Understanding how to substitute fresh herbs for dried—and vice versa—is one of the most essential skills in home cooking. A dish can shift from vibrant and aromatic to dull or overpowering based solely on which form of herb is used and in what quantity. While both fresh and dried herbs bring depth and character to food, they are not interchangeable by volume alone. Misjudging the ratio can result in underseasoned soups or unexpectedly pungent sauces. This guide clarifies the science and art behind herb conversions, explains when to use each type, and offers professional techniques for maximizing flavor, preserving quality, and avoiding common mistakes.

Definition & Overview

Herbs are the leafy, green parts of aromatic plants used to enhance the flavor, aroma, and visual appeal of food. Unlike spices—which come from seeds, bark, roots, or fruit—herbs contribute bright, often grassy, floral, or citrusy notes. Common culinary herbs include basil, thyme, rosemary, oregano, parsley, cilantro, dill, and tarragon.

These herbs are available in two primary forms: fresh and dried. Fresh herbs are harvested at peak maturity and used shortly thereafter, retaining their moisture, volatile oils, and delicate textures. Dried herbs undergo dehydration, either naturally or through mechanical means, concentrating certain compounds while diminishing others. The drying process fundamentally alters the chemical profile, resulting in a more subdued aroma but intensified earthiness in some cases.

The choice between fresh and dried is not merely logistical—it affects taste, texture, timing, and technique. Knowing how and when to use each ensures consistency and balance in every dish.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Fresh Herbs | Dried Herbs |

|---|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Bright, grassy, citrusy, floral; nuanced and layered | Earthy, concentrated, sometimes musty; less volatile top notes |

| Aroma | Immediate, fragrant, volatile (releases quickly) | Muted; requires heat or rehydration to release fully |

| Texture | Crisp, tender, sometimes fibrous stems | Brittle, crumbly, papery |

| Color | Vibrant green (varies by herb) | Faded green to brownish; loss of chlorophyll |

| Shelf Life | 3–14 days refrigerated | 6–18 months stored properly |

| Culinary Function | Finisher, garnish, raw applications, late-addition seasoning | Early seasoning, long-cooked dishes, marinades, dry rubs |

Practical Usage: How to Use Each Form

Fresh and dried herbs serve different roles in cooking due to their physical and chemical differences. Their application depends on the dish’s cooking time, desired flavor intensity, and final presentation.

Fresh Herbs: When and How to Use

- Add at the end of cooking: Heat degrades delicate volatile oils. Basil in tomato sauce, cilantro in salsa, or dill in yogurt should be stirred in just before serving.

- Use in raw preparations: Pesto, chimichurri, gremolata, herb salads, and dressings rely on the crispness and freshness of uncooked herbs.

- Chop finely for even distribution: Tender leaves like parsley or chives benefit from a fine mince; woody-stemmed herbs like rosemary should have leaves stripped and chopped separately.

- Garnish with intention: A sprig of mint on a cocktail or flat-leaf parsley over grilled fish adds color and a burst of aroma.

Dried Herbs: When and How to Use

- Add early in cooking: Dried herbs need time and moisture to rehydrate and release their flavor. Add them during sautéing or within the first 10–15 minutes of simmering.

- Crush between fingers before use: This breaks cell walls and releases trapped essential oils, enhancing potency.

- Ideal for long-simmered dishes: Stews, braises, curries, soups, and bean dishes benefit from the slow infusion of dried oregano, thyme, or marjoram.

- Use in dry rubs and spice blends: Dried herbs integrate seamlessly into rubs for meats, poultry, or roasted vegetables.

Pro Tip: For dishes that combine both forms—like a slow-cooked lamb tagine with a fresh herb garnish—use dried herbs during cooking for depth and fresh herbs at the end for brightness. This layering technique mimics restaurant-level complexity.

