Fermentation is not just a method of preservation—it's a biochemical alchemy that turns simple cucumbers into complex, tangy, probiotic-rich pickles. While vinegar-based quick pickles dominate supermarket shelves, traditional fermented pickles undergo a slow, microbial transformation that enhances flavor, texture, and nutritional value. Understanding this process empowers home cooks to create deeply flavored, living foods while connecting with culinary traditions spanning millennia. The distinction between fermented and acidified pickles goes beyond taste; it involves microbiology, food safety, and sensory science. This article explores the science and craft behind fermented pickles, detailing how salt, time, and bacteria work in harmony to transform crisp cucumbers into sour, savory delights.

Definition & Overview

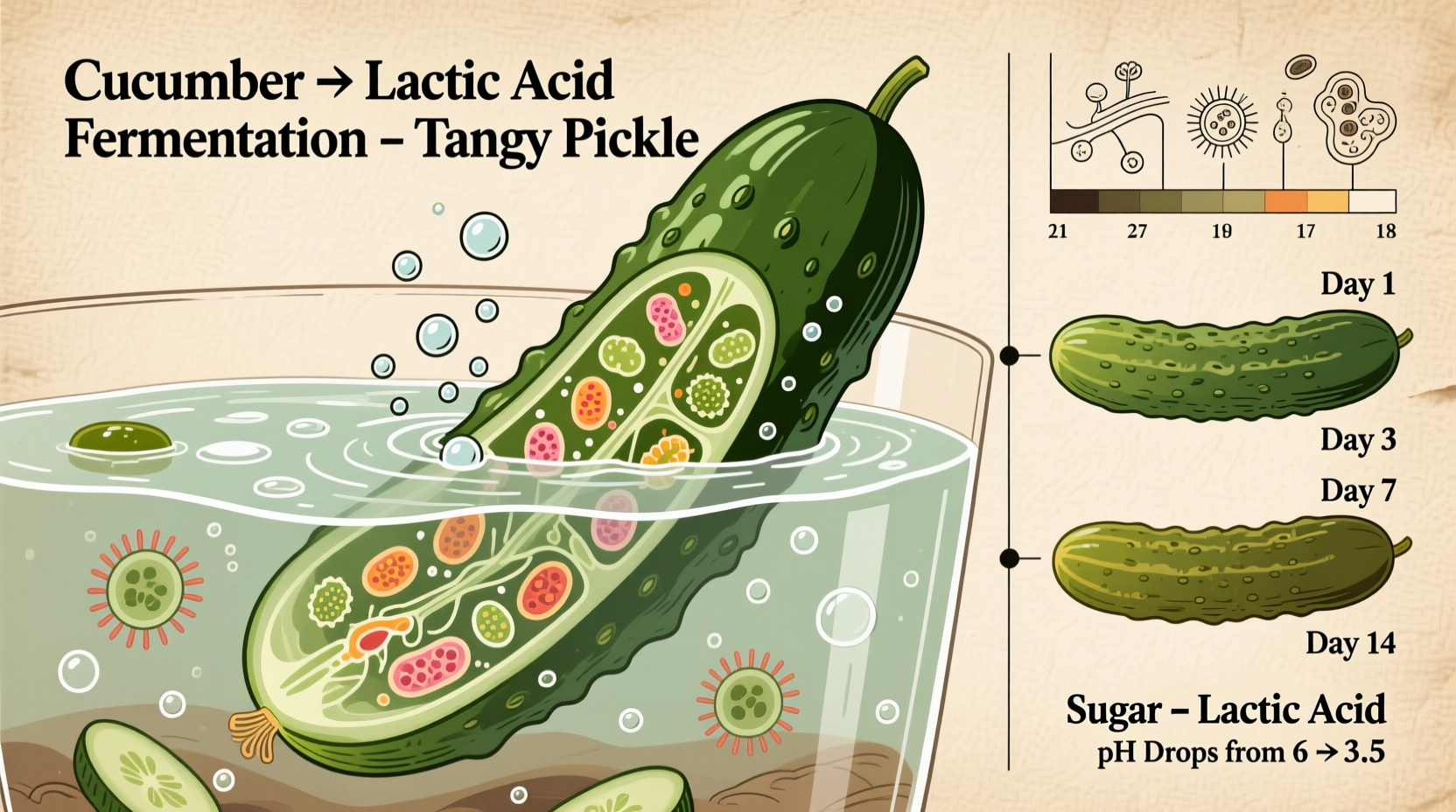

Fermented pickles are cucumbers preserved through lactic acid fermentation—a natural process driven by beneficial bacteria, primarily Lactobacillus species. Unlike vinegar-brined pickles, which rely on acetic acid for preservation and tartness, fermented pickles generate their own acidity as microbes convert sugars into lactic acid. This self-preserving reaction occurs in an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment created by submerging cucumbers in a saltwater brine. Originating long before refrigeration, this technique was historically used across Eastern Europe, Korea, India, and the Middle East to preserve seasonal produce. Today, fermented pickles—such as Polish-style half-sour or full-sour cucumbers, German sauerkraut (from cabbage), and Korean kimchi—are celebrated not only for their bold flavors but also for their contribution to gut health.

The term \"pickle\" broadly refers to any vegetable preserved in an acidic medium, but true fermented pickles develop acidity biologically rather than through added vinegar. The starting ingredients are minimal: fresh cucumbers (preferably unwaxed and blemish-free), non-iodized salt, water, and often aromatic additions like garlic, dill, mustard seed, or grape leaves. Over days or weeks, ambient microbes initiate fermentation, gradually lowering the pH and creating an inhospitable environment for pathogens while enhancing palatability.

Key Characteristics of Fermented Pickles

Fermentation fundamentally alters the chemical and sensory profile of cucumbers. These changes define the identity of traditionally made pickles:

