Heat is one of the most dynamic and polarizing elements in cooking. While some diners crave the searing thrill of a habanero-laced salsa, others flinch at the mere suggestion of black pepper in excess. The difference lies not just in personal tolerance but in understanding how spice works—where it comes from, how it's measured, and how to wield it with precision. For home cooks and culinary professionals alike, mastering spice heat levels transforms recipes from hit-or-miss experiments into controlled, flavorful experiences. This guide demystifies the science, measurement, and application of chili heat, equipping you with the knowledge to balance fire and flavor confidently.

Definition & Overview: What Is Spice Heat?

Spice heat—commonly referred to as \"pungency\" or \"piquancy\"—is the sensation of burning or warmth produced primarily by compounds in chili peppers known as capsaicinoids. The most prominent of these is capsaicin, which binds to pain receptors (TRPV1) in the mouth, nose, and skin, triggering a neurological response interpreted as heat. Unlike actual temperature, this sensation is chemical, not thermal, meaning no physical rise in temperature occurs. Capsaicin is concentrated in the placental tissue (the white ribs and seeds) of chili peppers, though it disperses throughout the flesh during cooking.

The use of spicy ingredients spans nearly every global cuisine, from the fiery curries of Sichuan China to the smoky heat of Mexican chiles de árbol. However, cultural context shapes both tolerance and application. In regions where chilies have been dietary staples for centuries, populations often exhibit higher thresholds for heat due to habitual exposure. Elsewhere, heat may be used more sparingly, as an accent rather than a foundation.

Key Characteristics of Chili Heat

- Primary Compound: Capsaicin (and related capsaicinoids like dihydrocapsaicin)

- Sensation Type: Neurological irritation perceived as heat or burning

- Onset Time: Immediate to delayed, depending on form and preparation

- Persistence: Can linger for minutes; mitigated by fats, dairy, or sugars

- Heat Distribution: Concentrated in pepper membranes and seeds; less in flesh

- Solubility: Fat-soluble, not water-soluble—water can spread the burn

- Shelf Life of Dried Chilies: Up to 1–2 years when stored properly; potency fades over time

Tip: Always handle fresh hot chilies with care. Wear gloves when seeding or chopping, and avoid touching your face. Wash hands thoroughly with soap afterward—even residual oils can cause discomfort later.

Measuring Heat: The Scoville Scale and Beyond

The most widely recognized method for quantifying chili heat is the Scoville Organoleptic Test, developed in 1912 by pharmacist Wilbur Scoville. Originally, it involved diluting chili extract in sugar water until the heat was no longer detectable by a panel of tasters. The degree of dilution determined the Scoville Heat Units (SHU). A bell pepper measures 0 SHU, while a jalapeño ranges from 2,500 to 8,000 SHU—meaning its extract must be diluted 2,500 times before the heat disappears.

While historically significant, the organoleptic method is subjective. Modern laboratories now use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to measure capsaicinoid concentration precisely, then convert the results to Scoville units using a mathematical formula. This method is objective, repeatable, and far more accurate.

