Bird flu, or avian influenza, is a highly contagious viral disease that affects both wild and domesticated birds. While some strains cause mild illness, others—like the H5N1 subtype—can lead to rapid death in entire flocks. For backyard poultry keepers, pet bird owners, and small-scale farmers, recognizing the early signs of infection is critical to containing outbreaks and preventing transmission to other birds—and potentially humans. This guide equips you with the knowledge to detect symptoms quickly, respond effectively, and implement preventive strategies.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Types and Transmission

Avian influenza viruses are classified into two main categories based on their pathogenicity: low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) and high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). LPAI often causes mild or no symptoms, making it easy to overlook. However, certain LPAI strains can mutate into HPAI, which spreads rapidly and results in high mortality rates—sometimes killing up to 90–100% of infected birds within 48 hours.

The virus primarily spreads through direct contact with infected birds, their droppings, or contaminated surfaces such as feeders, waterers, and footwear. Wild waterfowl, especially ducks and geese, often carry the virus without showing symptoms, acting as silent carriers. Airborne transmission over short distances is also possible in enclosed spaces like coops.

“Early detection saves lives. By the time severe symptoms appear, the virus may have already spread through the flock.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Avian Health Specialist, National Poultry Research Center

Common Symptoms of Bird Flu in Domestic Birds

Symptoms vary depending on the strain, species, and overall health of the bird. Chickens and turkeys tend to show more severe signs than ducks or geese, which may remain asymptomatic while still shedding the virus.

Key clinical signs include:

- Sudden death – Often the first noticeable sign, especially with HPAI. Birds may be found dead without prior visible illness.

- Respiratory distress – Gasping, coughing, sneezing, nasal discharge, and swollen sinuses.

- Neurological issues – Tremors, twisted necks (torticollis), circling, or lack of coordination.

- Drop in egg production – A sudden decline or complete cessation of laying, sometimes with soft-shelled or misshapen eggs.

- Swelling and discoloration – Bluish or purple discoloration of combs, wattles, legs, and around the eyes due to poor circulation.

- Lethargy and isolation – Affected birds often sit hunched, fluffed up, and avoid interaction.

- Reduced appetite and water intake – Leading to rapid weight loss and dehydration.

- Diarrhea – Often greenish or watery, contributing to soiled feathers and coop contamination.

