Inhalation, often taken for granted as a simple act of breathing, is actually a complex and precisely coordinated physiological event. While it may feel effortless, especially during rest, inhalation is fundamentally an active process—meaning it requires energy and deliberate muscular effort. Unlike exhalation, which is typically passive at rest, drawing air into the lungs involves multiple systems working in concert to create the necessary pressure gradients. Understanding why inhalation is active provides deeper insight into respiratory physiology and highlights how our bodies maintain life-sustaining gas exchange.

The Mechanics of Inhalation: How It Works

At its core, inhalation depends on changes in thoracic cavity volume, which alter air pressure inside the lungs relative to the atmosphere. According to Boyle’s Law, when volume increases, pressure decreases. This principle drives airflow: when lung pressure drops below atmospheric pressure, air rushes in.

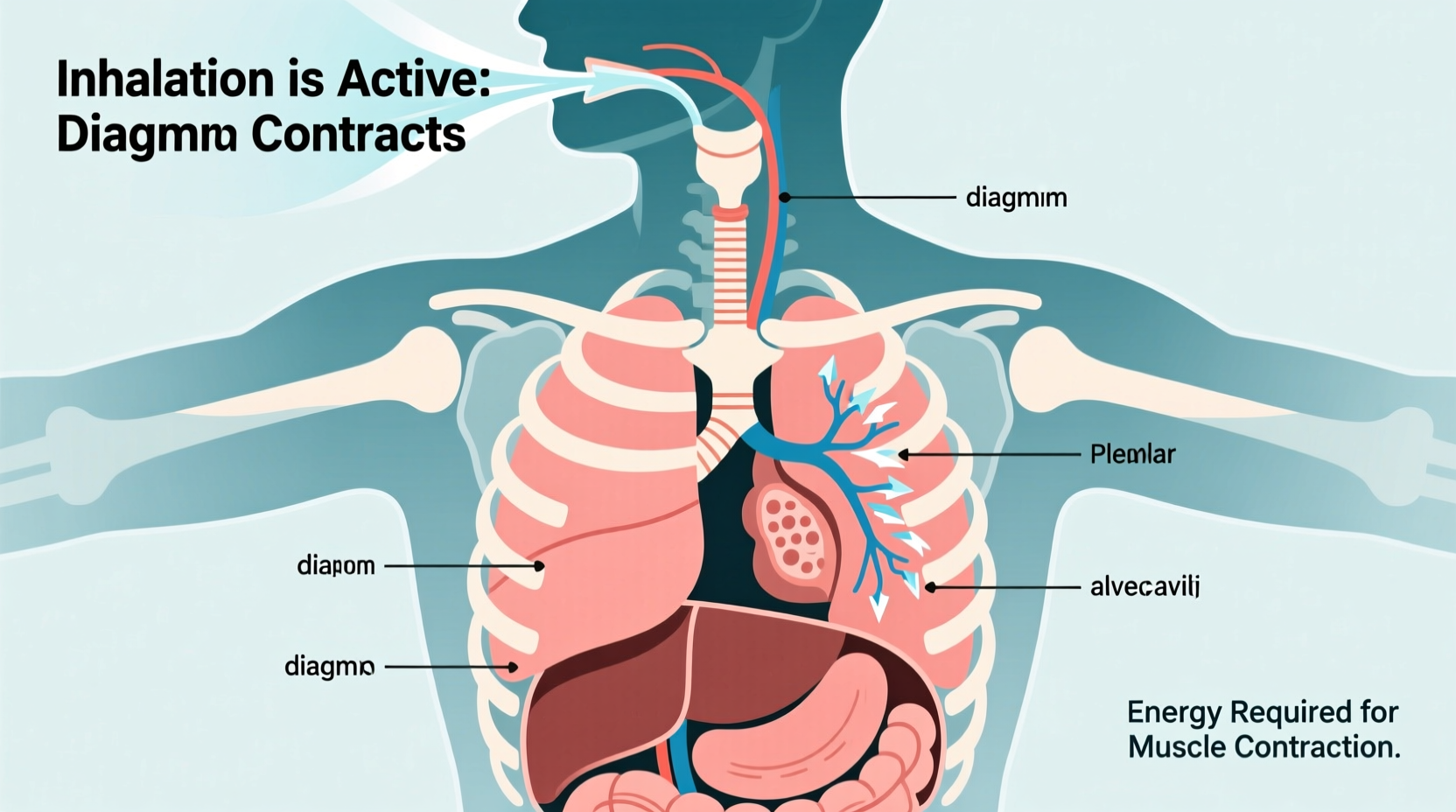

This volume change is achieved primarily through the contraction of two key muscles: the diaphragm and the external intercostal muscles. The diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscle beneath the lungs, flattens and moves downward when it contracts. Simultaneously, the external intercostal muscles between the ribs lift the rib cage upward and outward. Together, these actions expand the thoracic cavity in three dimensions—vertically, anteroposteriorly, and laterally.

The expansion creates negative intrapleural pressure (the pressure within the pleural cavity surrounding the lungs), causing the lungs to stretch and fill with air. Because this entire sequence relies on muscular contractions powered by ATP, inhalation qualifies as an active biological process.

