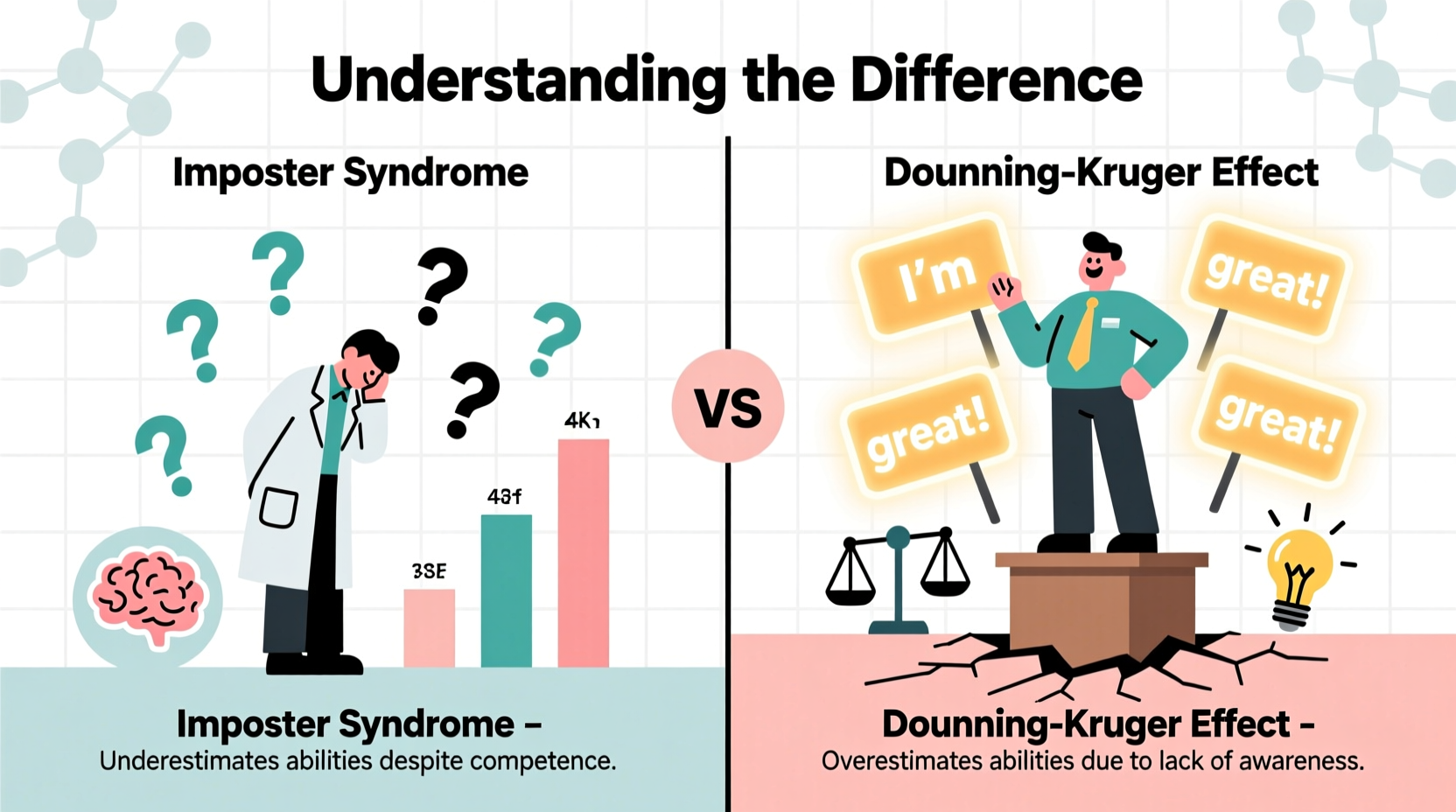

In professional and academic environments, two psychological phenomena frequently shape how people perceive their abilities: imposter syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger effect. While both influence self-assessment and performance, they operate in nearly opposite ways. One leads individuals to doubt their competence despite evidence of success; the other causes people to overestimate their skills despite clear deficiencies. Understanding the distinction is crucial for personal growth, leadership development, and fostering healthier team dynamics.

