Dry fasting—a practice that involves abstaining from both food and water—has gained attention in wellness circles for its reported benefits, including improved mental clarity, accelerated autophagy, and enhanced metabolic function. However, because it places significant stress on the body, the frequency and duration of dry fasting must be carefully managed to avoid health risks. Unlike intermittent or water fasting, dry fasting drastically limits hydration, making timing and recovery critical.

The key to safe and effective dry fasting lies not just in how long you fast, but in how often you repeat the process. Overdoing it can lead to dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, kidney strain, and even organ damage. Done correctly, however, it may offer unique physiological advantages. This article outlines evidence-based recommendations, practical schedules, and safety protocols to help you determine the optimal frequency for dry fasting based on your goals and physical condition.

Understanding Dry Fasting: Types and Duration

Dry fasting is typically categorized into two forms:

- Soft dry fasting: Allows minimal contact with water (e.g., brushing teeth, washing face), but no ingestion.

- Hard dry fasting: No water consumption or external contact; a stricter approach.

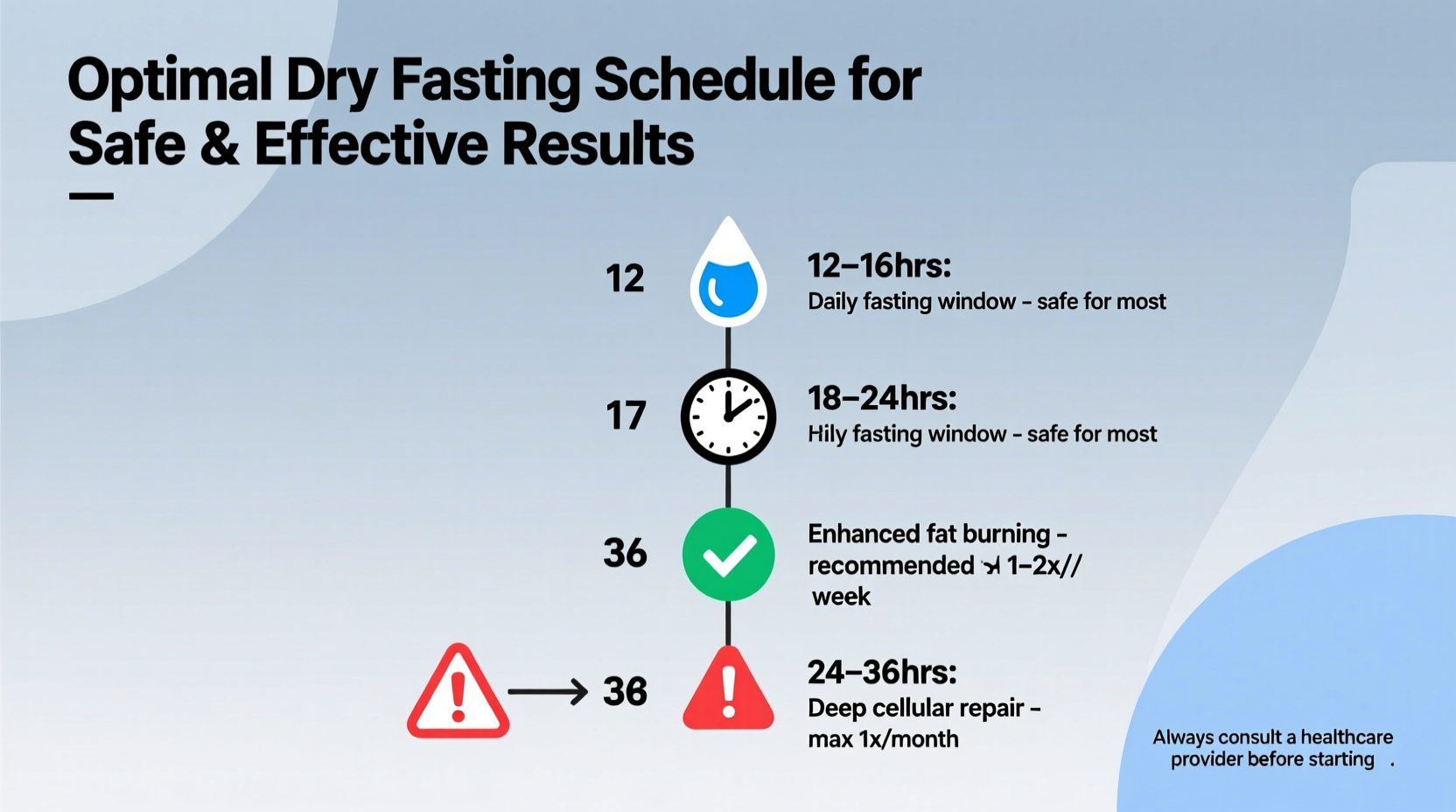

Fasts are further defined by duration:

- Short-term: 12–24 hours – generally safe for most healthy adults.

- Moderate: 24–36 hours – requires preparation and monitoring.

- Extended: 36–72 hours – only recommended for experienced individuals under supervision.

Most experts agree that dry fasts beyond 72 hours carry high risk and are not advised without medical oversight. The human body can survive only about three days without water under ideal conditions, making extended dry fasting extremely dangerous.