- Flavor: Develops from mild and vegetal to tangy, sour, and umami-rich. Complexity increases over time with notes of earthiness, spice, and subtle funk.

- Aroma: Bright and vinegary at first, evolving into deeper, fermented scents reminiscent of yogurt, sourdough, or aged cheese.

- Texture: Crisp initially due to pectin integrity; prolonged fermentation can soften texture, though tannin-rich leaves (like oak or grape) help maintain crunch.

- Color: Fresh green hue darkens slightly during fermentation but remains vibrant if processed correctly.

- Acidity Level: Ranges from mildly tart (pH ~4.0) to sharply sour (pH ~3.2–3.5), depending on duration and temperature.

- Culinary Function: Acts as a palate cleanser, condiment, or ingredient adding brightness and depth to sandwiches, charcuterie boards, grain bowls, and stews.

- Shelf Life: Properly fermented and stored (refrigerated, sealed), they last 4–12 months, continuing to mature slowly.

- Nutritional Profile: Contains live probiotics, B vitamins, and increased bioavailability of certain minerals due to microbial activity.

| Attribute | Fermented Pickles | Vinegar-Brined Pickles |

|---|---|---|

| Acid Source | Lactic acid (produced by bacteria) | Acetic acid (added vinegar) |

| Microbial Activity | Live cultures present (probiotic) | No active microbes (sterile after canning) |

| Taste Development | Evolves over time | Fixed upon bottling |

| Preparation Time | Days to weeks | Hours (quick-pickled) |

| Storage Stability | Refrigeration required for long-term storage | Room temperature stable (if canned) |

| Nutritional Benefit | Probiotics, enzyme activity | Low calorie, no live cultures |

Practical Usage: How Fermentation Works in Real Cooking

To make fermented pickles at home, one must understand the stages of fermentation and how environmental factors influence outcomes. The process begins when sliced or whole cucumbers are packed into a jar with spices and submerged in a 3–5% saltwater brine (30–50 grams of salt per liter of water). The salt inhibits spoilage organisms while allowing halotolerant lactic acid bacteria (LAB) to thrive.

The fermentation progresses through three general phases:

- Initial Phase (Days 1–2): Aerobic microbes consume oxygen; Enterobacteria may briefly dominate before being outcompeted.

- Active Fermentation (Days 3–7): LAB such as Leuconostoc mesenteroides begin producing carbon dioxide and lactic acid, lowering pH and creating sourness. Bubbles may appear—this is normal and indicates microbial activity.