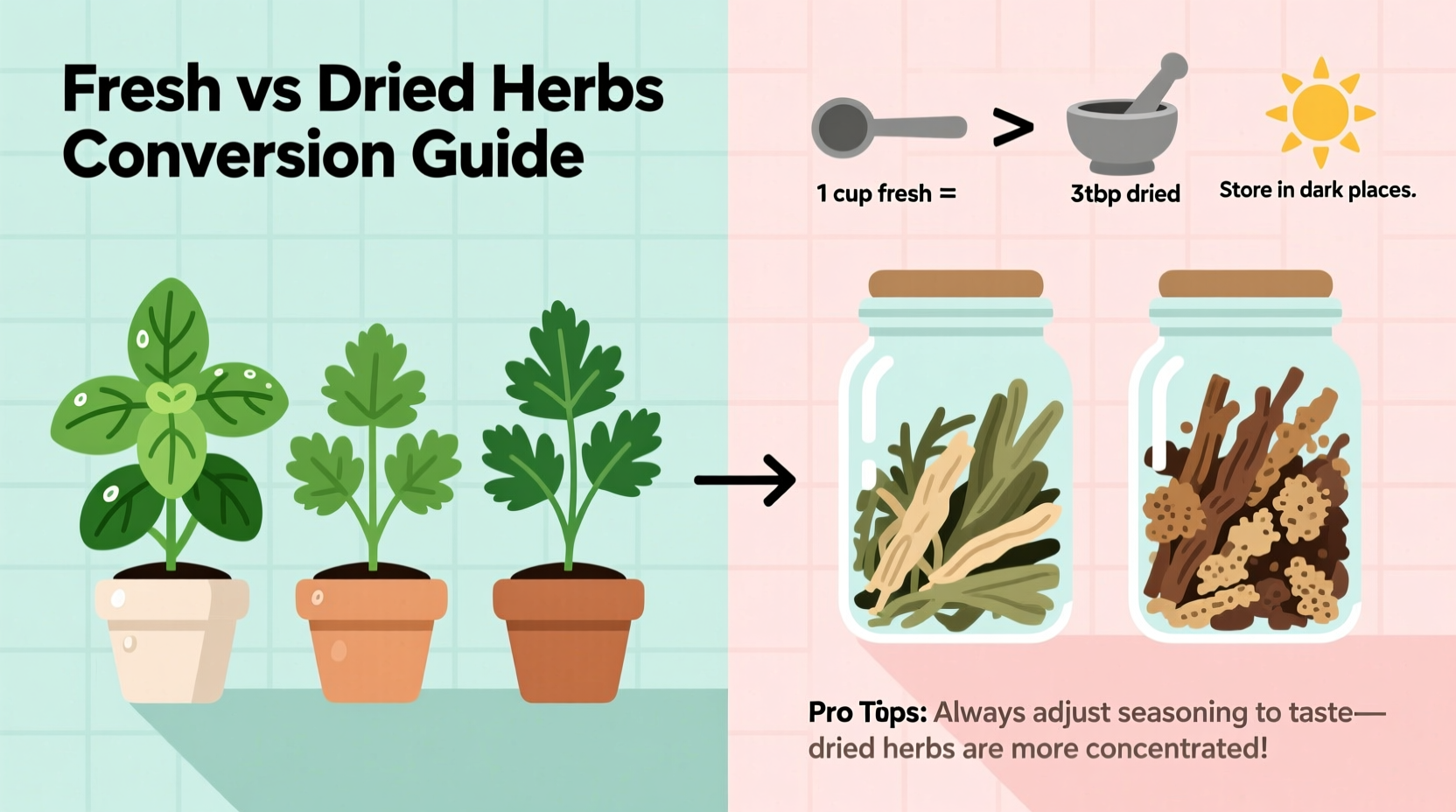

Conversion Guide: Fresh to Dried and Back

The standard conversion ratio between fresh and dried herbs is 3:1. Because dried herbs are more concentrated (having lost water weight), you need less of them to achieve similar flavor impact.

- For every 1 tablespoon of fresh chopped herbs, use 1 teaspoon of dried herbs.

- For every 1 teaspoon of dried herbs, use 1 tablespoon of fresh herbs.

This rule applies to most soft-leaved herbs such as basil, oregano, thyme, marjoram, savory, and dill. However, exceptions exist:

- Parsley and cilantro: These lose significant flavor when dried. Rehydrated dried parsley lacks the crisp freshness needed in tabbouleh or chimichurri. Substitution is not recommended unless absolutely necessary.

- Tarragon and chervil: Highly volatile; drying diminishes their anise-like nuance. Use fresh whenever possible.

- Rosemary and sage: Woody herbs retain more flavor when dried. In fact, dried rosemary may be preferable in long-cooked dishes where prolonged exposure would make fresh rosemary overly sharp.

Always adjust to taste. Recipes provide guidance, but personal preference and ingredient quality matter. A potent batch of home-dried oregano may require only half the suggested amount.

Variants & Types of Dried Herbs

Not all dried herbs are created equal. Understanding the types helps ensure optimal results:

1. Air-Dried (Sun or Shade-Dried)

Naturally dehydrated without heat. Preserves more essential oils than oven-drying. Best for delicate herbs like basil and dill. Often sold in specialty stores or grown at home.

2. Oven- or Dehydrator-Dried

Faster method using controlled heat. Can reduce volatile oils if temperature exceeds 95°F (35°C). Ideal for hardy herbs like thyme, oregano, and rosemary.

3. Freeze-Dried

Commercial process that removes moisture via sublimation. Retains color, shape, and flavor better than traditional drying. Found in premium spice brands. More expensive but closer to fresh in performance.

4. Ground vs. Whole Leaf

Ground dried herbs (e.g., powdered basil) have greater surface area and release flavor faster but degrade more quickly. Whole leaf versions preserve flavor longer and are better for long simmers where gradual infusion is desired.

