Garlic (Allium sativum) is one of the most widely used culinary ingredients in global cuisines, prized for its pungent aroma, complex flavor, and medicinal properties. Yet few home cooks or even gardeners fully understand how this humble bulb comes into being. The transformation from a single clove planted in cool soil to a mature, multi-cloved bulb is a carefully orchestrated biological process influenced by genetics, seasonality, temperature, and agricultural practice. Understanding how garlic forms and develops bulbs is essential not only for successful cultivation but also for appreciating the ingredient’s seasonal availability, flavor evolution, and optimal use in cooking. This article explores the science behind garlic bulb formation, detailing each stage of development, the environmental triggers involved, and practical implications for growers and food enthusiasts alike.

Definition & Overview: What Is Garlic and How Does It Reproduce?

Garlic is a member of the Alliaceae family, closely related to onions, leeks, and shallots. Unlike many vegetables that reproduce via seeds, commercial garlic is typically propagated asexually—each clove from a mature bulb can grow into a new plant. This method preserves genetic consistency and ensures reliable crop performance. While garlic can produce flowers and true seeds under certain conditions, especially in hardneck varieties, most cultivated garlic never reaches sexual maturity. Instead, energy is directed toward vegetative reproduction: forming a new underground bulb composed of multiple cloves.

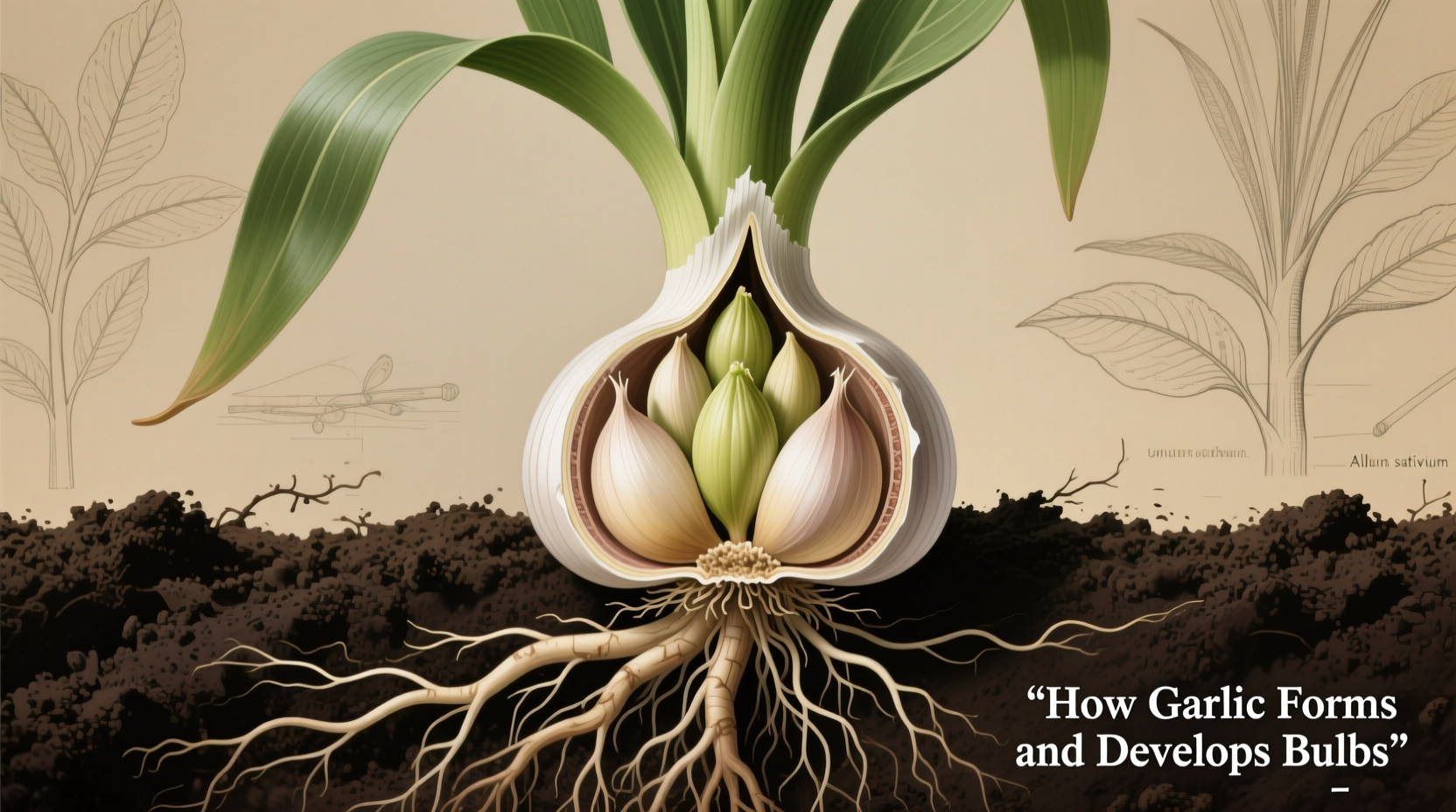

The bulb itself is a modified stem surrounded by fleshy leaf bases—the cloves—encased in protective dry sheaths. These structures store nutrients and allow the plant to survive dormancy, making garlic well-adapted to seasonal climates. The entire life cycle of a garlic plant spans approximately 8 to 10 months, depending on climate and variety, with bulb formation occurring during specific physiological phases triggered primarily by photoperiod and temperature changes.

Key Characteristics of Garlic Bulb Development

- Vegetative Propagation: Grown from individual cloves rather than seeds.

- Bulbing Trigger: Initiated by increasing day length (photoperiod) and rising temperatures.