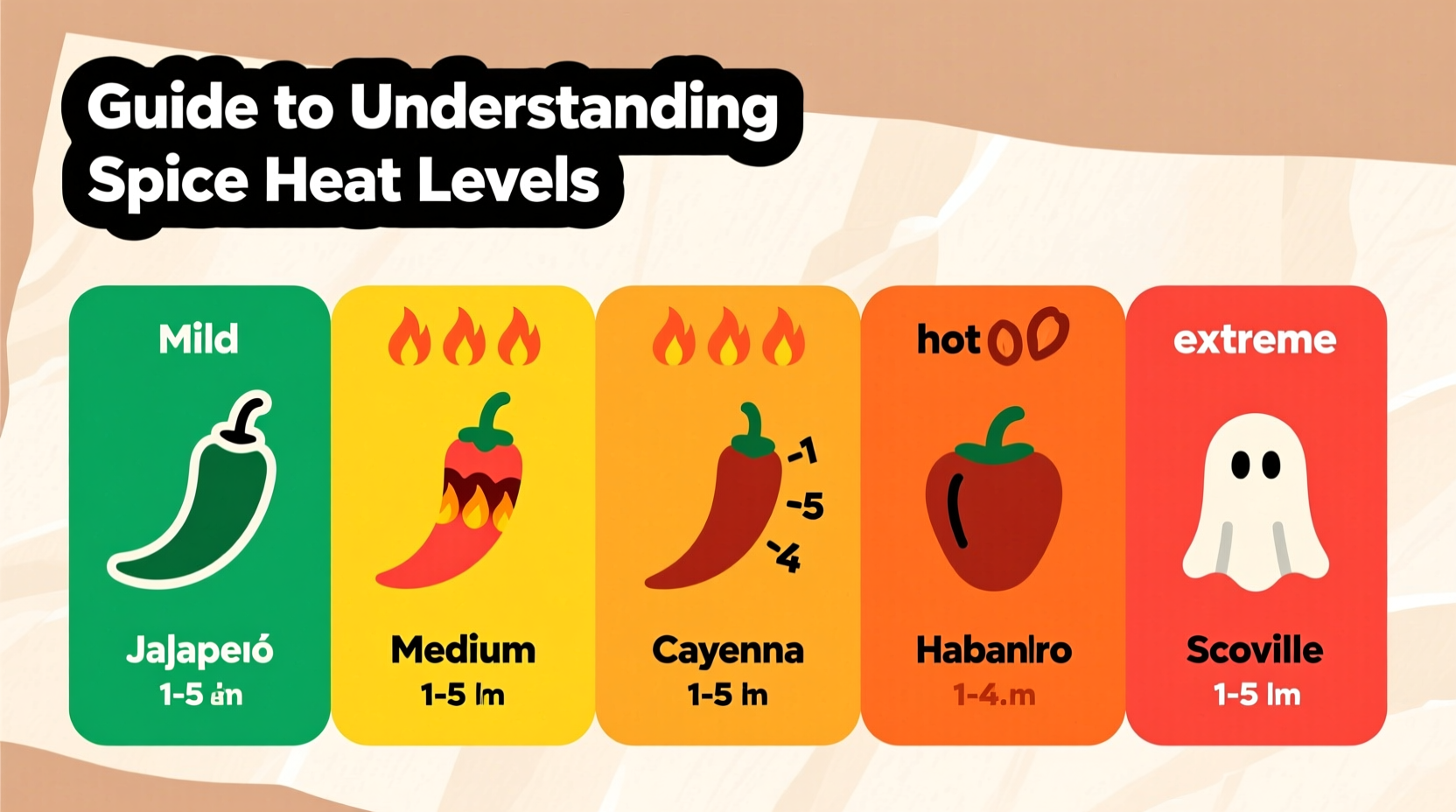

Common Chilies and Their Scoville Ratings

| Chili Variety | Scoville Heat Units (SHU) | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Bell Pepper | 0 | Sweetness, crunch, color |

| Poblano | 1,000–2,000 | Stuffed peppers, mole, roasted dishes |

| Jalapeño | 2,500–8,000 | Salsas, nachos, pickled preparations |

| Serrano | 10,000–23,000 | Fresh salsas, guacamole, garnishes |

| Cayenne | 30,000–50,000 | Spice blends, sauces, soups |

| Thai Bird’s Eye Chili | 50,000–100,000 | Thai curries, stir-fries, dipping sauces |

| Habanero | 100,000–350,000 | Caribbean sauces, hot sauces, marinades |

| Ghost Pepper (Bhut Jolokia) | 800,000–1,041,427 | Extreme heat challenges, specialty sauces |

| Carolina Reaper | 1,400,000–2,200,000 | World-record heat, experimental cooking |

\"The Scoville scale isn’t just about bragging rights—it’s a practical tool for predicting impact. Knowing that a habanero is ten times hotter than a jalapeño helps chefs scale recipes without incinerating palates.\" — Chef Elena Ruiz, Culinary Instructor, Institute of Latin American Cuisine

Variants & Types: Fresh, Dried, Powdered, and Extracts

Chili peppers appear in multiple forms, each altering heat perception, flavor complexity, and culinary function.

Fresh Chilies

Offer bright, vegetal notes with immediate heat. Best used raw in salsas or lightly cooked to preserve freshness. Examples: jalapeño, serrano, Thai chilies.

Dried Chilies

Concentrate heat and develop smoky, raisin-like depth. Rehydration or toasting unlocks complex flavors. Common types: ancho (dried poblano), guajillo, arbol, chipotle (smoked jalapeño).

Ground Spices & Flakes

Provide consistent dispersion of heat. Cayenne powder, crushed red pepper, and paprika vary widely in potency—always check labels. Freshly ground dried chilies offer superior aroma.

Liquid Extracts & Pure Capsaicin

Used in commercial hot sauces and extreme heat products. Products like pepper spray contain >2% capsaicin (over 1 million SHU). Not recommended for home use without protective gear.

Comparison of Forms and Heat Behavior

| Form | Relative Heat Level | Flavor Profile | Best Used In |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Moderate to high | Grassy, crisp, sometimes sweet | Raw applications, quick sautés |

| Dried | Higher concentration | Smoky, earthy, fruity | Stews, rubs, infused oils |

| Ground | Variable (check source) | Dusty, direct heat | Blends, batters, spice mixes |

| Liquid (hot sauce) | From mild to extreme | Acidic, fermented, vinegar-forward | Finishing, marinating, condiments |

Practical Usage: How to Use Spice Heat in Cooking

Effective use of heat requires more than adding chilies at random. It demands intentionality—knowing when to introduce heat, how much to use, and how to balance it with other tastes.

Step-by-Step: Building Balanced Heat

- Start Low, Taste Often: Begin with half the amount of chili you think you’ll need. You can always add more, but you can’t remove heat once it’s in.

- Control Release: Whole chilies infuse gradually; chopped or crushed release faster. Seeds and ribs increase intensity significantly.

- Layer Flavors: Toast dried chilies before grinding to deepen flavor. Bloom ground spices in oil to distribute heat evenly.