Home Drying Tip: Hang small bunches of herbs upside down in a warm, dark, well-ventilated space for 7–10 days. Store in airtight glass jars away from light. Label with date and herb type. Properly stored, they last up to a year.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Confusion often arises between herbs, spices, and related plant parts. Clarifying these distinctions improves accuracy in substitution and usage.

| Item | True Category | Common Confusion | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bay leaf | Dried herb (laurel) | Mistaken for a spice due to its use in slow cooking | Used whole and removed; imparts subtle bitterness and depth |

| Cilantro leaves vs. coriander seeds | Leaves = herb; seeds = spice | Same plant, entirely different flavor profiles | Cilantro is citrusy and polarizing; coriander seeds are warm, nutty, sweet |

| Green vs. dried thyme | Fresh vs. dried form of same herb | Assumed to be interchangeable by volume | Fresh has milder, floral notes; dried is earthier and stronger per gram |

| Mint varieties (spearmint, peppermint) | Herbs | Assumed to be interchangeable | Spearmint is sweeter, better for food; peppermint is menthol-heavy, best for tea/desserts |

Practical Tips & FAQs

Q: Can I substitute dried herbs for fresh in pesto?

A: Not effectively. Pesto relies on the oil-emulsifying properties and fresh texture of raw basil, pine nuts, garlic, and Parmesan. Dried basil lacks moisture and vibrancy, resulting in a flat, dusty paste. If fresh basil is unavailable, consider a sun-dried tomato or roasted red pepper spread as an alternative, rather than forcing a flawed substitution.

Q: Why does my stew taste bitter when I use dried herbs?

A: Overuse or improper timing. Dried herbs become more assertive over time. Adding too much or introducing them too late in cooking prevents proper integration. Always start with half the recommended amount, especially with potent herbs like oregano or rosemary, and adjust after 20–30 minutes of simmering.

Q: How do I store fresh herbs to extend shelf life?

A: Treat them like cut flowers. Trim stems, place in a glass with 1–2 inches of water, and cover loosely with a plastic bag. Refrigerate (except basil, which prefers room temperature away from direct sun). Change water every two days. Alternatively, wrap in slightly damp paper towels and store in airtight containers.

Q: Do dried herbs lose potency over time?

A: Yes. Dried herbs degrade due to exposure to light, heat, oxygen, and humidity. They don’t spoil but lose aromatic compounds. Test potency by crushing a small amount and smelling it. If the scent is faint or musty, replace it. Most dried herbs retain peak quality for 6–12 months.

Q: Are organic dried herbs worth the extra cost?

A: Often, yes. Herbs are prone to pesticide residue, especially when imported. Organic certification ensures cleaner sourcing. Additionally, many premium organic brands use fresher stock and better post-harvest handling, leading to superior flavor and aroma.

Q: Can I freeze fresh herbs?

A: Absolutely. Chop herbs, place in ice cube trays, cover with water or olive oil, and freeze. Ideal for herbs like parsley, chives, or cilantro used in cooked dishes. Thaw before use. Note: frozen herbs lose structural integrity and are unsuitable for garnish but excellent for soups, sauces, and stews.

Q: What’s the best herb for beginners to grow at home?

A: Basil, mint, or thyme. These are resilient, fast-growing, and forgiving. Even apartment dwellers can maintain a windowsill pot. Homegrown herbs offer peak freshness and eliminate waste from unused store-bought bunches.

Expert Insight: \"I always keep dried thyme and oregano on hand for winter braises, but I never dry my own rosemary. The home-dried version turns too sharp. I’d rather buy high-quality dried rosemary from a reputable spice merchant who controls the drying process.\" — Clara Nguyen, Executive Chef, Hearth & Vine

Summary & Key Takeaways

Mastering the use of fresh and dried herbs elevates everyday cooking. The core principles are simple but profound:

- Use the 3:1 ratio—1 tablespoon fresh equals 1 teaspoon dried—as a starting point, then adjust to taste.

- Add fresh herbs late, typically in the final minutes of cooking or as a garnish, to preserve aroma and color.

- Add dried herbs early to allow rehydration and full flavor development, especially in moist, long-cooked dishes.

- Store both forms properly: fresh herbs in water or damp cloth in the fridge; dried herbs in airtight, dark glass jars in a cool, dry place.

- Know the exceptions: Some herbs like parsley, cilantro, and tarragon lose too much character when dried and should be used fresh when possible.

- Layer flavors in complex dishes by using dried herbs during cooking and fresh herbs at the end for dimension.

Ultimately, the choice between fresh and dried is not about superiority—it’s about context. A rustic Italian ragù benefits from the deep, resinous notes of dried oregano, while a Vietnamese pho shines with the bright lift of fresh Thai basil and cilantro. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each form, home cooks gain precision, confidence, and creative control.

Take action today: Open your spice cabinet and check the dates on your dried herbs. Crush a pinch of thyme or oregano between your fingers. If the aroma is weak, replace them. Then, pick one dish this week to refine using the 3:1 conversion rule. Notice the difference.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?