- Growth Duration: Typically 240–300 days from planting to harvest.

- Clove Formation: A single planted clove divides into multiple genetically identical cloves within the developing bulb.

- Differentiation Timing: Clove initiation begins several weeks before visible bulbing.

- Environmental Sensitivity: Requires vernalization (exposure to cold) for proper development.

- Maturity Indicator: Top leaves begin to yellow and die back when bulbs are nearing harvest readiness.

The Biological Stages of Garlic Bulb Formation

Garlic development occurs in distinct, interdependent stages. Each phase sets the foundation for the next, and disruption at any point can impair bulb size, quality, or yield.

Stage 1: Planting and Root Development (Autumn – Early Winter)

Garlic is usually planted in the fall, 4–6 weeks before the ground freezes. This timing allows the clove to establish a robust root system without initiating significant top growth. Cooler soil temperatures (below 50°F / 10°C) promote root elongation while suppressing leaf emergence. This period is critical for vernalization—the exposure to prolonged cold that signals the plant to initiate reproductive development later in the season.

During this phase, metabolic activity focuses on absorbing water and nutrients. Roots anchor the plant and prepare it to draw resources rapidly once spring arrives. No visible signs of bulbing occur yet, but internal hormonal shifts are beginning to set the stage for future clove differentiation.

Stage 2: Spring Regrowth and Leaf Initiation (Late Winter – Early Spring)

As temperatures rise above 40°F (4°C), garlic resumes active growth. Green shoots emerge from the soil, and new leaves begin to unfurl sequentially from the central growing point. Each leaf corresponds directly to a future wrapper layer around the bulb. The number of leaves formed during this stage largely determines the potential size of the mature bulb—more leaves mean more layers and larger cloves.

At this stage, the plant relies heavily on photosynthesis. Healthy, dark green foliage indicates strong energy production, which will later be redirected to bulb formation. Growers must ensure adequate nitrogen supply early in this phase to support vigorous leaf growth, though excess nitrogen later can delay bulbing or encourage soft-neck disease.

