For many individuals living with emotional or medical conditions, a support dog can be more than a companion—it can be a lifeline. These animals provide critical assistance, from interrupting panic attacks to detecting oncoming seizures. Yet the process of qualifying for and acquiring a support dog is often misunderstood. Unlike regular pets, support dogs are protected under U.S. law, but they must meet specific criteria. This guide walks through every phase: understanding eligibility, navigating legal frameworks, choosing the right type of dog, and ensuring proper training and integration into daily life.

Understanding Support Dogs: Types and Legal Definitions

Before beginning the process, it’s essential to distinguish between types of support animals recognized in the United States:

- Service Dogs: Individually trained to perform tasks for people with disabilities (e.g., guiding the visually impaired, alerting to seizures). Protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- Emotional Support Animals (ESAs): Provide comfort through companionship but are not task-trained. Covered under the Fair Housing Act (FHA) and Air Carrier Access Act (though airline policies have tightened).

- Therapy Dogs: Trained to provide affection and comfort to multiple people in settings like hospitals or schools. Not granted public access rights.

The term “support dog” typically refers to either a service dog or an ESA, depending on context. For full public access rights—including entry to restaurants, stores, and public transit—a dog must be a trained service animal under ADA guidelines.

“Not all dogs that help with anxiety or depression are service animals. The key distinction is whether the dog is trained to perform a specific task directly related to the disability.” — Dr. Rebecca Johnson, Director, Research Center for Human-Animal Interaction

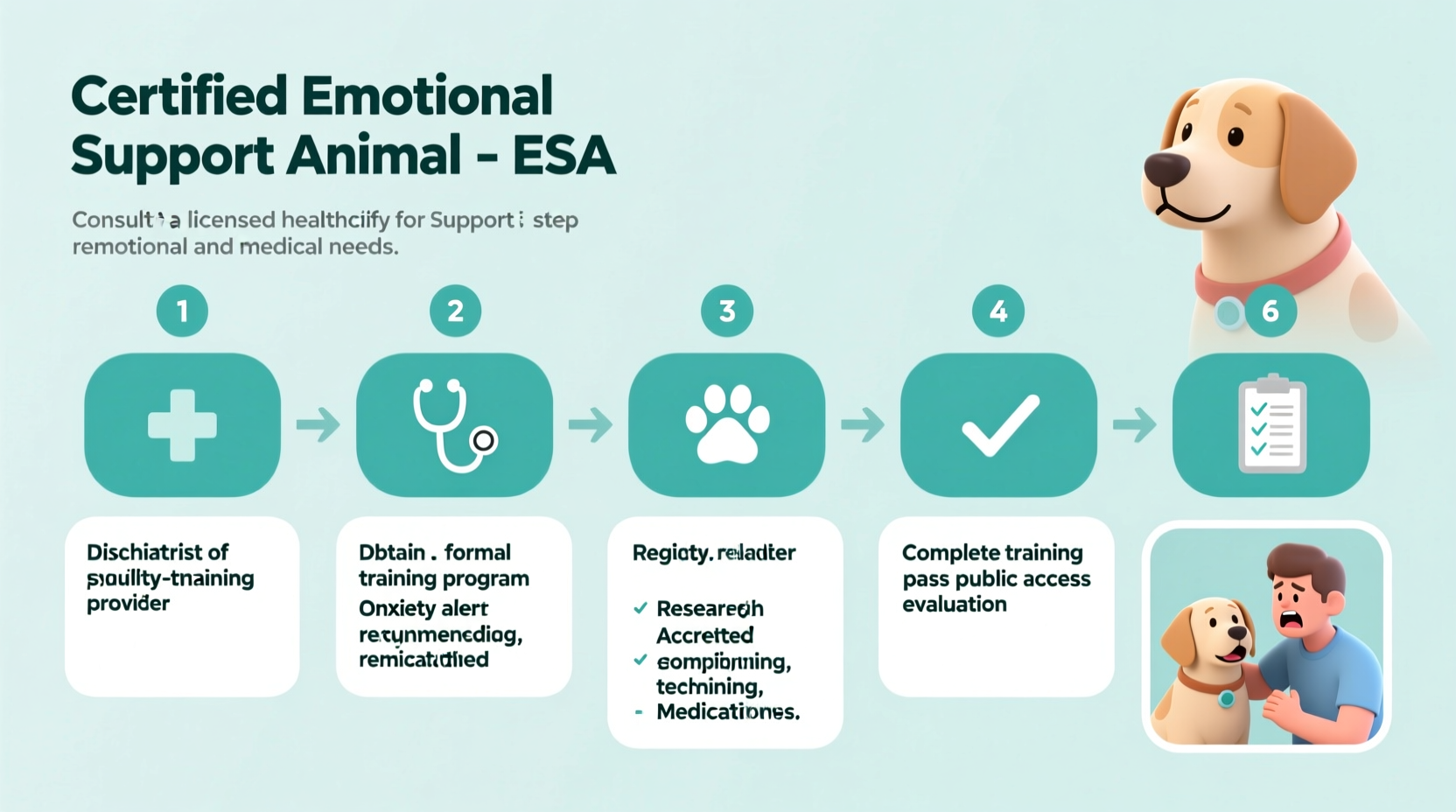

Step-by-Step Path to Qualifying for a Support Dog

Obtaining a support dog involves medical, legal, and practical steps. Follow this timeline to ensure compliance and success.