- Maturation Phase (Week 2+): More acid-tolerant strains like Lactobacillus plantarum take over, further increasing acidity and stabilizing the product.

Temperature plays a critical role: ideal fermentation occurs between 68°F and 72°F (20°C–22°C). Warmer temperatures accelerate fermentation but risk softening textures and encouraging undesirable microbes; cooler environments slow the process but yield cleaner flavors.

Tip: To ensure crispness, add a source of tannins—such as a small grape leaf, black tea bag, or oak leaf—to your jar. Tannins inhibit pectinolytic enzymes that break down cell walls and cause mushiness.

Once fermented to taste (typically 1–3 weeks), jars should be moved to cold storage to halt microbial activity. Taste-testing every few days allows precise control over sourness. These pickles enhance dishes far beyond the sandwich realm:

- Add chopped fermented dill pickles to potato salad for a brighter, more complex tang than vinegar alone.

- Puree into a remoulade sauce with mayonnaise, capers, and lemon zest for seafood dipping.

- Include whole spears alongside grilled meats or roasted vegetables to cut richness.

- Use pickle brine in place of vinegar in dressings or marinades for added depth.

- Incorporate into Bloody Mary mix—the natural umami and acidity elevate the cocktail.

Professional kitchens increasingly use house-fermented pickles to differentiate menus. Chefs layer them in composed dishes—not just for acidity, but for textural contrast and microbial terroir. Some restaurants even age fermented pickles for months, developing deep, funky profiles akin to fine cheeses.

Variants & Types of Fermented Pickles

While cucumber-based ferments are most common in Western contexts, global variations demonstrate the versatility of lactic acid fermentation. Each type reflects regional ingredients, climate, and tradition:

1. Half-Sour Pickles (Poland/Eastern Europe)

Mildly fermented for 3–7 days, these pickles retain a fresh cucumber flavor with a slight tang. They are typically refrigerated early to stop full souring, preserving crispness and green color. Best consumed within weeks.

2. Full-Sour Fermented Pickles

Allowed to ferment completely (2–4 weeks), these develop intense sourness and softer rinds. Often seasoned with garlic, dill, and peppercorns. Shelf-stable when refrigerated and commonly found in Jewish delis.

3. Kimchi (Korea)

Though made primarily with napa cabbage, many kimchi varieties include radish or cucumber. Seasoned with gochugaru (Korean chili flakes), fish sauce, ginger, and scallions, it undergoes rapid fermentation at room temperature before refrigeration. Offers both heat and sourness with effervescence.

4. Achar (South Asia)

Indian and Pakistani fermented vegetable mixes often include mango, lime, or carrots preserved in oil and salt. Fermentation may be partial or complete, yielding spicy, pungent condiments served in tiny portions with meals.

5. Lacto-Fermented Bread-and-Butter Style

A modern twist combining traditional fermentation with sweet-sour flavor profiles. Onions, peppers, and cucumbers are brined with turmeric, mustard seed, and a touch of sugar, then fermented. The result mimics classic bread-and-butter pickles but with live cultures and greater complexity.

| Type | Best For | Fermentation Duration | Flavor Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Half-Sour | Delicate dishes, appetizers | 3–7 days | Fresh, lightly tangy |

| Full-Sour | Hearty sandwiches, pastrami accompaniments | 2–4 weeks | Sharp, savory, garlicky |

| Kimchi | Stir-fries, rice bowls, jjigae (stews) | 1–7 days (then refrigerate) | Spicy, umami, fermented funk |

| Achar | Accompaniment to curries and flatbreads | 2 weeks–6 months | Salty, oily, pungent |

| Sweet-Lacto Mix | Cheese boards, burgers | 5–10 days | Balanced sweet-sour, aromatic |

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Fermented pickles are often confused with other preserved vegetables, but key differences exist:

- Vinegar-Pickled Cucumbers: Instantly acidic due to vinegar immersion. No microbial transformation occurs. Texture and flavor remain static. Lacks probiotics.

- Refrigerator Pickles: Typically vinegar-based and stored cold. Made quickly (within hours), they offer convenience but not fermentation benefits.