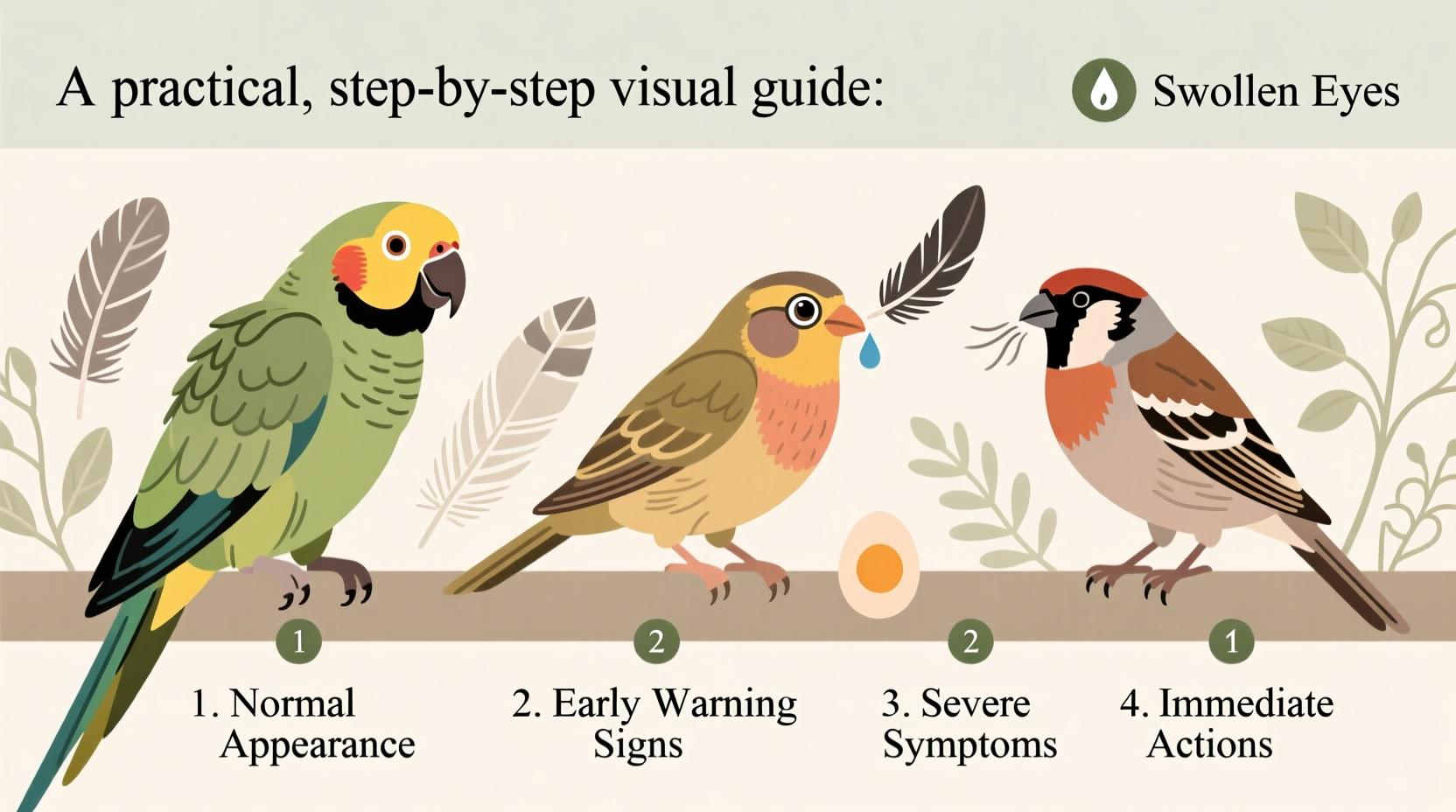

Step-by-Step Guide to Monitoring and Responding to Suspected Cases

If you suspect bird flu in your flock, immediate action is essential. Follow this timeline to contain the situation:

- Isolate sick birds immediately – Move affected individuals to a separate, secure area with dedicated tools and feeding equipment.

- Limit human and animal traffic – Restrict access to the coop. Wear gloves and disposable coveralls when handling sick birds.

- Contact a veterinarian or state animal health authority – Do not attempt home diagnosis. Many diseases mimic bird flu; only lab testing can confirm it.

- Begin biosecurity protocols – Disinfect shoes, clothing, and equipment. Use a 1:10 bleach solution or veterinary-grade disinfectant.

- Monitor remaining birds closely – Watch for new symptoms over the next 7–10 days.

- Dispose of carcasses safely – Double-bag and follow local regulations for disposal. Never compost or bury near water sources.

- Await test results and follow official guidance – If confirmed, depopulation may be required to stop further spread.

Do’s and Don’ts During a Suspected Outbreak

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Wash hands before and after handling birds | Allow visitors near your birds without protective gear |

| Clean and disinfect coops weekly | Share equipment between flocks |

| Report sick or dead birds promptly | Transport live birds from affected areas |

| Use footbaths with disinfectant at coop entrances | Handle dead birds with bare hands |

| Keep wild birds away from feed and water sources | Assume mild symptoms aren't serious |

Real-World Example: A Backyard Flock Case Study

In spring 2023, a small poultry keeper in rural Indiana noticed three of her eight chickens had stopped laying and appeared listless. One died overnight. Initially, she assumed it was heat stress. But when two more birds developed swollen combs and began gasping, she isolated them and called her vet.

The veterinarian collected swabs and reported the case to the state department. Testing confirmed HPAI H5N1. The remaining five birds were humanely euthanized under supervision, and the coop was disinfected using USDA-recommended protocols. Because she acted quickly and followed containment procedures, the outbreak did not spread to neighboring farms. Her prompt response likely prevented regional contamination.

This case underscores the importance of vigilance—even minor behavioral shifts warrant investigation when bird flu is circulating in your region.

Prevention Checklist for Bird Owners

Prevention is far more effective than reaction. Use this checklist to strengthen your biosecurity:

- ✅ Secure enclosures to prevent contact with wild birds

- ✅ Provide clean, fresh water and store feed in sealed containers

- ✅ Rotate or rest run areas to reduce pathogen buildup

- ✅ Quarantine new birds for at least 30 days before introducing them

- ✅ Avoid visiting other poultry sites—or if necessary, change clothes and shower afterward

- ✅ Install netting or covers over outdoor runs during peak migration seasons

- ✅ Register your flock with the USDA or local agricultural office for disease alerts

- ✅ Keep emergency contact numbers handy: vet, state animal health official, USDA hotline

Frequently Asked Questions

Can humans get bird flu from their pets or chickens?

Yes, though rare. Most human cases result from prolonged, close contact with infected birds—especially during slaughter or handling of raw carcasses. The CDC advises wearing masks and gloves when dealing with sick or dead poultry. Human-to-human transmission is extremely uncommon.

Are there vaccines for bird flu in backyard flocks?

Vaccines exist but are not widely available for small-scale owners. Their use is typically restricted to commercial operations under government programs. Vaccination does not eliminate the virus but may reduce symptoms and shedding. Prevention through biosecurity remains the primary defense.

What should I do if I find a dead wild bird in my yard?

Do not touch it with bare hands. Report it to your local wildlife agency or state department of natural resources. They will advise whether testing is needed, especially if multiple birds are involved or waterfowl are present.

Conclusion: Protect Your Flock, Protect Your Community

Identifying bird flu symptoms early isn’t just about saving individual birds—it’s about protecting your entire operation and the wider avian population. With heightened global surveillance and increasing outbreaks linked to migratory patterns, every bird owner plays a role in early detection and containment. By staying informed, practicing strict hygiene, and responding swiftly to warning signs, you create a safer environment for your birds and contribute to broader disease control efforts.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?