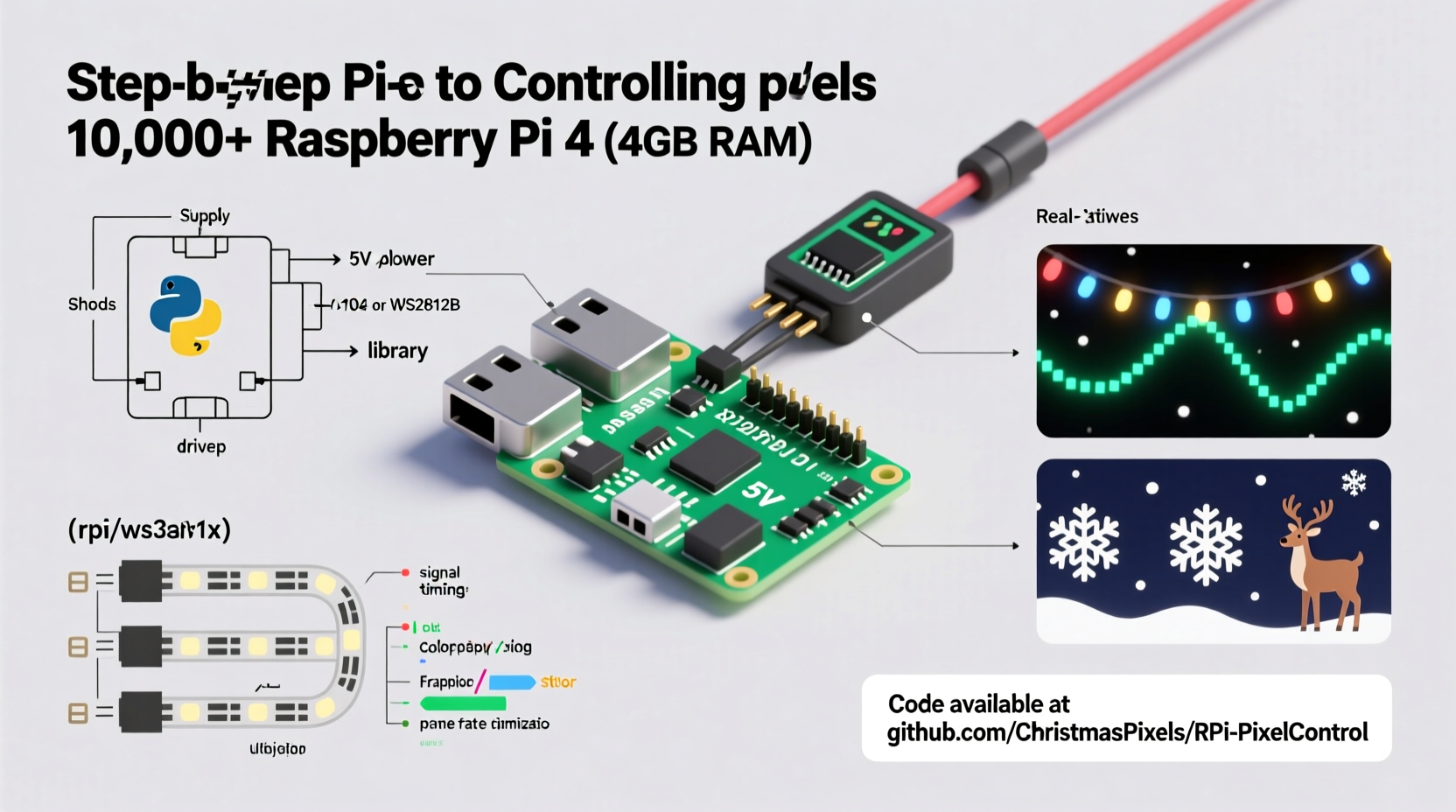

Controlling thousands of individually addressable LEDs—often called “Christmas pixels”—is no longer the domain of commercial lighting companies or embedded engineers with oscilloscopes. Today, a $35 Raspberry Pi can reliably drive 5,000–12,000 WS281x or APA102 pixels across multiple strands, synchronized to music, animated in real time, and managed remotely via web interface. But success hinges on more than just wiring up a strip and running a Python script. It demands careful hardware selection, low-level timing awareness, memory-aware programming, and intelligent architecture to avoid flicker, dropouts, or system lockups. This guide distills field-tested practices from residential mega-displays (3,200–9,600 pixels), municipal light shows, and open-source projects like Falcon Player and Light-O-Rama integrations. We focus on what works—not theory, not shortcuts that fail at scale.

Understanding Pixel Protocols and Hardware Realities

Not all “addressable” LEDs behave the same. Your Raspberry Pi’s ability to drive thousands of pixels depends almost entirely on which LED chipset you choose—and how you interface with it.