- Assess Your Need: Determine whether your condition significantly limits one or more major life activities. Common qualifying conditions include PTSD, severe anxiety, depression, diabetes, epilepsy, and mobility impairments.

- Consult a Licensed Mental Health or Medical Professional: Only a licensed therapist, psychologist, or physician can diagnose a disability and recommend a support animal. For ESAs, you’ll need an ESA letter; for service dogs, a diagnosis is required, but no formal letter is needed under ADA.

- Determine the Type of Support Dog You Need: If you require intervention during medical episodes (e.g., seizure response), a service dog is appropriate. If you need constant emotional comfort but no task performance, an ESA may suffice—though with fewer access rights.

- Acquire a Dog Suitable for Training: Choose a breed and temperament aligned with your lifestyle and needs. Some opt to adopt from shelters; others work with breeders or specialized programs.

- Train the Dog (or Work with a Program): Service dogs must be task-trained. Self-training is allowed, but many use accredited organizations. ESAs do not require formal training but should be well-behaved.

- Register (Optional) and Document: While registration isn’t legally required, some owners use voluntary registries for convenience. Always carry documentation, especially an ESA letter if applicable.

- Integrate the Dog Into Daily Life: Practice public outings, manage veterinary care, and maintain ongoing training.

Do’s and Don’ts When Pursuing a Support Dog

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Work with licensed healthcare providers for evaluation and documentation. | Buy “certification” kits online—these have no legal standing. |

| Invest time in obedience and task-specific training. | Assume all landlords or airlines will accept informal claims without proof. |

| Choose a dog with a calm temperament and health clearance. | Use your support dog as a status symbol or allow uncontrolled behavior in public. |

| Maintain public etiquette: keep your dog leashed, clean, and non-disruptive. | Attempt to bring an untrained dog into public spaces claiming ADA protection. |

Real-Life Example: Sarah’s Journey to Getting a PTSD Service Dog

Sarah, a military veteran, struggled with severe PTSD after returning from deployment. Despite therapy and medication, she experienced frequent nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance of public spaces. Her psychologist diagnosed her with a disabling condition and suggested a service dog could help.

She applied to a nonprofit that trains service dogs for veterans. After a six-month wait and home assessment, she was paired with Max, a Labrador Retriever trained to perform grounding techniques during anxiety attacks, create physical space in crowded areas, and wake her from nightmares. Over three weeks, Sarah underwent handler training alongside Max. Today, Max accompanies her to grocery stores, doctor appointments, and family events—something she couldn’t have imagined before.

Sarah emphasizes that the process took patience and commitment. “Max didn’t fix everything overnight,” she says. “But he gave me back my independence.”

Checklist: Preparing for Your Support Dog

- ☑ Obtain a formal diagnosis from a licensed mental health or medical professional.

- ☑ Decide between a service dog and an emotional support animal based on your functional needs.

- ☑ Research reputable trainers or nonprofit programs if self-training isn’t feasible.

- ☑ Budget for initial and ongoing costs (adoption, training, vet care, equipment).

- ☑ Secure an ESA letter (if applicable) on official letterhead with license number.

- ☑ Begin basic obedience training or enroll in a structured program.

- ☑ Practice public access skills in low-stress environments before relying on the dog in critical situations.

- ☑ Understand housing and travel rights—and responsibilities—under federal law.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I train my current dog to be a service dog?

Yes, provided the dog is physically capable, emotionally stable, and able to learn specific tasks. Many pet dogs transition successfully into service roles with proper training. However, not all dogs have the temperament for public work.

How much does it cost to get a support dog?

Costs vary widely. Adopting and training a dog yourself may cost $500–$2,000. Working with a nonprofit may be free or low-cost, though waiting lists are long. Private training programs can charge $15,000–$30,000. ESAs generally only require vet care and an ESA letter (typically $100–$200).

Do I need to register my service dog?

No. The ADA does not require registration, ID cards, or vests. Fraudulent online registries exploit this misconception. Legitimate access is based on behavior and necessity, not paperwork.

Final Steps and Moving Forward

Qualifying for and obtaining a support dog is a journey that blends medical validation, dedicated training, and legal awareness. Whether you’re seeking relief from chronic anxiety, managing a neurological condition, or regaining confidence after trauma, a well-trained support dog can transform your daily experience.

The most successful outcomes come from realistic expectations, consistent training, and partnership—not ownership. A support dog is not a cure, but a tool that, when used correctly, empowers individuals to live more fully.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?