Recommended Frequency Based on Experience Level

The frequency of dry fasting should align with your experience, health status, and recovery capacity. Below is a structured guideline:

| Experience Level | Recommended Frequency | Max Duration per Fast | Recovery Time Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginner | Once every 2–4 weeks | 16–24 hours | 3–5 days |

| Intermediate | Once every 1–2 weeks | 24–36 hours | 5–7 days |

| Advanced | Up to twice per month | 36–48 hours | 7–10 days |

It's essential to allow full rehydration and nutrient replenishment between sessions. Repeated short dry fasts without adequate recovery increase the risk of cumulative dehydration and adrenal fatigue.

Step-by-Step Guide to Safe Dry Fasting Cycles

To integrate dry fasting sustainably, follow this six-phase cycle:

- Preparation (2–3 days before): Hydrate well, reduce caffeine and processed foods, and ensure electrolyte balance.

- Entry day: Begin the fast after a light, low-fiber meal. Avoid intense exercise.

- Fasting window: Rest as much as possible. Use meditation or gentle stretching to manage energy levels.

- Breaking the fast: Start with small sips of water, then coconut water or herbal teas. Wait 1–2 hours before eating easily digestible food like steamed vegetables.

- Recovery phase (3–7 days): Prioritize hydration, sleep, and nutrient-dense meals. Avoid alcohol and strenuous activity.

- Monitoring: Track symptoms like dizziness, heart palpitations, or dark urine. Discontinue if warning signs appear.

This cycle ensures that the body enters and exits the fast in a controlled manner, minimizing shock and maximizing potential benefits.

Expert Insight on Safety and Physiology

The physiological impact of dry fasting is profound. Dr. Benjamín Rubio, a Spanish physician and long-time advocate of therapeutic fasting, notes:

“Dry fasting triggers a more rapid autophagic response than water fasting, but it also accelerates dehydration. It should never be used as a weight-loss shortcut—it’s a metabolic reset tool that demands respect.” — Dr. Benjamín Rubio, MD, Fasting Researcher

Autophagy—the body’s cellular cleanup process—may peak earlier during dry fasting due to increased oxidative stress. However, this same stress can become harmful if repeated too frequently. Studies suggest that autophagy activation plateaus after 24–36 hours, meaning longer fasts don’t necessarily yield proportionally greater benefits.

Checklist: Is Your Body Ready for Dry Fasting?

Before starting any dry fast, evaluate your readiness using this checklist:

- ✅ No history of kidney disease, diabetes, or cardiovascular issues

- ✅ Currently well-hydrated (clear or light-yellow urine)

- ✅ Not pregnant, breastfeeding, or under 18

- ✅ Not on medications that affect fluid balance (e.g., diuretics)

- ✅ Experienced with water fasting for at least 24 hours

- ✅ Have a low-stress schedule during and after the fast

- ✅ Access to medical care if needed

If any item is unchecked, reconsider or consult a healthcare provider before proceeding.

Mini Case Study: A Real-World Example

Lena, a 34-year-old yoga instructor and experienced faster, decided to try dry fasting after hearing about its detoxification claims. She had completed multiple 48-hour water fasts with good results. Starting cautiously, she attempted a 20-hour soft dry fast once every three weeks.

Her first fast went smoothly—she meditated, rested, and broke the fast gently. However, on her third attempt, she shortened her recovery period and added a high-intensity training session the day after fasting. She developed severe headaches, fatigue, and dark urine—signs of acute dehydration.

After consulting a functional medicine doctor, Lena adjusted her protocol: extending recovery to five days, increasing electrolyte intake post-fast, and limiting dry fasts to once per month. With these changes, she reported improved focus and digestion without adverse effects.

Her case illustrates that even experienced individuals must respect recovery time and listen to their bodies.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Many people overestimate their tolerance for dry fasting. Common errors include:

- Fasting too often: Attempting weekly dry fasts can impair kidney function over time.

- Breaking the fast too aggressively: Eating heavy or processed foods immediately after can cause nausea and digestive distress.

- Ignoring early warning signs: Dizziness, dry mouth, and reduced urination are red flags.

- Combining with extreme calorie restriction: Post-fast binging or prolonged low-calorie diets hinder recovery.

To mitigate risks, always prioritize gradual progression and bodily feedback over performance metrics.

FAQ

Can I drink anything during a dry fast?

No. By definition, dry fasting excludes all liquid intake, including tea, coffee, and broth. Even small sips disrupt the physiological state targeted by dry fasting.

Is dry fasting better than water fasting?

Not necessarily. While dry fasting may accelerate certain processes like autophagy, it also increases health risks. Water fasting is safer and more sustainable for most people seeking detoxification or metabolic benefits.

Who should never attempt dry fasting?

Pregnant women, individuals with chronic kidney disease, type 1 diabetics, those with a history of eating disorders, and people on prescription medications affecting hydration should avoid dry fasting entirely.

Conclusion: Practice With Caution and Clarity

Dry fasting is not a routine wellness habit but a potent physiological intervention that demands caution, preparation, and self-awareness. For most people, practicing dry fasting once every two to four weeks for 16–24 hours is the safest way to explore its effects. More frequent or longer fasts should only be undertaken by experienced individuals with medical guidance.

The goal isn't to push limits, but to enhance health intelligently. When approached with respect for the body’s needs, dry fasting can be a powerful tool—but only when frequency, duration, and recovery are balanced. Listen to your body, track your responses, and never sacrifice long-term well-being for short-term gains.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?