Hemochromatosis, often referred to as hereditary hemochromatosis, is a genetic disorder that causes the body to absorb and store excessive amounts of iron. Over time, this excess iron accumulates in vital organs like the liver, heart, and pancreas, potentially leading to severe damage. What makes hemochromatosis particularly dangerous is its silent progression—many people experience no symptoms until significant organ damage has occurred. Recognizing the early signs and knowing when to seek testing can be life-saving.

Understanding Hemochromatosis: The Basics

Iron is essential for producing hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. However, when the body absorbs too much iron due to a genetic mutation—most commonly in the HFE gene (C282Y or H63D)—the excess isn’t efficiently excreted. Instead, it builds up over years, sometimes decades. This condition affects approximately 1 in 200 to 300 people of Northern European descent, though it’s underdiagnosed because early symptoms are nonspecific and often mistaken for other conditions.

The primary form, hereditary hemochromatosis, is autosomal recessive, meaning both parents must pass on a defective gene for the disease to manifest. Secondary hemochromatosis can result from chronic blood transfusions, certain anemias, or long-term liver disease, but it’s less common than the inherited type.

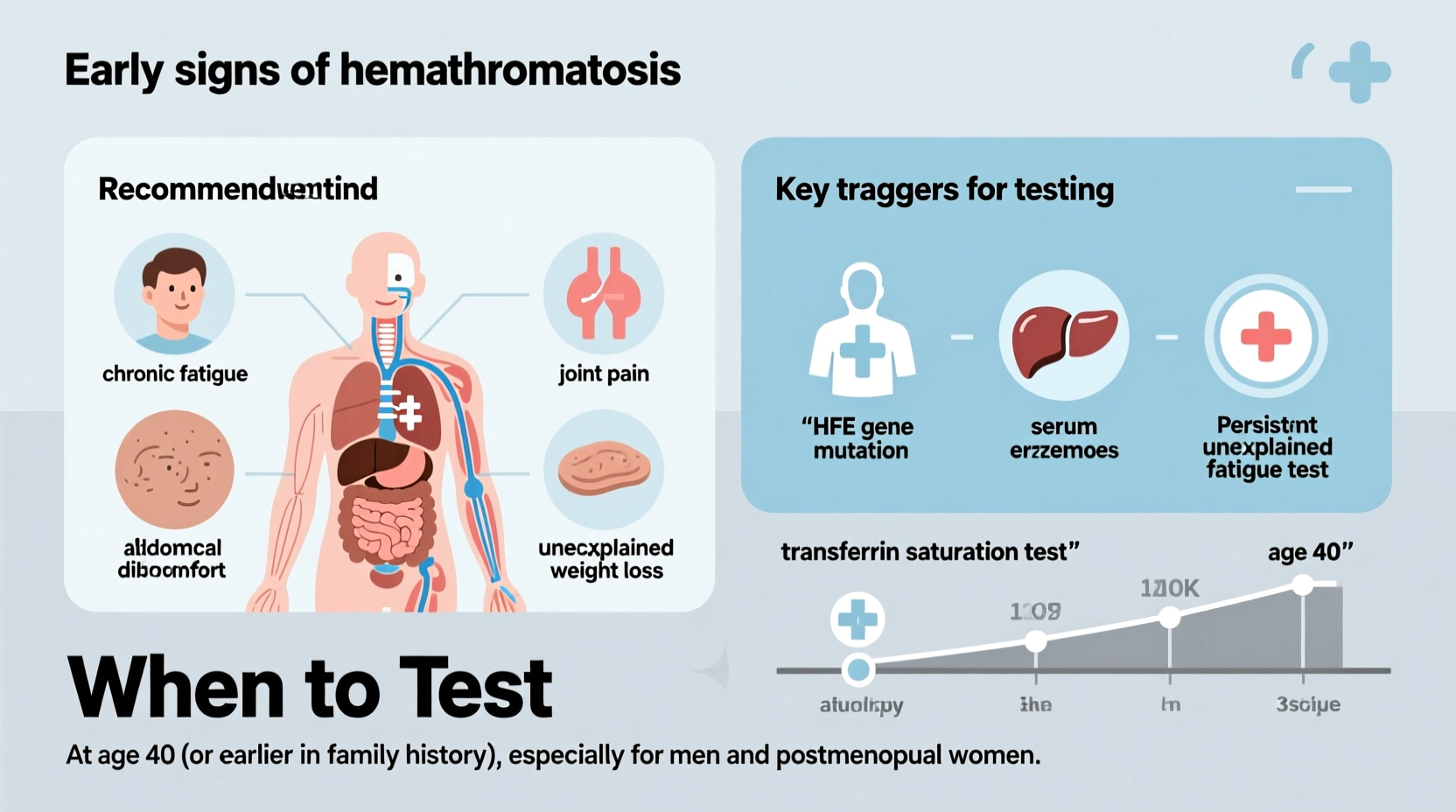

Early Signs and Symptoms to Watch For

In the initial stages, hemochromatosis mimics everyday health complaints, making it easy to overlook. Symptoms typically emerge between ages 30 and 50 in men and after menopause in women, as menstruation offers some natural protection by reducing iron levels. Key early indicators include:

- Chronic fatigue and weakness

- Joint pain, especially in the knuckles (often called “iron fist”)

- Abdominal discomfort or pain in the liver area (upper right abdomen)

- Loss of libido or erectile dysfunction

- Irregular or absent menstrual periods

- Skin discoloration—bronze, gray, or yellowish tint

- Unexplained weight loss

These symptoms are often dismissed as stress, aging, or other common ailments. However, their combination—especially joint pain with fatigue—should prompt further investigation.