Stage 3: Bulb Initiation (Late Spring)

Bulb initiation marks the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. Despite being asexual, garlic undergoes a physiological shift akin to flowering induction in seed-producing plants. This shift is primarily controlled by two environmental cues:

- Photoperiod: Garlic responds to increasing day length. Once daylight exceeds 12–14 hours per day (depending on variety), hormonal signals trigger meristem transformation.

- Soil Temperature: Sustained soil temperatures above 60°F (15.5°C) accelerate the process.

Internally, the apical meristem—which previously produced leaves—ceases leaf formation and begins dividing laterally. These lateral buds become individual cloves. Simultaneously, the base plate (the flat bottom of the bulb) thickens and starts storing carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis.

TIP: Select garlic varieties adapted to your region’s day length. Southern (short-day) types initiate bulbs earlier under shorter photoperiods, while northern (long-day) varieties require longer days. Using the wrong type results in small, poorly developed bulbs.

Stage 4: Clove Expansion and Bulb Maturation (Early to Mid-Summer)

Once initiated, the bulb enters a rapid growth phase. Energy from the leaves is translocated downward into the developing cloves. The outer scales harden, forming protective layers, while inner tissues accumulate sugars, amino acids, and sulfur compounds responsible for garlic’s characteristic pungency.

This stage lasts 4–6 weeks and is highly sensitive to water and nutrient availability. Consistent moisture is crucial—dry spells cause stunted bulbs, while overwatering near harvest promotes rot. As the plant matures, older leaves naturally senesce, turning brown from the tips downward. When about half of the leaves have died back, the bulb has reached physiological maturity and should be harvested promptly to avoid splitting or deterioration.

Stage 5: Harvest and Curing

Harvesting too early yields underdeveloped bulbs with thin skins prone to spoilage. Waiting too long risks clove separation and reduced shelf life. The ideal time is when 5–6 lower leaves have yellowed, but 5–6 upper leaves remain green.

After digging, garlic must be cured—a drying process lasting 2–4 weeks in a warm, shaded, well-ventilated area. Curing halts enzymatic activity, concentrates flavor, toughens outer wrappers, and extends storage life. Properly cured bulbs can last 6–12 months depending on type.

Variants & Types: How Bulb Formation Differs Across Garlic Classes

Not all garlic behaves the same way during bulb development. Two main subspecies dominate cultivation, each with unique growth patterns and environmental needs:

| Type | Subspecies | Day Length Requirement | Bulb Characteristics | Bulbing Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardneck Garlic | Allium sativum var. ophioscorodon | Long-day (14+ hours) | 4–12 large, evenly sized cloves arranged around a central stalk; stiff flower stalk (scape) | Bulbs form reliably after vernalization; scapes must be removed to maximize bulb size |

| Softneck Garlic | Allium sativum var. sativum | Short- to mid-day (10–13 hours) | 12–20 smaller cloves in layered concentric rings; no central scape | Less dependent on cold; better suited to mild climates; higher yields but smaller individual cloves |

A third category, Creole garlic, often grouped with softnecks but genetically distinct, thrives in warmer regions and produces richly flavored, copper-skinned bulbs with moderate clove counts (6–12). Creoles initiate bulbs earlier and tolerate less chilling than hardnecks.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Garlic is frequently confused with other alliums, both in the garden and in the kitchen. Understanding differences in structure and development clarifies their distinct uses.

| Ingredient | Propagation Method | Bulb Structure | Development Time | Flavor Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garlic | Cloves (asexual) | Multiple cloves in a single bulb | 8–10 months | Pungent, spicy, sulfurous; mellows when cooked |

| Onion | Seeds or sets | Single layered bulb from leaf bases | 3–5 months | Sweet to sharp; high sugar content when mature |

| Shallot | Seeds or offsets | Clusters of small bulbs (like multiplier garlic) | 6–7 months | Mild, garlicky-onion hybrid; delicate sweetness |

| Elephant Garlic | Cloves | Large cloves, fewer per bulb | 9–10 months | Mild, leek-like; not true garlic |

