Consumer surplus is a fundamental concept in economics that measures the benefit consumers receive when they pay less than what they are willing to pay for a good or service. Understanding this metric helps businesses set pricing strategies, governments evaluate policy impacts, and individuals grasp market dynamics. This guide walks through the mechanics of calculating consumer surplus, illustrated with clear explanations and realistic scenarios.

Understanding Consumer Surplus

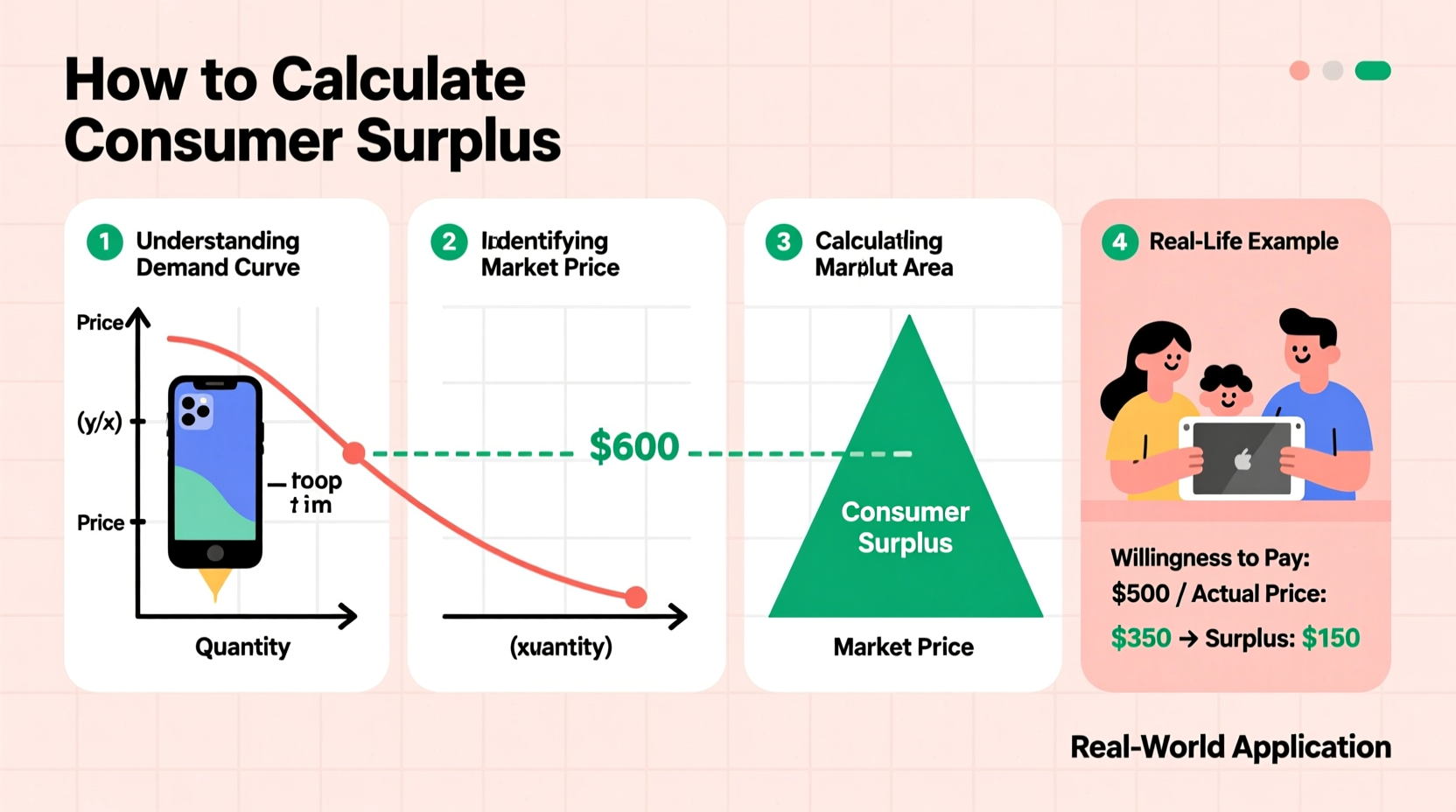

At its core, consumer surplus reflects the difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the actual market price. It represents the extra value or satisfaction gained from a purchase. The concept originates from the law of diminishing marginal utility—each additional unit of a product provides less satisfaction, so willingness to pay decreases as consumption increases.

Graphically, consumer surplus appears as the area above the market price and below the demand curve. In simple terms, if you’d pay $50 for a concert ticket but buy it for $35, your consumer surplus is $15. When aggregated across all buyers, this becomes total consumer surplus in a market.

Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Consumer Surplus

Whether dealing with linear demand curves or discrete data points, the process follows a logical sequence. Below is a structured approach using both graphical and mathematical methods.

- Determine the Demand Curve: Identify the relationship between price and quantity demanded. In basic models, this is often a straight line (linear demand).

- Identify the Market Price: Find the current equilibrium or selling price in the market.

- Find the Quantity Sold at That Price: Use the demand equation to determine how many units are purchased at the given price.