- Balance with Other Tastes: Sweetness (honey, fruit), acidity (lime, vinegar), salt, and fat (cream, coconut milk) all counteract heat. A squeeze of lime can rescue an overly spicy dish.

- Time Your Addition: Add delicate fresh chilies at the end. Use dried or powdered forms early in cooking to mellow their bite.

Pairing Suggestions by Cuisine

- Mexican: Pair serranos with tomatoes and cilantro in pico de gallo; use chipotle in adobo for smoky depth in braises.

- Thai: Combine bird’s eye chilies with lemongrass, galangal, and coconut milk in curries—the fat tempers the heat.

- Indian: Use cayenne or Kashmiri chili in garam masala blends. Kashmiri chili offers vibrant color with moderate heat.

- Southern U.S.: Crush red pepper flakes into gumbo or jambalaya. Balance with okra, which has mucilaginous properties that soothe heat.

- Caribbean: Scotch bonnet peppers are essential in jerk marinades—pair with allspice, thyme, and brown sugar for harmony.

Pro Tip: When adjusting a dish that’s too spicy, do not add more of the base ingredients. Instead, dilute with unsalted broth or coconut milk, or add bulk with potatoes or rice. A dollop of plain yogurt or sour cream cools the palate effectively.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Not all “heat” comes from capsaicin. Several ingredients produce pungency through different compounds, creating distinct sensations.

| Ingredient | Heat Source | Sensation | Neutralized By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chili Peppers | Capsaicin | Burning, lingering | Dairy, fats, starches |

| Black Pepper | Piperine | Sharp, brief warmth | Most foods |

| Horseradish / Wasabi | Allyl isothiocyanate | Nasal burn, fleeting | Time, breathing |

| Ginger | Gingerol | Warming, zesty | Cooking, sweetness |

This distinction matters in recipe design. While chili heat builds and persists, wasabi’s punch peaks quickly and fades—making it ideal for sushi accompaniments. Piperine from black pepper enhances other flavors without overwhelming, functioning more as a seasoning than a dominant note.

Practical Tips & FAQs

How do I build my spice tolerance?

Regular exposure increases tolerance. Start with milder chilies like poblanos or ancho, then gradually introduce jalapeños and serranos. Over weeks, your pain receptors adapt, allowing you to enjoy hotter dishes without discomfort.

Can I reduce the heat of a chili before using it?

Yes. Remove all seeds and white ribs—the primary reservoirs of capsaicin. Soaking sliced chilies in milk or a saltwater brine for 10–15 minutes can also draw out some capsaicin.

What’s the safest way to handle extremely hot chilies?

Wear nitrile gloves, work in a ventilated area, and avoid touching your face. Clean cutting boards and knives immediately with soapy water. Never use bare hands to adjust glasses or scratch an itch after handling ghost peppers or reapers.

Does cooking affect chili heat?

Yes. Prolonged cooking can mellow heat slightly, especially in liquid-based dishes where capsaicin disperses. However, roasting or charring can intensify perceived heat by concentrating flavors. Frying chilies in oil rapidly releases capsaicin, spreading heat throughout the dish.

Are there non-spicy alternatives for flavor?

Absolute. Use smoked paprika for depth without burn, or blend bell peppers with a touch of cayenne to simulate color and hint of warmth. For a warming sensation without fire, try white pepper or a dash of ground ginger.

How should I store dried chilies and powders?

Keep in airtight containers away from light, heat, and moisture. A cool, dark pantry is ideal. Label with purchase date—most retain potency for 12 months, though flavor diminishes thereafter. Freeze whole dried chilies for extended storage (up to 2 years).

Can I substitute one chili for another?

Yes, but match both heat level and flavor profile. Example: Replace pasilla with mulato for similar fruitiness and medium heat. Avoid substituting habanero for poblano—they differ by over 100x in SHU. When substituting, start with 1/4 the amount and adjust carefully.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Understanding spice heat levels is fundamental to confident, creative cooking. Heat is not merely a test of endurance—it’s a nuanced flavor dimension that, when managed correctly, elevates dishes from flat to unforgettable. The Scoville scale provides a reliable framework for comparing chilies, but real-world application depends on form, preparation, and pairing.

Remember that capsaicin is fat-soluble and concentrated in specific parts of the pepper. Control heat by managing seed inclusion, form selection, and timing of addition. Balance intense chilies with cooling agents like dairy, sweetness, or starch. And respect the power of ultra-hot varieties—handle them with the caution they demand.

Whether you're crafting a gentle ancho-infused mole or experimenting with a Carolina Reaper hot sauce, precision and awareness ensure success. Mastering heat means mastering control. With this knowledge, you’re equipped to navigate the spectrum of spice—from mild warmth to volcanic intensity—with skill and confidence.

Challenge: Try making a three-tiered hot sauce using a mild (poblano), medium (jalapeño), and hot (habanero) chili. Blend each with lime, garlic, and a touch of honey. Taste and compare how heat interacts with supporting flavors. This exercise sharpens your palate and deepens your understanding of balance.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?