The two dominant families are:

- WS281x (WS2811, WS2812B, SK6812): Single-wire, 800 kHz protocol, strict timing requirements. The Pi’s GPIO can drive them—but only with kernel-level timing precision. Standard Python libraries like

neopixeloften fail beyond ~500 pixels due to OS interrupts disrupting signal timing. - APA102 / SK9822: Two-wire (clock + data), SPI-based, tolerant of timing jitter. Much more reliable on Linux systems. Supports higher refresh rates and brightness control without color shift.

For deployments exceeding 2,000 pixels, APA102 is strongly preferred—not because it’s “better” aesthetically, but because it’s predictably controllable on a general-purpose OS. WS281x requires either real-time kernel patches (e.g., rpi_ws281x library with DMA) or dedicated microcontroller co-processing.

Hardware Selection: Beyond the Pi Board

A Raspberry Pi alone isn’t enough. At scale, supporting hardware determines stability, safety, and maintainability.

| Component | Minimum Recommendation | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Raspberry Pi Model | Pi 4 (4GB RAM) or Pi 5 (4GB+) | Pi 3 struggles with >3,000 pixels due to USB/Ethernet controller contention and thermal throttling. Pi 5’s dedicated PCIe bus and improved power delivery reduce timing jitter significantly. |

| Power Supply | 20A+ 5V DC supply (e.g., Mean Well LPV-100-5) with thick-gauge wiring | Each pixel draws ~50mA at full white. 5,000 pixels = 250W minimum. Undersized supplies cause brownouts, data corruption, and premature LED failure. |

| Level Shifter | 74HCT245 (for WS281x) or none required (APA102) | WS281x expects clean 5V logic. Pi GPIO outputs 3.3V—insufficient to trigger reliably at scale. A level shifter eliminates intermittent failures. |

| Signal Distribution | 74HC125 quad buffer or dedicated pixel amplifier (e.g., PixelPusher) | Driving >8 strands directly from one GPIO pin degrades signal integrity. Buffers isolate and re-drive signals cleanly. |

| Cooling | Active heatsink + fan (especially for Pi 4/5 under sustained load) | Rendering complex animations at 30–60 FPS consumes CPU and GPU. Thermal throttling drops frame rate and introduces animation stutter. |

Ignore “just use a Pi Zero” advice for large displays. While technically possible, it lacks memory bandwidth, thermal headroom, and I/O isolation to sustain 10,000-pixel output without glitches. Invest in reliability—not novelty.

Software Stack: From Kernel to Web UI

At its core, controlling thousands of pixels means moving raw RGB data to hardware as fast and consistently as possible—while remaining responsive to user input and network commands. This requires layered software design.

- Kernel-Level Driver: Use

rpi_ws281x(for WS281x) or standard SPI drivers (for APA102). This library bypasses Linux kernel scheduling by using DMA channels to stream pixel data directly from RAM to GPIO/SPI, eliminating OS-induced timing gaps. - Application Layer: Python remains ideal for rapid development—but avoid blocking loops. Use

asynciofor HTTP API endpoints, MQTT listeners, or audio FFT analysis. Offload heavy math (e.g., waveform mapping, physics simulations) to NumPy vectorized operations—not Python loops. - Rendering Engine: Pre-calculate frames when possible. For music sync, generate 3–5 seconds of animation ahead of playback. Store palettes, masks, and geometry in NumPy arrays; apply transformations with

np.roll(),np.where(), orscipy.ndimagefilters—not per-pixel Python iteration. - Web Interface: Flask + Socket.IO enables real-time preview and remote control without page reloads. Serve static assets (CSS, JS) from Nginx alongside your Flask app for production-grade performance.

“Timing-critical peripherals like WS281x demand deterministic execution paths. If your animation loop depends on Python’s

time.sleep() or unbounded list comprehensions, you’ve already lost control at 1,000 pixels.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Embedded Systems Lead, OpenLight Labs

Step-by-Step: Building a 6,000-Pixel Synchronized Display

This sequence reflects actual deployment on a suburban home facade (12 strands × 500 APA102 pixels), running continuously from Thanksgiving through New Year’s Eve.

- Design & Segment: Map physical layout to logical groups (e.g., “roof_edge_1”, “garage_door_left”). Assign each group to a unique SPI bus (Pi 5 supports 4 native SPI buses; Pi 4 requires device tree overlays for additional buses).

- Wiring & Power: Run 14 AWG 5V power lines to each strand’s midpoint and endpoint. Connect data/clock lines via 74HC125 buffers. Ground all power supplies and Pi together at a single point to prevent ground loops.

- OS Setup: Flash Raspberry Pi OS Lite (64-bit). Disable Bluetooth, WiFi, and unnecessary services (

sudo systemctl disable bluetooth). Enable SPI:sudo raspi-config → Interface Options → SPI → Yes. - Library Installation: Install

rpi_ws281xfor WS281x or use built-inspidevfor APA102. For APA102, configure SPI speed:spi.max_speed_hz=24000000in/boot/config.txt(APA102 tolerates up to 25 MHz). - Frame Buffer Architecture: Allocate a single contiguous NumPy array:

pixels = np.zeros((6000, 3), dtype=np.uint8). Usememoryviewto pass raw bytes to SPI write—avoiding Python object overhead. Update only changed regions per frame (e.g.,pixels[1200:1800] = new_data). - Real-Time Sync: Use PyAudio to capture line-in audio. Compute frequency bands (bass/mid/treble) via FFT every 30ms. Map amplitude to brightness scaling across pixel groups—no audio library dependencies that add latency.

