Eating disorders are serious mental health conditions that affect millions worldwide, cutting across age, gender, and background. Often misunderstood as lifestyle choices or phases, they are in fact complex illnesses rooted in psychological, biological, and social factors. The earlier a person receives support, the greater their chances of recovery. Recognizing subtle behavioral, emotional, and physical changes can make all the difference. This guide outlines key warning signs, provides practical steps for intervention, and directs you to trusted resources for professional help.

Understanding Eating Disorders: More Than Just Food

Eating disorders—including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder (BED), and other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED)—are not about vanity or willpower. They often develop as coping mechanisms for underlying emotional distress, trauma, anxiety, or perfectionism. While disordered eating behaviors vary, they commonly involve an unhealthy preoccupation with food, body weight, shape, or control.

According to the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA), at least 30 million people in the U.S. will experience an eating disorder in their lifetime. Despite their prevalence, only one in ten individuals receive treatment—often due to lack of awareness or stigma.

“Eating disorders thrive in silence. The most powerful thing someone can do is speak up—not just for themselves, but for others who may be too afraid to.” — Dr. Cynthia M. Bulik, Professor of Eating Disorders Research, University of North Carolina

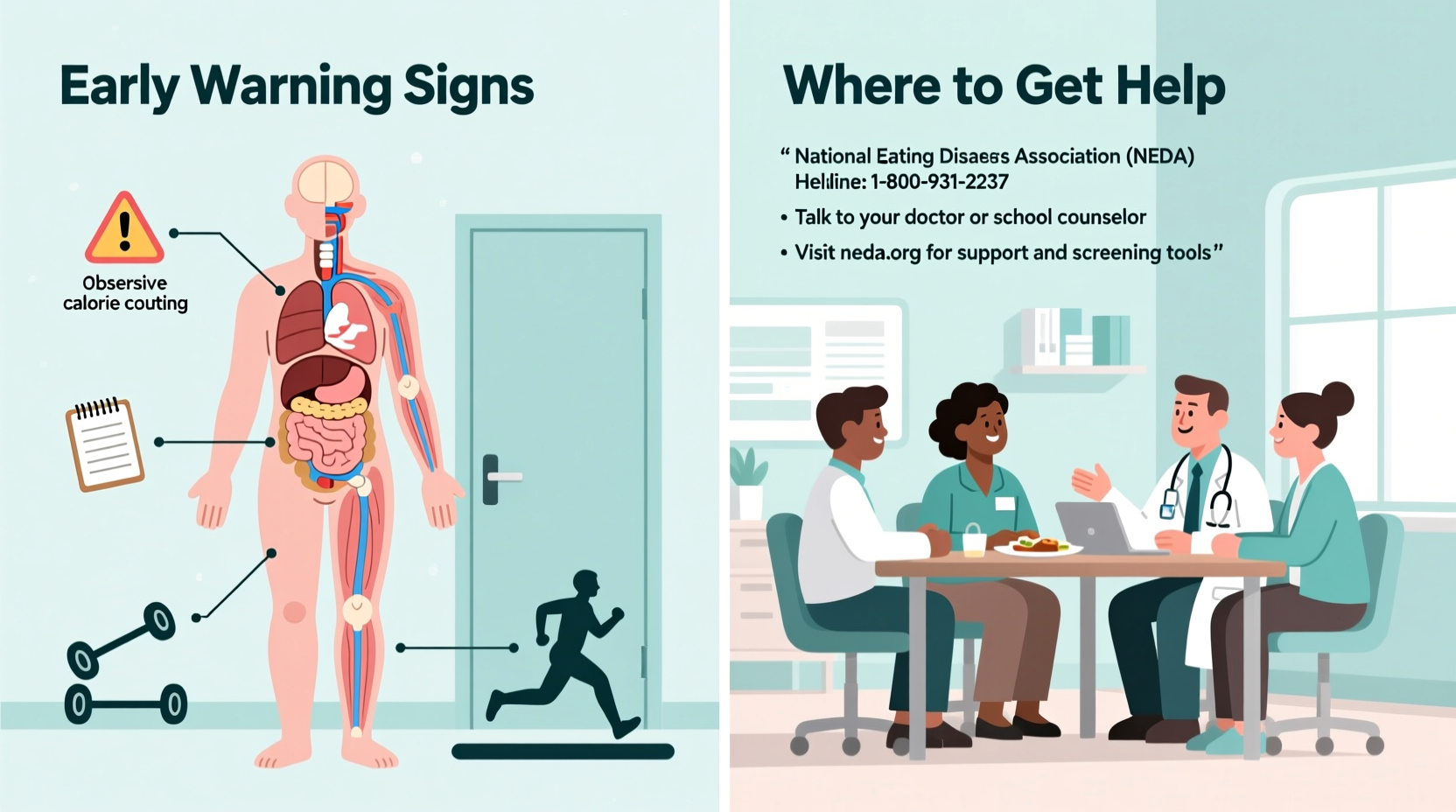

Early Warning Signs to Watch For

Spotting the initial symptoms of an eating disorder requires attentiveness to both visible behaviors and emotional shifts. These signs may appear gradually and can be mistaken for healthy dieting or stress-related habits. However, consistent patterns warrant concern.