- Canned Fermented Pickles: Rare. Most commercial “fermented” pickles are pasteurized, killing live cultures. True raw fermented pickles are labeled “unpasteurized” or “contains live cultures.”

- Sauerkraut/Japanese Tsukemono: Same principle (lactic acid fermentation) applied to different vegetables. Sauerkraut uses shredded cabbage; tsukemono may involve rice bran (nukazuke) or salt-only brines.

\"The beauty of fermentation lies in its unpredictability. Two jars started on the same day can develop distinct personalities—one brighter, one deeper—based on microbial diversity and micro-environment. That’s not inconsistency; that’s terroir.\" — Sandor Katz, author of *The Art of Fermentation*

Practical Tips & FAQs

What kind of cucumbers should I use?

Opt for pickling cucumbers—small, firm, thin-skinned varieties like Kirby or Amsterdam Gherkin. Avoid waxed cucumbers, as wax prevents brine penetration and promotes spoilage. Harvested fresh and used within 24 hours, they yield the crispest results.

Can I use table salt?

No. Table salt contains iodine and anti-caking agents that can inhibit fermentation and darken pickles. Use non-iodized salts such as sea salt, kosher salt, or pickling salt.

Why is my brine cloudy?

Cloudiness is normal during active fermentation and results from bacterial growth and suspended solids. As long as there’s no mold, foul odor, or sliminess, cloudiness indicates healthy fermentation.

How do I prevent mold?

Ensure cucumbers stay fully submerged under brine using fermentation weights or a small zip-top bag filled with brine. Exposure to air invites yeast and mold. Skim any surface growth early, but discard if extensive or colored.

Can I speed up fermentation?

Increasing temperature accelerates fermentation but risks off-flavors and texture loss. Never add vinegar to “speed up” the process—that halts lactic acid bacteria and defeats the purpose of fermentation.

Are fermented pickles safe?

Yes, when prepared correctly. The drop in pH (<4.6) creates an environment hostile to dangerous pathogens like Clostridium botulinum. Always follow tested guidelines, use clean equipment, and trust your senses: discard if foul-smelling, slimy, or moldy.

Do I need special equipment?

Not necessarily. Clean glass jars with tight lids work well. For consistent results, consider fermentation-specific gear: airlock lids (to release CO₂ while blocking oxygen), ceramic crocks, or Harsch-style crocks with water seals.

Can I reuse brine?

Yes—fermentation brine, known as \"pickle juice,\" can inoculate new batches, marinate proteins, or be sipped as a mineral-rich electrolyte drink (popular among athletes for cramp relief).

Checklist for Successful Fermentation:

- Use fresh, unwaxed cucumbers

- Measure salt precisely (3–5% brine)

- Submerge vegetables completely

- Ferment at 68–72°F (20–22°C)

- Taste regularly after Day 5

- Refrigerate once desired sourness is reached

- Label jars with start date

Summary & Key Takeaways

Fermentation transforms pickles through a precise interplay of salt, bacteria, and time. It converts simple cucumbers into dynamic, living foods rich in flavor, texture, and health-promoting microbes. Unlike vinegar-based counterparts, fermented pickles evolve, offering ever-changing sensory experiences. Their production requires minimal ingredients but rewards attention to detail—particularly in maintaining anaerobic conditions, using proper salt levels, and monitoring temperature.

The process connects modern eaters with ancient food wisdom, turning preservation into an art form. Whether you're crafting half-sours for next week’s Reuben sandwich or experimenting with global styles like kimchi or achar, understanding fermentation unlocks deeper culinary possibilities. Beyond taste, these pickles contribute to digestive wellness and represent a sustainable approach to food storage without reliance on artificial preservatives.

Embracing fermented pickles means embracing variability, patience, and microbial collaboration. With each batch, you’re not just making pickles—you’re cultivating a miniature ecosystem where science and tradition converge on the dinner plate.

Start small: pack a quart jar with cucumbers, garlic, dill, and a 4% salt brine. Taste weekly. Observe the transformation. In doing so, you join a lineage of fermenters stretching back thousands of years—one sour, crunchy bite at a time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?