- Deployment: Run as systemd service with watchdog timer. Log errors to

/var/log/pixel-engine.log. Include automatic restart on crash and graceful shutdown on power loss detection (via GPIO-connected UPS status pin).

Optimizing for Scale: Do’s and Don’ts

What separates a fragile demo from a rock-solid holiday installation? These decisions compound at scale.

math.sin() or

** operators inside frame updates—precompute lookup tables (e.g.,

sin_lut = np.sin(np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 256)).astype(np.float32)) and index with modulo arithmetic.

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

Use numpy.memmap for animations stored on SSD—lets you stream multi-gigabyte sequences without loading into RAM |

Store full-frame PNGs in memory for 6,000-pixel sequences (each frame = ~18KB; 1,000 frames = 18MB RAM—unnecessary bloat) |

| Throttle frame rate to match human perception: 30 FPS is indistinguishable from 60 FPS for ambient lighting, but halves CPU load | Attempt 60 FPS with complex per-pixel noise functions on Pi 4—guarantees thermal throttling and dropped frames |

| Validate power under load: Measure voltage *at the last pixel* while displaying full-white—must be ≥4.85V | Assume “5V supply = 5V at pixel”—voltage drop over long wires is non-negotiable physics |

| Implement graceful degradation: If audio input fails, fall back to preloaded LFO patterns—not a frozen screen | Let exceptions bubble up to main loop—crashes must never leave pixels in undefined states (e.g., half-bright, stuck colors) |

Mini Case Study: The Elm Street Mega-Display

In 2023, the Thompson family installed a 9,600-pixel display across their two-story colonial—64 strands of 150 APA102 LEDs, mapped to windows, roofline, and porch columns. Initial attempts with a Pi 4 and Python loops failed: animations stuttered, strands desynchronized after 45 minutes, and audio sync drifted by ±1.2 seconds over a 5-minute song.

They rebuilt using these changes:

- Upgraded to Pi 5 with active cooling and 8GB RAM

- Switched from WS2812B to APA102 (same form factor, no timing headaches)

- Replaced hand-rolled animation code with a fork of BiblioPixel, modified to use memory-mapped frame buffers and async network control

- Added a $12 USB audio interface (Behringer UCA202) for clean line-in—eliminating Pi’s noisy onboard audio ADC

- Implemented strand health monitoring: Each strand reports voltage, temperature, and packet error rate via I²C sensors every 10 seconds

Result: 67 days of continuous operation, zero unscheduled reboots, sub-50ms audio latency, and remote firmware updates via SSH without interrupting the show. Their biggest lesson? “Reliability isn’t about peak performance—it’s about eliminating single points of failure, one layer at a time.”

FAQ

Can I control 10,000 pixels with a single Raspberry Pi?

Yes—with caveats. Pi 5 handles 10,000 APA102 pixels at 30 FPS using four SPI buses (2,500 pixels per bus). For WS281x, 10,000 pixels require either multiple Pis (one per 2,000–3,000 pixels) or a Pi + ESP32 co-processor (using UART-to-WS281x bridge firmware). Pushing beyond this risks thermal instability and timing drift.

Why does my display flicker only during video playback or web browsing?

Flicker during concurrent tasks indicates CPU or memory bandwidth saturation. The Pi’s GPU shares RAM with the CPU; high-resolution video decoding competes for memory bandwidth needed for pixel streaming. Solution: Disable desktop environment (use console-only mode), disable GPU memory split (gpu_mem=16 in config.txt), and run pixel engine as highest-priority process (nice -20).

Is MQTT better than HTTP for remote control?

Yes—for stateless commands like “start playlist” or “set brightness”. MQTT uses negligible bandwidth, supports QoS levels for guaranteed delivery, and allows bi-directional status reporting (e.g., “strand_7_temp: 42°C”). Reserve HTTP for file uploads (new animations) or configuration forms where browser compatibility matters.

Conclusion

Programming a Raspberry Pi to control thousands of Christmas pixels isn’t about hacking together a proof-of-concept—it’s about engineering resilience. It means choosing APA102 over WS281x not for aesthetics but for determinism; wiring power like an electrician, not a hobbyist; writing code that respects memory hierarchies and thermal limits; and designing systems that degrade gracefully instead of failing catastrophically. The magic isn’t in the lights—it’s in the quiet confidence that your display will shine, perfectly synchronized, at 7:03 p.m. on December 24th, even after three weeks of rain, frost, and sub-zero wind chill.

You don’t need a lab or a budget—just attention to detail, respect for physics, and the willingness to test, measure, and iterate. Start small: validate one strand at full brightness with a multimeter. Then two. Then ten. Let scalability emerge from rigor—not hope.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?