\"Many people think garlic just 'grows' like any other vegetable. But it's actually a finely tuned response to seasonal rhythms. Get the timing wrong—even by a few weeks—and you'll end up with something closer to scallions than storage bulbs.\" — Dr. Elena Torres, Horticultural Scientist, University of California Cooperative Extension

Practical Usage: Implications for Cooking and Storage

The way garlic forms and matures directly affects its culinary qualities. Freshly harvested garlic (often called \"wet\" or \"green\" garlic) has higher moisture content, milder flavor, and softer texture. It’s excellent for roasting, sautéing, or blending into sauces but doesn’t store well.

In contrast, fully cured garlic develops sharper pungency due to increased allicin production—a compound formed when cell walls are damaged (e.g., chopped or crushed). This makes cured garlic ideal for raw applications like dressings, aioli, or garnishes where bold flavor is desired.

Chefs and home cooks should consider the following usage guidelines:

- Fresh Garlic (uncured): Use within 2–3 weeks; treat like a vegetable in stir-fries or soups.

- Cured Garlic: Store in mesh bags or baskets; use for long-cooked dishes, infusions, or raw preparations.

- Roasting Whole Heads: Best done with fully mature bulbs; heat transforms pungency into caramelized sweetness.

- Preserving: Can be frozen, dehydrated, or pickled—but curing remains the most effective preservation method.

PRO TIP: For maximum flavor impact, chop or crush garlic and let it sit for 5–10 minutes before cooking. This allows alliinase enzymes to convert alliin into allicin, enhancing both taste and health benefits.

Storage, Shelf Life, and Substitutions

Proper storage hinges on understanding how garlic was grown and cured:

Q: How long does garlic last?

A: Hardneck varieties last 4–6 months; softnecks can last 9–12 months when stored properly in cool (55–65°F), dry, dark conditions with good airflow. Avoid refrigeration unless pickled, as moisture encourages sprouting or mold.

Q: Why does my garlic sprout or turn green?

A: Sprouting occurs when dormant bulbs are exposed to warmth and humidity. Green centers are safe to eat but indicate aging; they may taste bitter. Remove the germ before using if desired.

Q: Can I substitute minced jarred garlic for fresh?

A: Not ideally. Jarred garlic lacks enzymatic activity and depth of flavor. One teaspoon of jarred equals roughly one small clove, but expect muted results. Freeze fresh minced garlic in oil for a superior alternative.

Q: What if I don’t have time to grow garlic?

A: Look for locally grown, freshly harvested garlic at farmers markets in summer. Alternatively, purchase seed garlic in autumn from reputable suppliers to start your own crop.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Garlic bulb formation is a precise, seasonally driven process rooted in plant physiology and environmental response. From fall planting through vernalization, leaf development, photoperiod-sensitive bulbing, and final maturation, every stage influences the quality and usability of the harvested bulb.

Key points to remember:

- Garlic grows from cloves, not seeds, ensuring genetic uniformity.

- Vernalization—exposure to cold—is essential for normal bulb development.

- Bulb initiation depends on day length and temperature, varying by cultivar type.

- Hardneck and softneck garlic differ significantly in growth habit, clove arrangement, and climate adaptability.

- Harvest timing and curing determine shelf life and flavor intensity.

- Cooking applications vary based on whether garlic is fresh or cured.

Whether you're a gardener aiming for plump, flavorful bulbs or a cook seeking to understand the origins of your ingredients, recognizing how garlic forms and develops deepens appreciation for this culinary cornerstone. By aligning cultivation practices with natural cycles, we honor both the science and tradition behind one of humanity’s oldest cultivated crops.

Explore seasonal garlic varieties at your local market this summer, or try growing your own next fall. Observe how harvest timing and curing affect flavor—and keep a journal to refine your technique year after year.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?