“Many patients come in with vague symptoms like tiredness and joint aches, only to discover they’ve had iron overload for years. Early testing could have prevented irreversible organ damage.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Hepatologist at Boston General Hospital

When Should You Get Tested?

Testing for hemochromatosis is simple and non-invasive, involving blood tests to measure iron levels. The two key markers are:

- Serum ferritin: Reflects total iron stores in the body.

- Transferrin saturation (TSAT): Measures how much iron is bound to transferrin, the protein that transports iron in the blood.

Elevated levels of both suggest iron overload. If results are abnormal, genetic testing can confirm the presence of HFE mutations.

Who Should Be Tested?

Certain individuals should strongly consider screening, even without symptoms:

- First-degree relatives of someone diagnosed with hemochromatosis—siblings, parents, or children have a 25% chance of inheriting two defective genes.

- Men over 30 and postmenopausal women with persistent fatigue or joint pain.

- People with liver abnormalities such as elevated liver enzymes or fatty liver without clear cause.

- Those with unexplained diabetes, heart arrhythmias, or hypogonadism, as iron overload can impair these systems.

- Individuals of Irish, Scottish, Welsh, English, or Scandinavian descent, where the gene mutation is more prevalent.

Step-by-Step Guide to Diagnosis and Management

If you suspect hemochromatosis, follow this sequence to ensure timely diagnosis and care:

- Track your symptoms: Keep a journal of fatigue, joint pain, skin changes, or digestive issues for at least two weeks.

- Consult your primary care provider: Share your symptom log and family history. Request serum ferritin and transferrin saturation tests.

- Review lab results: TSAT above 45% and ferritin over 300 ng/mL (men) or 200 ng/mL (women) warrant further evaluation.

- Genetic testing: If iron markers are high, ask for HFE gene testing to confirm hereditary hemochromatosis.

- Refer to a specialist: A hepatologist, hematologist, or endocrinologist can guide treatment, which usually begins with therapeutic phlebotomy (regular blood removal).

- Begin treatment: Weekly or biweekly blood draws reduce iron stores gradually. Once normal levels are reached, maintenance phlebotomy may continue every few months.

- Monitor regularly: Annual ferritin checks help ensure iron doesn’t accumulate again.

Risks of Delayed Diagnosis: A Real-Life Example

John, a 47-year-old software engineer of Irish descent, visited his doctor complaining of constant tiredness and sore hands. He’d been attributing his fatigue to long work hours and assumed his joint pain was early arthritis. His routine blood work didn’t include iron testing. Over the next three years, he developed darkening skin, irregular heartbeats, and rising liver enzymes. Only after being hospitalized for arrhythmia was he tested for iron overload. His ferritin level was over 2,000 ng/mL—ten times the normal limit. A liver biopsy revealed cirrhosis. Genetic testing confirmed he had two copies of the C282Y mutation.

With timely diagnosis and treatment starting a decade earlier, John could have avoided permanent liver damage. His case underscores how easily early signs are missed—and why proactive testing matters.

Do’s and Don’ts for Managing Iron Levels

| Do | Avoid |

|---|---|

| Get regular blood tests if at risk | Ignore persistent fatigue or joint pain |

| Donate blood regularly (if approved) | Take iron supplements or vitamin C with meals |

| Eat a balanced diet low in red meat | Consume raw shellfish (risk of infection when iron overloaded) |

| Inform family members about genetic risks | Drink excessive alcohol, which accelerates liver damage |

| Follow prescribed phlebotomy schedules | Assume normal CBC means normal iron levels |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you have hemochromatosis without symptoms?

Yes. Many people remain asymptomatic for years despite high iron levels. This is why family screening and early testing are critical—even without symptoms, organ damage can progress silently.

Is hemochromatosis treatable?

Yes, and very effectively when caught early. Therapeutic phlebotomy removes excess iron and can prevent complications like liver failure, diabetes, and heart disease. Most patients who begin treatment before organ damage occurs have a normal life expectancy.

Can lifestyle changes help manage hemochromatosis?

They can support medical treatment. Avoiding iron-rich foods (like red meat and fortified cereals), not taking iron or vitamin C supplements, limiting alcohol, and avoiding raw seafood reduce iron absorption and infection risk. However, phlebotomy remains the cornerstone of therapy.

Conclusion: Take Action Before Damage Occurs

Hemochromatosis doesn’t announce itself loudly. Its early signs are subtle, common, and easily misattributed. Yet left unchecked, it can lead to irreversible harm. The good news is that it’s one of the most treatable genetic disorders—if detected early. Knowing your family history, recognizing the warning signs, and advocating for proper testing are powerful steps toward protecting your long-term health.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?