- Dramatic weight changes: Rapid weight loss or gain without medical explanation.

- Preoccupation with food and calories: Obsessive calorie counting, rigid food rules, or avoidance of entire food groups.

- Withdrawal from social meals: Skipping family dinners, making excuses to eat alone, or avoiding restaurants.

- Frequent trips to the bathroom after eating: A potential sign of purging behavior.

- Excessive exercise: Compulsive workouts even when injured, fatigued, or in poor weather.

- Body image distortion: Persistent belief of being overweight despite being underweight.

- Wearing baggy clothes: Used to hide weight loss or discomfort with appearance.

- Mood swings or irritability around mealtimes: Anxiety, guilt, or agitation related to eating.

Do’s and Don’ts When Addressing Concerns

Approaching someone you suspect is struggling requires empathy and care. Missteps can increase shame or resistance. The table below outlines evidence-based communication strategies.

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Express concern using “I” statements: “I’ve noticed you seem stressed around meals.” | Comment on appearance: “You’ve lost so much weight—you look great!” |

| Listen without judgment; let them share at their pace. | Force them to eat or issue ultimatums. |

| Focus on feelings and behaviors, not food or weight. | Compare them to others or minimize their struggle. |

| Offer to help find professional support together. | Interrogate or demand immediate change. |

Real-Life Scenario: Emma’s Story

Emma, a 17-year-old high school student, began skipping lunch and exercising two hours daily after joining the track team. Her parents assumed she was simply dedicated to training. Over time, she stopped attending birthday parties, citing “not being hungry.” She became irritable, cold-intolerant, and developed brittle nails. When her teacher noticed her falling asleep in class and wearing multiple layers in warm weather, she contacted the school counselor. After a private conversation, Emma admitted she felt “out of control” and feared gaining weight. With her parents’ support, she entered outpatient therapy and nutritional counseling. Early identification prevented hospitalization and allowed her to return to school within months.

This case illustrates how symptoms can be masked as discipline or stress. It also highlights the importance of trained observers—teachers, coaches, healthcare providers—in initiating life-saving conversations.

Where and How to Get Help

Recovery from an eating disorder is possible, especially with timely, multidisciplinary care. The following steps outline a clear path to support:

- Consult a healthcare provider: A primary care physician can assess physical risks (e.g., electrolyte imbalances, heart irregularities) and refer to specialists.

- Seek a mental health evaluation: Licensed therapists trained in eating disorders use cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), or family-based treatment (FBT).

- Work with a registered dietitian: Nutritionists specializing in disordered eating help rebuild a healthy relationship with food.

- Consider treatment levels: Options range from outpatient programs to residential care, depending on severity.

- Involve support systems: Family therapy improves outcomes, especially for adolescents.

Trusted Resources and Hotlines

- National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) Helpline: Free, confidential support via chat, text, or phone. Available Monday–Thursday, 9 AM–9 PM EST. Visit nedo.org/help-support.

- ANAD (National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders): Offers free peer support groups and a referral network. Website: anad.org.

- Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation Eating Disorders Program: Provides low-cost treatment options and telehealth services.

- Crisis Text Line: Text “NEDA” to 741741 for immediate, anonymous crisis counseling.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can someone have an eating disorder even if they’re not underweight?

Absolutely. Binge eating disorder, bulimia, and OSFED often occur at average or higher weights. Weight is not a reliable indicator of illness. Internal suffering and harmful behaviors define these conditions, not size.

What if my loved one denies having a problem?

Denial is common due to fear, shame, or cognitive distortion caused by malnutrition. Continue expressing care without confrontation. Involve a professional who can conduct a neutral assessment. Sometimes, hearing concerns from a doctor or therapist carries more weight than from family.

Are eating disorders preventable?

While not always avoidable, risk can be reduced through promoting body diversity, discouraging diet culture, and fostering open communication about emotions. Schools and families play a vital role in building resilience before problems arise.

Conclusion: Take Action Before It’s Too Late

Recognizing the early signs of an eating disorder isn’t about suspicion—it’s about compassion. Whether you’re a parent, friend, teacher, or individual noticing changes in yourself, your awareness matters. These illnesses do not resolve on their own. Left untreated, they can lead to irreversible health damage or worse. But with early detection and proper care, recovery is not just possible—it’s probable.

If something feels off, trust your instincts. Reach out. Ask gentle questions. Connect with a professional. You don’t need to have all the answers—just the courage to begin the conversation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?