Muscle Involvement in Active Inhalation

The primary muscles responsible for inhalation are not just accessories—they are essential drivers of the process. Their activation is controlled by the phrenic nerve (for the diaphragm) and intercostal nerves, both originating from the brainstem's respiratory centers.

- Diaphragm: Accounts for about 75% of air movement during quiet breathing. Its contraction increases vertical dimension of the thorax.

- External Intercostals: Elevate the ribs, increasing the front-to-back and side-to-side dimensions of the chest cavity.

- Accessory Muscles: Used during forced or labored breathing (e.g., exercise or asthma). These include the sternocleidomastoid, scalene, and pectoralis minor muscles, which further elevate the rib cage.

Each contraction consumes energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), confirming that work is being done. This metabolic cost underscores the classification of inhalation as active. Even during rest, the nervous system continuously signals these muscles to contract rhythmically—approximately 12–20 times per minute in adults.

“Breathing isn’t passive because the body must constantly generate force to overcome elastic recoil and airway resistance.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Pulmonary Physiologist, Johns Hopkins Medicine

Why Exhalation Is Usually Passive—And When It Isn’t

To better appreciate why inhalation is active, it helps to contrast it with exhalation. At rest, exhalation occurs without muscular effort. Once the diaphragm and intercostals relax, the natural elasticity of the lungs and chest wall causes them to recoil inward, decreasing thoracic volume and increasing internal pressure. Air flows out as a result—no additional energy required.

However, during heavy exercise, coughing, or respiratory conditions like COPD, exhalation becomes active too. Abdominal muscles and internal intercostals contract to forcefully push air out, reducing lung volume beyond normal elastic limits. But under normal conditions, only inhalation demands consistent energy expenditure.

| Process | Muscle Activity | Energy Required? | Pressure Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhalation (quiet) | Diaphragm + External intercostals contract | Yes – Active | Lung pressure < Atmosphere |

| Exhalation (quiet) | Muscles relax; elastic recoil only | No – Passive | Lung pressure > Atmosphere |

| Inhalation (forced) | Accessory muscles engaged | Yes – Highly Active | Greater negative pressure |

| Exhalation (forced) | Abdominals + Internal intercostals contract | Yes – Active | High positive pressure |

Step-by-Step: The Physiological Sequence of Inhalation

Understanding the precise order of events reveals the sophistication behind what seems like a simple breath. Here’s how active inhalation unfolds in real time:

- Neural Signal Initiation: The medulla oblongata and pons in the brainstem generate rhythmic impulses sent via spinal nerves.

- Diaphragm Activation: Phrenic nerves stimulate the diaphragm to contract, moving it downward by 1–2 cm.

- Rib Cage Expansion: External intercostal muscles contract, lifting the ribs and expanding the chest laterally and anteriorly.

- Thoracic Volume Increase: The combined effect increases the volume of the thoracic cavity.

- Pressure Drop: Increased volume leads to decreased intra-alveolar pressure (typically dropping to about -1 mmHg relative to atmosphere).

- Air Inflow: Air flows down the pressure gradient through the nose/mouth, trachea, bronchi, and into alveoli.

- Gas Exchange Prepares: Oxygen diffuses across alveolar membranes into capillaries; CO₂ prepares to exit on exhalation.

This sequence repeats automatically but can be overridden voluntarily—such as when holding your breath or taking deep breaths during meditation.

Common Misconceptions About Breathing

Many people assume all breathing is passive, especially since we do it unconsciously. However, even unconscious breathing requires constant neural and muscular activity. Other misconceptions include:

- \"Breathing uses no energy.\" False—each breath consumes ATP, particularly during increased demand.

- \"The lungs pump air themselves.\" Lungs are passive structures; they rely entirely on surrounding muscles for inflation.

- \"Deep breathing is unnatural.\" On the contrary, diaphragmatic breathing is optimal and reduces strain on accessory muscles.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is inhalation always active?

Yes, under all physiological conditions, inhalation requires muscular contraction and therefore remains an active process. Even during sleep or sedation, the diaphragm continues contracting via automatic neural control.

Why doesn't inhalation feel tiring if it's active?

Because the muscles involved—especially the diaphragm—are highly efficient and designed for endurance. At rest, the workload is minimal. Only during intense physical activity or illness does the effort become noticeable.

Can you breathe without using your diaphragm?

Temporarily, yes—using accessory muscles in the neck and chest. But long-term reliance on these muscles (as seen in chronic lung disease) is inefficient and fatiguing. The diaphragm remains the most effective inhalation muscle.

Conclusion: Embracing the Effort Behind Every Breath

Inhalation is far more than a reflex—it is a dynamic, energy-dependent process vital to sustaining life. Recognizing it as active shifts our understanding of respiration from passive survival to active maintenance. From the silent rise of the diaphragm at rest to the powerful engagement of accessory muscles during exertion, each breath reflects a finely tuned system working tirelessly behind the scenes.

By appreciating the physiology of inhalation, we gain respect for the complexity of our own bodies—and motivation to support respiratory health through good posture, regular exercise, and mindful breathing practices. Your next breath might feel automatic, but now you know: it’s the result of precise, purposeful effort.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?