These cognitive biases don’t just affect isolated individuals—they ripple through workplaces, classrooms, and creative communities. Recognizing them allows you to support those struggling with self-doubt and challenge those who may lack awareness of their limitations. More importantly, it empowers you to reflect on your own patterns of thinking and build a more accurate, balanced self-perception.

Defining Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome refers to a persistent internal experience of feeling like a fraud, despite external evidence of competence and achievement. First identified by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes in 1978, it commonly affects high achievers who attribute their success to luck, timing, or deception rather than skill.

People experiencing imposter syndrome often fear being \"exposed\" as unqualified. They may downplay accomplishments, avoid challenges, or work excessively hard to compensate for perceived inadequacies. This pattern can lead to burnout, anxiety, and underutilization of talent—especially when individuals hesitate to apply for promotions or speak up in meetings.

The condition does not discriminate by profession or background. It appears among CEOs, scientists, artists, and students alike. What unites these individuals is not incompetence but a distorted self-view that undermines confidence.

Unpacking the Dunning-Kruger Effect

In contrast, the Dunning-Kruger effect describes a cognitive bias in which people with low ability at a task overestimate their competence. Named after psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who published their findings in 1999, this phenomenon stems from a lack of metacognitive skill—the ability to accurately assess one’s own performance.

Their research showed that individuals scoring in the lowest quartile on tests of logic, grammar, and humor significantly overestimated their results. For example, those in the 12th percentile believed they were performing in the 62nd. The irony lies in the fact that the very skills needed to succeed are the same ones required to recognize failure.

This effect isn’t limited to novices. It manifests in professionals who resist feedback, dismiss expertise, or make decisions without sufficient knowledge. In group settings, it can disrupt collaboration, especially when overconfident individuals dominate discussions despite offering flawed insights.

“We’re all ignorant, just about different things.” — Will Rogers, often cited by Dunning and Kruger to underscore the universality of unrecognized ignorance.

Key Differences Between the Two Phenomena

While both imposter syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger effect involve misjudgments of ability, they diverge fundamentally in direction, cause, and consequence. A side-by-side comparison clarifies these distinctions.

| Aspect | Imposter Syndrome | Dunning-Kruger Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Perception | Underestimation of ability | Overestimation of ability |

| Actual Performance | Often high | Typically low |

| Cause | Fear of exposure, perfectionism, attribution to external factors | Lack of metacognitive ability, absence of self-awareness |

| Emotional State | Anxiety, self-doubt, shame | Confidence, sometimes arrogance |

| Response to Feedback | Takes criticism personally, may fixate on flaws | May dismiss or ignore constructive input |

| Impact on Growth | Can drive over-preparation but also burnout | Hinders learning due to lack of recognition of gaps |

This table highlights a central irony: the most competent individuals are often the most self-critical, while the least skilled may be the most confident. This inversion has real implications for hiring, team management, and mentorship.

Real-World Example: The Workplace Meeting

Consider a product development meeting where five team members discuss a new feature rollout. One engineer, Maya, has consistently delivered reliable code and solved complex bugs. Yet during the discussion, she hesitates to propose her solution, prefacing it with, “This might be stupid, but…” She attributes past successes to teamwork and fears her idea isn’t innovative enough.

Meanwhile, Greg, a junior hire with limited experience in the system architecture, confidently advocates for a design approach he read about online. He interrupts others, insists his method is “obviously better,” and dismisses concerns about scalability. His proposal, while enthusiastic, lacks technical grounding.

In this scenario, Maya exhibits signs of imposter syndrome—high skill, low self-confidence. Greg demonstrates the Dunning-Kruger effect—low skill, high confidence. Without intervention, the team might overlook Maya’s valuable insight and adopt Greg’s flawed plan simply because he presented it with more certainty.

