Hemophilia is a rare but serious bleeding disorder that impairs the body’s ability to form blood clots. While it can affect anyone, it overwhelmingly appears in males. This gender disparity isn’t random—it’s rooted in genetics and biology. Understanding why hemophilia is more common in males requires exploring how genes are inherited, particularly those located on the sex chromosomes. This article breaks down the science behind hemophilia’s male prevalence, explains carrier dynamics in females, and offers practical insights for families navigating genetic risks.

The Genetic Basis of Hemophilia

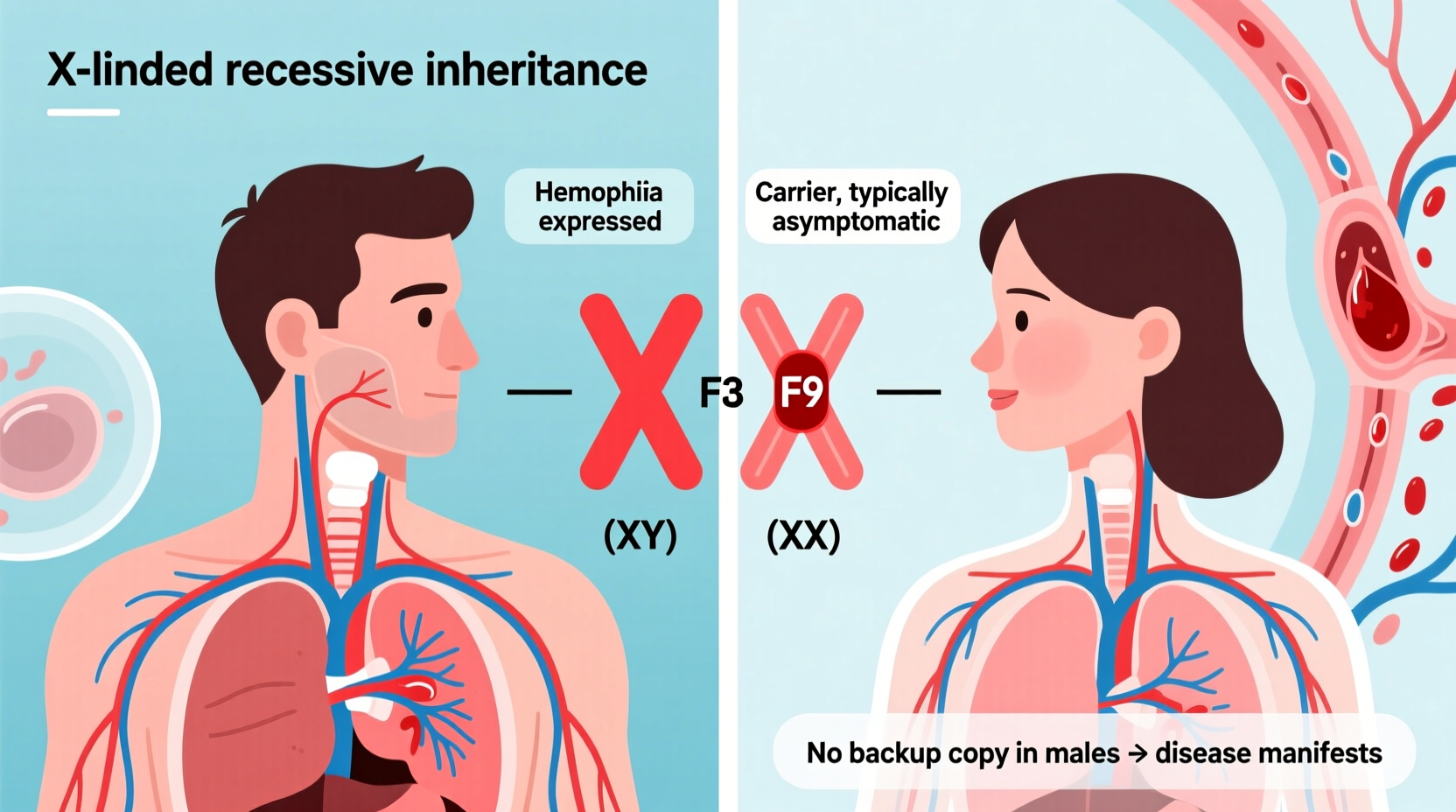

Hemophilia is primarily caused by mutations in genes responsible for producing clotting factors—proteins essential for stopping bleeding. The most common types, Hemophilia A and B, result from deficiencies in Factor VIII and Factor IX, respectively. These genes are located on the X chromosome, one of the two sex chromosomes humans inherit (the other being the Y chromosome).

Because males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY), they only have a single copy of the genes on the X chromosome. If that X carries a defective clotting factor gene, there is no backup copy to compensate. In contrast, females have two X chromosomes (XX). Even if one X has the mutation, the other healthy X can often produce enough clotting factor to prevent severe symptoms.

This fundamental difference in chromosomal makeup explains why males are at much higher risk of expressing hemophilia when they inherit the faulty gene.

How Hemophilia Is Inherited

The inheritance pattern of hemophilia follows what is known as X-linked recessive transmission. This means the gene mutation resides on the X chromosome, and the trait is “recessive”—requiring both copies to be defective for full expression in females.

