Can You Learn to Wiggle Your Ears?

Yes—many people have successfully trained themselves to move their ears, even without prior ability. It requires patience, focus, and consistent practice. The process involves isolating and strengthening the auricular muscles using mental visualization and subtle facial movements.

Step-by-Step Guide to Training Ear Movement

- Find a mirror: Sit in front of a reflective surface where you can clearly see your ears.

- Relax your face: Start with a neutral expression to avoid engaging unrelated muscles.

- Attempt eyebrow lifts: Raise your eyebrows quickly and hold. Notice any slight upward pull near the ears.

- Focus behind the ears: Try to “scrunch” the skin just behind the top of each ear. This often activates the posterior auricular muscle.

- Combine motions: Attempt to lift your eyebrows while simultaneously pulling the ears forward or backward.

- Practice daily: Spend 5–10 minutes per day experimenting. Progress may take weeks or months.

Success varies widely. Some report minor twitches within days; others never achieve visible movement despite months of effort. Those who succeed often describe a sensation similar to “flexing an invisible muscle” behind the ear.

Common Myths and Misconceptions

- Myth: Only men can wiggle their ears. Reality: Both genders can, though some older studies suggested slightly higher prevalence in males—likely due to sampling bias.

- Myth: Ear wiggling improves hearing. Reality: There’s no evidence it enhances auditory perception in humans.

- Myth: It's a sign of intelligence. Reality: No scientific link exists between cognitive ability and ear mobility.

| Factor | Contribution to Ear Wiggling Ability |

|---|---|

| Genetics | High – family history increases likelihood |

| Neuromuscular Control | High – brain’s ability to isolate ear muscles |

| Facial Muscle Coordination | Moderate – linked to eyebrow and scalp movement |

| Practice & Training | Moderate to High – possible improvement with repetition |

| Age | Low – ability typically develops in childhood, but training works at any age |

Real Example: From Inability to Mastery

James, a 28-year-old software developer from Portland, couldn’t move his ears at all until he stumbled upon a forum post about self-training. Intrigued, he began practicing during short breaks at work. He started by mimicking cat ear movements in the mirror, combining eyebrow raises with subtle head tilts.

After three weeks of daily 5-minute sessions, he noticed a tiny flicker in his left ear. By week six, he could lift both ears slightly. Now, eight months later, he can wiggle each ear independently—a skill he demonstrates at parties and team meetings to break the ice. “It felt impossible at first,” he says, “but persistence paid off. It’s like discovering a hidden feature in your own body.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Can everyone learn to wiggle their ears?

Not necessarily. While many can improve muscle awareness and achieve minor movements, full, controlled wiggling may remain out of reach for some due to anatomical or neurological limitations.

Is ear wiggling related to other facial tics?

No. Voluntary ear wiggling is a controlled motor skill, not a tic. However, some people with conditions like hemifacial spasm may experience involuntary ear twitching, which is medically distinct.

Do babies have better ear movement than adults?

Some infants display reflexive ear movements in response to sounds, suggesting residual primitive reflexes. These usually disappear within the first year and don’t predict future voluntary control.

Practical Tips for Developing Ear Control

- Use a mirror to provide visual feedback.

- Record yourself occasionally to track progress.

- Avoid tensing your jaw or neck—focus only on the ear area.

- Pair the movement with a mental cue, like imagining your ears are satellite dishes turning toward a signal.

- Stay patient. Neuromuscular retraining takes time.

Conclusion: Embrace the Quirk

Whether you can wiggle your ears or not, the ability offers a unique window into human evolution and individual variation. For those who can, it’s a fun demonstration of neuromuscular precision. For those who can’t, it’s a reminder that our bodies still carry traces of ancient survival mechanisms—even if they’re now used for amusement rather than alertness.

And if you’ve ever wanted to try, now you know it’s not entirely out of reach. With focused practice, you might unlock a hidden talent buried deep in your anatomy. Whether you succeed or not, the journey reveals something profound: the human body is full of surprises, many of which lie just beneath the surface of awareness.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?