- Locate the Maximum Willingness to Pay: This is the y-intercept of the demand curve—the price at which quantity demanded drops to zero.

- Calculate the Area of the Triangle (for Linear Demand): Use the formula for the area of a triangle: (1/2) × base × height, where the base is the quantity sold and the height is the difference between maximum willingness to pay and market price.

Example: Concert Tickets

Suppose the demand for concert tickets is represented by the equation:

P = 100 – 2Q

Where P is price and Q is quantity. The market price is $40 per ticket.

- Solve for quantity at $40: 40 = 100 – 2Q → 2Q = 60 → Q = 30 tickets sold.

- Maximum willingness to pay (when Q=0): P = 100.

- Height of triangle: 100 – 40 = 60.

- Base of triangle: 30.

- Consumer surplus = (1/2) × 30 × 60 = $900.

This means consumers collectively gain $900 in surplus value from buying these tickets below their maximum willingness to pay.

Real-Life Examples of Consumer Surplus

Case Study: Black Friday Electronics Sale

A major retailer sells wireless headphones with a market price of $80 during a Black Friday promotion. Market research shows that some customers would have paid up to $150. For one customer who values the headphones at $130, the individual consumer surplus is $50. If 10,000 units are sold and average willingness to pay is $110, the average surplus per unit is $30, resulting in a total consumer surplus of $300,000.

This surge in surplus drives high demand on sale days, illustrating how temporary price reductions significantly increase consumer welfare—even if only for a short period.

Everyday Grocery Shopping

Consider a shopper who regularly buys organic avocados. She’s willing to pay up to $3 each but finds them on sale for $2. Her surplus per avocado is $1. Over a month, purchasing 20 avocados at this price yields a monthly surplus of $20. While small individually, these gains accumulate across products and time, improving overall household economic well-being.

“Consumer surplus is not just theoretical—it quantifies real-world satisfaction and purchasing power.” — Dr. Linda Reeves, Behavioral Economist, University of Chicago

Do’s and Don’ts When Calculating Consumer Surplus

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Use accurate demand data from surveys or historical sales. | Assume all consumers have the same willingness to pay. |

| Account for changes in income or preferences over time. | Ignore external factors like seasonality or competition. |

| Apply calculus for non-linear demand curves (integration). | Treat consumer surplus as a static number across markets. |

| Aggregate individual surpluses for market-level analysis. | Forget that surplus can shrink if prices rise unexpectedly. |

Advanced Application: Non-Linear Demand and Integration

Not all demand curves are linear. For more precise modeling—especially in academic or policy settings—calculus is used. Suppose demand is given by:

P = 200 / (Q + 1)

If the market price is $50, solve for Q:

50 = 200 / (Q + 1) → Q + 1 = 4 → Q = 3

To find consumer surplus, integrate the demand function from 0 to 3 and subtract total expenditure:

CS = ∫₀³ (200 / (q + 1)) dq – (50 × 3)

= 200[ln(q+1)] from 0 to 3 – 150

= 200(ln 4 – ln 1) – 150 = 200(ln 4) – 150 ≈ 200(1.386) – 150 ≈ 277.2 – 150 = $127.20

This method provides greater accuracy when demand responds non-uniformly to price changes.

Checklist: How to Accurately Calculate Consumer Surplus

- ✅ Gather reliable data on willingness to pay or historical demand patterns.

- ✅ Plot or define the demand curve (linear or non-linear).

- ✅ Identify the current market price and corresponding quantity.

- ✅ Determine the maximum reservation price (vertical intercept).

- ✅ Apply geometric area formulas or calculus as appropriate.

- ✅ Validate results against real-world observations or survey feedback.

- ✅ Consider elasticity—higher elasticity usually means larger surplus changes with price shifts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can consumer surplus be negative?

No. By definition, consumers won’t purchase a good if the price exceeds their willingness to pay. Thus, consumer surplus is always zero or positive. If someone pays exactly their maximum, surplus is zero—but they still participate.

How does price discrimination affect consumer surplus?

Price discrimination—charging different prices to different consumers—reduces or eliminates consumer surplus. Perfect price discrimination captures the entire surplus as revenue, leaving no extra benefit for buyers. This is common in airline pricing, dynamic e-commerce, and subscription tiers.

Is consumer surplus the same as profit?

No. Consumer surplus benefits buyers; profit benefits sellers. Profit is calculated as total revenue minus costs. Confusing the two can lead to flawed business decisions. A high consumer surplus doesn’t imply low profit—it may indicate strong demand and scalability.

Conclusion: Putting Consumer Surplus Into Practice

Calculating consumer surplus isn't just an academic exercise—it has tangible implications for pricing, marketing, and public policy. Businesses can use it to gauge customer satisfaction and optimize discounts. Policymakers assess tax impacts or subsidy effectiveness through changes in consumer surplus. Individuals can even apply the concept mentally when evaluating deals or bulk purchases.

By mastering this tool, you gain insight into the invisible value exchanged in every transaction. Whether analyzing a coffee shop’s loyalty program or a government housing initiative, understanding surplus reveals the true depth of economic well-being beyond mere price tags.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?