A skilled leader would validate Maya’s contribution publicly and ask Greg probing questions to gently expose knowledge gaps. This balance encourages humility in the overconfident and confidence in the underestimated.

Strategies to Overcome Each Challenge

Addressing these cognitive patterns requires intentional effort and environmental support. Below is a step-by-step guide tailored to each phenomenon.

For Managing Imposter Syndrome

- Track achievements objectively. Keep a “success journal” where you record completed tasks, positive feedback, and milestones. Review it weekly to counteract memory bias toward failure.

- Reframe self-talk. Replace thoughts like “I don’t belong here” with “I earned my place through consistent effort and results.”

- Seek mentorship. Talking with someone who has navigated similar doubts normalizes the experience and provides perspective.

- Accept imperfection. Understand that expertise includes making mistakes. Growth comes from iteration, not flawlessness.

- Share your feelings selectively. Opening up to trusted colleagues often reveals that others feel the same way, reducing isolation.

For Addressing the Dunning-Kruger Effect

- Encourage continuous learning. Promote a culture where asking questions is valued over pretending to know everything.

- Provide structured feedback. Use data-driven evaluations (e.g., peer reviews, test scores) to ground self-assessments in reality.

- Expose individuals to expert-level work. Seeing high-quality examples helps reveal the gap between novice and mastery.

- Teach metacognition. Train people to reflect on *how* they know what they know, including identifying assumptions and limitations.

- Foster intellectual humility. Reward curiosity and willingness to change one’s mind, not just assertiveness.

Actionable Checklist: Building Balanced Self-Awareness

Use this checklist to cultivate a more accurate self-perception and support others in doing the same:

- ✅ Regularly document your wins, no matter how small

- ✅ Compare your current skills to your past self, not only to experts

- ✅ Seek feedback from at least two trusted sources before making major decisions

- ✅ Reflect on failures without judgment—ask “What did I learn?” instead of “Why did I fail?”

- ✅ Challenge overconfidence in meetings by asking, “What could go wrong with this approach?”

- ✅ Normalize saying “I don’t know” and follow it with “But I’ll find out.”

- ✅ Encourage team members to present ideas with supporting data, not just enthusiasm

“Knowing what you don't know is more important than knowing facts. It's the foundation of wisdom.” — Nicholas Taleb, author of *The Black Swan*

FAQ: Common Questions Answered

Can someone experience both imposter syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger effect?

Yes—but usually in different areas. A person might suffer from imposter syndrome in their professional role while displaying Dunning-Kruger tendencies in a hobby or unrelated skill. The brain doesn’t apply self-assessment uniformly across domains. Context, experience level, and emotional investment all influence which bias emerges.

Is the Dunning-Kruger effect just arrogance?

Not necessarily. While it can manifest as overconfidence, the core issue is a lack of awareness, not ego. Many affected individuals aren’t trying to deceive others; they genuinely believe they understand a topic. Arrogance implies willful superiority, whereas the Dunning-Kruger effect stems from cognitive limitation.

Does imposter syndrome ever go away?

It often diminishes with time, therapy, and repeated success—but rarely disappears completely. Even seasoned professionals like Neil Gaiman and Michelle Obama have admitted to feeling like imposters. The goal isn’t elimination but management: learning to act despite doubt, not waiting for it to vanish.

Conclusion: Toward Greater Self-Awareness

Imposter syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger effect represent two sides of a universal human struggle: accurately seeing ourselves. One pulls us into unwarranted self-doubt; the other propels us into unfounded confidence. Neither serves us well in isolation.

The path forward isn’t about erasing these tendencies—after all, they’re rooted in normal cognitive processes—but about cultivating awareness, compassion, and balance. By recognizing when we’re minimizing our strengths or overlooking our blind spots, we create space for authentic growth.

Leaders, educators, and individuals alike benefit from fostering environments where vulnerability is safe, feedback is constructive, and learning never ends. Start today: reflect honestly on your last project, celebrate progress without inflation, and remain open to the possibility that you’re either better—or less skilled—than you think.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?