A high BUN (blood urea nitrogen) to creatinine ratio is a common finding in routine blood tests and can signal underlying health issues, particularly related to kidney function, hydration, or gastrointestinal conditions. While both BUN and creatinine are markers of kidney health, their ratio provides additional context that isolated values may not. Understanding what an elevated ratio indicates—and what factors influence it—can help patients and healthcare providers make informed decisions about diagnosis and treatment.

Understanding BUN and Creatinine

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine are waste products filtered by the kidneys. BUN results from protein metabolism in the liver, while creatinine is a byproduct of muscle breakdown. Healthy kidneys efficiently remove these substances from the bloodstream, maintaining stable levels.

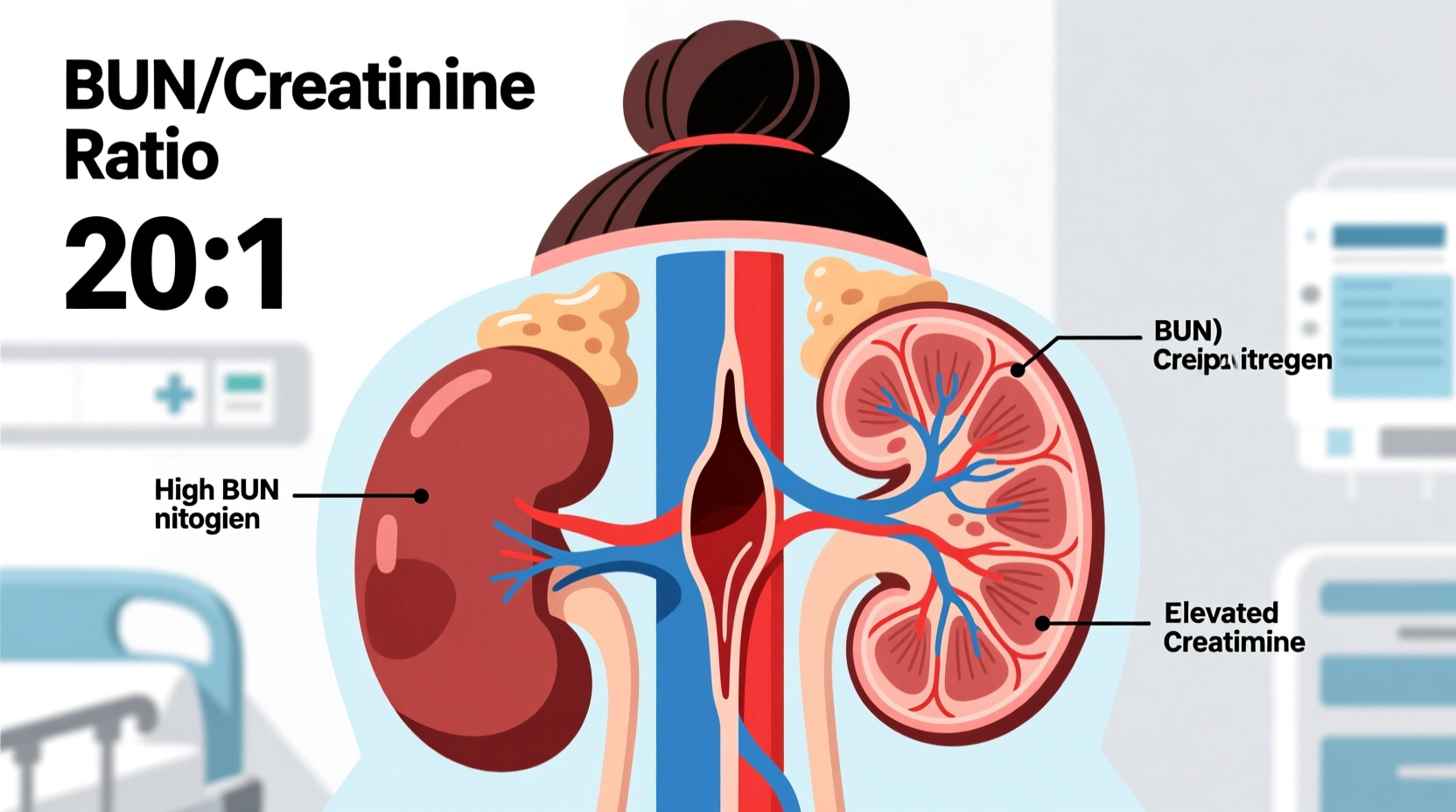

The BUN-to-creatinine ratio is calculated using the formula:

In adults, a normal ratio typically ranges between 10:1 and 20:1. A value above 20:1 is generally considered high and warrants further investigation. However, interpretation must consider clinical context—including hydration, diet, medications, and overall health.

Common Causes of a High Ratio

An elevated BUN-to-creatinine ratio often points to prerenal causes—conditions affecting blood flow to the kidneys rather than direct kidney damage. Key contributors include:

- Dehydration: Reduced fluid volume decreases kidney perfusion, causing BUN to rise disproportionately compared to creatinine.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding: Blood in the digestive tract increases protein breakdown, elevating BUN levels.

- Heart failure: Poor cardiac output reduces renal blood flow, mimicking dehydration effects.

- High-protein diets or steroid use: Increased protein intake or catabolic states boost urea production.

- Corticosteroid therapy: These medications increase protein breakdown and BUN without affecting creatinine.

Less commonly, a high ratio may occur due to urinary tract obstruction early in the disease process, though this often progresses to equal elevation of both markers as kidney function declines.