Here’s how it typically unfolds:

- A male with hemophilia passes his Y chromosome to his sons (who will not inherit the condition) and his affected X chromosome to his daughters (who become carriers).

- A female carrier has a 50% chance of passing the mutated X chromosome to each child. Sons who inherit it will have hemophilia; daughters who inherit it will be carriers.

- If a father does not have hemophilia and the mother is not a carrier, the risk to children is extremely low.

It’s important to note that about one-third of hemophilia cases occur due to spontaneous mutations—meaning there is no family history. These arise during conception or early fetal development and can still follow the same X-linked pattern.

Real Example: The Royal Family Case

One of the most famous historical examples of X-linked inheritance is seen in European royal families. Queen Victoria of England is believed to have been a carrier of hemophilia B. Though she did not show symptoms, she passed the gene to several of her children. Her son Leopold had hemophilia and suffered frequent bleeding episodes, dying at age 30 after a minor fall led to fatal brain hemorrhage. Two of her daughters were carriers, spreading the gene to royal houses in Spain, Germany, and Russia. Her grandson, Alexei, son of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, famously endured severe hemophilia, influencing political decisions and contributing to the instability of the Russian monarchy.

This lineage illustrates how a single carrier female can transmit a recessive X-linked disorder across generations, predominantly affecting male descendants.

“Hemophilia provides a textbook example of X-linked recessive inheritance. It's crucial for clinicians and families to understand this pattern to manage risk and provide early intervention.” — Dr. Linda Rodriguez, Medical Geneticist, Mayo Clinic

Why Females Rarely Develop Severe Hemophilia

Females are not immune to hemophilia, but symptomatic cases are uncommon. For a female to have full-blown hemophilia, she must inherit two defective copies—one from each parent. This scenario is rare because it requires a man with hemophilia to have children with a woman who is either a carrier or also has the condition.

However, some female carriers do experience mild symptoms such as easy bruising, heavy menstrual bleeding, or prolonged bleeding after surgery or childbirth. These individuals are sometimes referred to as having \"symptomatic carriers\" or mild hemophilia. Recent medical awareness has led to better diagnosis and treatment for these women, who may previously have been overlooked.

In rare cases, skewed X-chromosome inactivation (also called lyonization) can lead to more pronounced symptoms in females. Normally, one X chromosome is randomly inactivated in each cell. If the healthy X is inactivated in a majority of cells, the mutated X becomes dominant, leading to lower clotting factor levels.

Diagnosis and Management Across Genders

Early diagnosis is critical for managing hemophilia effectively. Newborn screening is not routine, so boys with a family history should be tested shortly after birth. Diagnosis involves blood tests measuring clotting factor activity levels:

| Severity Level | Factor Activity | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 5–40% of normal | Bleeding after surgery or trauma |

| Moderate | 1–5% of normal | Occasional spontaneous bleeding |

| Severe | Less than 1% | Frequent spontaneous joint and muscle bleeds |

Treatment primarily involves replacing the missing clotting factor through intravenous infusions. Prophylactic (preventive) treatment is standard for severe cases, especially in children, to protect joints and maintain quality of life. Advances like extended-half-life products and non-factor therapies (e.g., emicizumab) have significantly improved outcomes.

Females with symptoms should also be evaluated. Many are misdiagnosed with gynecological disorders before their clotting issue is identified. Testing clotting factors in women with abnormal bleeding is increasingly recognized as best practice.

Step-by-Step Guide: What to Do If Hemophilia Runs in Your Family

- Document your family history: Note any relatives with bleeding disorders, excessive bruising, or prolonged bleeding after procedures.

- Consult a genetic counselor: They can map out inheritance patterns and estimate risks for future children.

- Get tested if you’re a potential carrier: Women with a family history should undergo clotting factor assays and genetic testing.

- Discuss prenatal options: Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis can detect hemophilia in a male fetus.

- Plan for delivery: If a male baby is at risk, delivery should occur in a hospital with hematology support to avoid traumatic birth injuries.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a girl have hemophilia?

Yes, though it's rare. A girl must inherit two defective X chromosomes—one from each parent. More commonly, girls are carriers and may have mild bleeding symptoms.

Is hemophilia curable?

There is no widespread cure yet, but gene therapy is showing promise. Clinical trials have enabled some patients to produce functional clotting factors after a single treatment, drastically reducing bleeding episodes.

Does hemophilia skip generations?

It may appear to skip generations because female carriers often don’t show symptoms. The condition can re-emerge in a grandson if the mother is a carrier, creating the illusion that it skipped a generation.

Conclusion: Awareness Saves Lives

The reason hemophilia is more common in males lies in our biology—specifically, the X-linked recessive inheritance pattern. Males lack a genetic backup when the clotting gene on their single X chromosome is defective. Females, with two X chromosomes, are usually protected unless both copies are affected or inactivation is skewed.

Understanding this mechanism empowers families to take preventive steps, seek early diagnosis, and access life-changing treatments. As research advances, gene therapy may one day offer long-term solutions. Until then, education, genetic counseling, and proactive care remain vital tools in managing this condition.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?