When Kidney Disease Is Not the Cause

It’s crucial to distinguish between prerenal azotemia (reduced kidney perfusion) and intrinsic kidney disease. In prerenal conditions, the kidneys are structurally intact but underperfused. The high BUN-to-creatinine ratio reflects selective retention of urea due to increased reabsorption in the proximal tubules when blood flow is low.

For example, a patient who has been vomiting for two days, avoiding fluids, and taking NSAIDs may present with a BUN of 32 mg/dL and creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL—yielding a ratio of 29:1. Despite elevated BUN, the near-normal creatinine suggests preserved kidney function, with dehydration as the likely culprit.

“An elevated BUN-to-creatinine ratio above 20:1 should prompt evaluation for volume depletion or GI bleeding before diagnosing chronic kidney disease.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Nephrologist, Mayo Clinic

Mini Case Study: Dehydration in an Elderly Patient

Mrs. Thompson, a 78-year-old woman, visited her primary care clinic complaining of dizziness and fatigue. Her lab results showed:

| Test | Result | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| BUN | 36 mg/dL | 7–20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.0 mg/dL | 0.6–1.2 mg/dL |

| BUN/Creatinine Ratio | 36:1 | 10–20:1 |

Her physical exam revealed dry mucous membranes and low blood pressure. She admitted to reduced fluid intake due to fear of frequent urination at night. With oral rehydration and education on balanced fluid consumption, her follow-up labs one week later showed BUN of 18 mg/dL and a normalized ratio of 15:1—confirming prerenal azotemia due to dehydration.

Differentiating High Ratio from True Kidney Injury

True acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) usually presents with proportional increases in both BUN and creatinine, resulting in a normal or only mildly elevated ratio. When both markers rise together, it indicates impaired glomerular filtration across the board.

To differentiate, clinicians assess:

- Urinalysis (looking for casts, protein, or sediment suggestive of intrinsic disease)

- Urine sodium and fractional excretion of urea (FeUrea)

- Response to fluid challenge

- Medical history (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, medication use)

A FeUrea below 35% supports a prerenal cause, whereas values above 50% suggest intrinsic renal damage.

Step-by-Step: Evaluating a High BUN Creatinine Ratio

- Review lab values: Confirm both BUN and creatinine; calculate the ratio.

- Assess hydration status: Check for signs of dehydration (dry skin, low BP, elevated heart rate).

- Evaluate dietary intake: Ask about recent high-protein meals, supplements, or steroid use.

- Screen for GI bleeding: Look for melena, hematemesis, or positive fecal occult blood.

- Check medications: Identify nephrotoxins (NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors, diuretics).

- Order additional tests: Urinalysis, electrolytes, albumin, CBC, and possibly renal ultrasound.

- Monitor trends: Repeat labs after rehydration to see if the ratio normalizes.

Potential Misinterpretations and Pitfalls

Several factors can distort the BUN-to-creatinine ratio, leading to misdiagnosis if not carefully evaluated:

| Situation | Effect on Ratio | Why It Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced liver disease | Low ratio (<10:1) | Reduced urea production due to impaired liver function |

| Rhabdomyolysis | Low ratio | Massive creatinine release from muscle breakdown |

| Malnutrition or low protein diet | Low BUN, potentially low ratio | Decreased substrate for urea synthesis |

| Recent dialysis | Variable | BUN drops faster than creatinine post-treatment |

This highlights why a comprehensive patient history is essential. For instance, a bodybuilder with rhabdomyolysis after intense training may have a creatinine of 3.0 mg/dL and BUN of 18 mg/dL—giving a ratio of 6:1. This low ratio doesn’t indicate good kidney function but rather massive creatinine spillage.

FAQ

Can a high BUN creatinine ratio be temporary?

Yes. Dehydration, short-term high-protein intake, or minor GI bleeding can cause a transient rise in the ratio. Once the underlying issue resolves—such as rehydration—the ratio often returns to normal within days.

Should I worry if my ratio is 25:1 but creatinine is normal?

Not necessarily. A mildly elevated ratio with normal creatinine is commonly due to dehydration or dietary factors. However, persistent elevation or accompanying symptoms (like fatigue, swelling, or dark urine) should prompt further evaluation by a healthcare provider.

Does a high ratio always mean kidney problems?

No. In fact, a high ratio often indicates that the kidneys are responding appropriately to stress (like low blood flow), rather than being damaged. True kidney dysfunction usually shows with rising creatinine and a stable or lower ratio.

Action Plan: What to Do If Your Ratio Is High

“Don’t panic over a single lab value. Focus on patterns and context.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Internal Medicine Specialist

If you’ve received lab results showing a high BUN-to-creatinine ratio, consider the following checklist:

✅ High BUN Creatinine Ratio: Action Checklist

- ☑️ Review your fluid intake over the past 24–48 hours

- ☑️ Assess for symptoms of dehydration (thirst, dizziness, dark urine)

- ☑️ Consider recent dietary changes (high meat intake, protein shakes)

- ☑️ Note any medications (especially diuretics, NSAIDs, steroids)

- ☑️ Look for signs of GI bleeding (black stools, vomiting blood)

- ☑️ Avoid strenuous exercise until evaluated

- ☑️ Schedule a follow-up test with your doctor, ideally after proper hydration

Conclusion

A high BUN-to-creatinine ratio is a valuable clue—not a definitive diagnosis. It often reflects temporary imbalances like dehydration or increased protein catabolism rather than irreversible kidney damage. By understanding the physiology behind these markers and considering the full clinical picture, patients and providers can avoid unnecessary concern and focus on actionable steps. Hydration, diet awareness, and timely medical follow-up remain key.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?