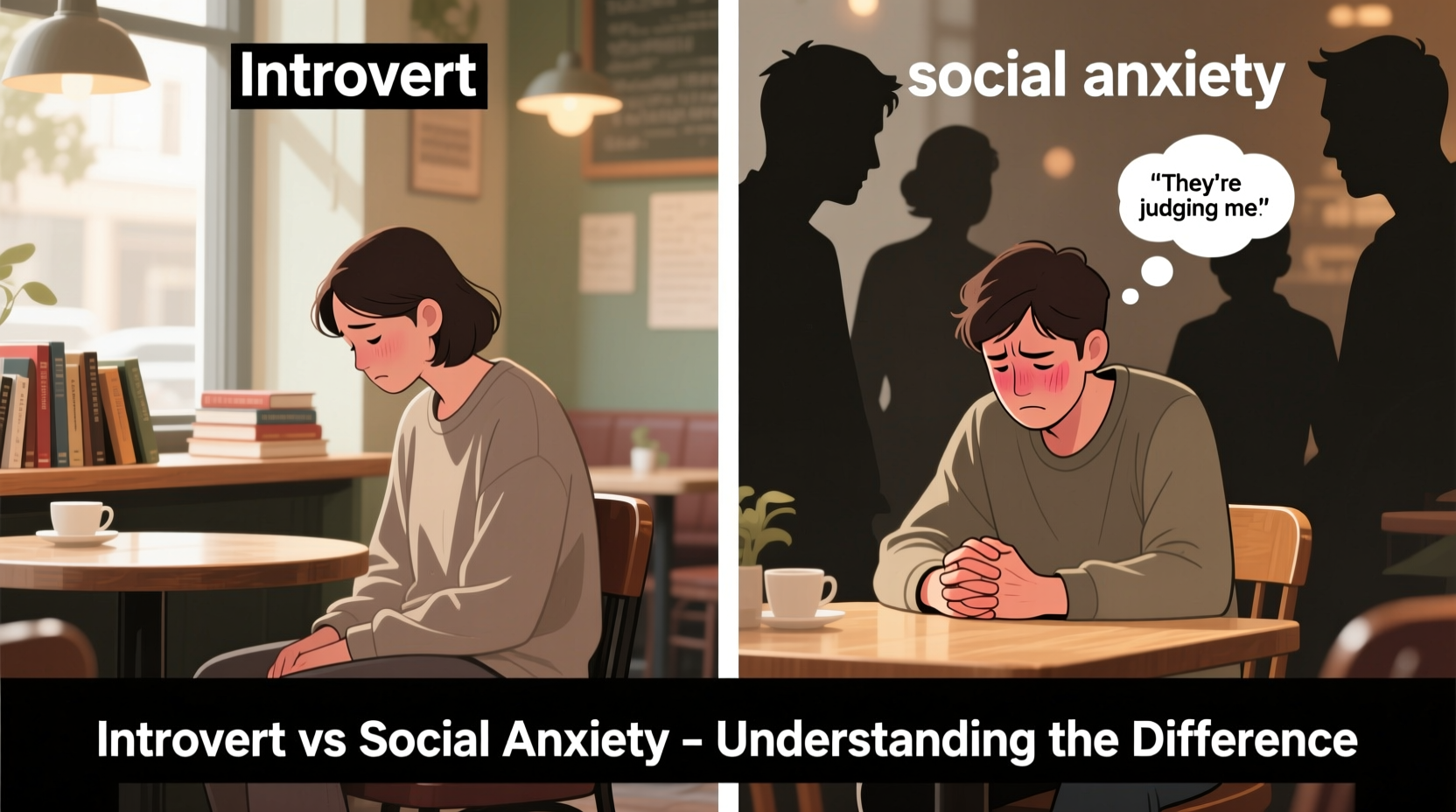

Many people use the terms “introvert” and “socially anxious” interchangeably, but they describe fundamentally different experiences. One is a personality trait; the other is a mental health condition. Confusing the two can lead to misjudgment, unnecessary self-criticism, or missed opportunities for growth. Understanding the distinction empowers individuals to approach social challenges with clarity, compassion, and effective strategies.

Introversion is not a flaw or something to be fixed. It’s a natural preference for quieter, more reflective environments. Social anxiety, on the other hand, involves intense fear of judgment that can interfere with daily functioning. Recognizing where you fall on this spectrum helps you build authentic connections without compromising your well-being.

What Is Introversion? A Preference, Not a Problem

Introversion describes how a person gains energy and processes stimulation. Introverts typically feel most at ease in low-stimulation environments and often prefer one-on-one conversations or small gatherings over large parties. They may take time to reflect before speaking and value depth over breadth in relationships.

This trait is part of the broader personality spectrum identified in models like the Big Five. Carl Jung first introduced the concept, emphasizing that introversion isn’t about shyness—it’s about internal processing and energy management. An introvert might enjoy socializing deeply but will likely need solitude afterward to recharge.

Introverts often excel in roles requiring focus, listening, and thoughtful decision-making. Their tendency to observe before acting can make them insightful partners, friends, and leaders. The challenge arises when society equates outgoing behavior with competence or likability, pressuring introverts to perform extroversion—a draining and unsustainable act.

Social Anxiety: When Fear Overrides Function

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), recognized in the DSM-5, goes beyond occasional nervousness. It’s characterized by persistent fear of social situations where scrutiny may occur—speaking up in meetings, eating in public, attending parties, or even making eye contact. The fear stems from anticipating embarrassment, rejection, or negative evaluation.

Unlike situational nerves, social anxiety causes significant distress and avoidance behaviors. People with SAD may turn down job opportunities, skip family events, or isolate themselves despite wanting connection. Physical symptoms include trembling, sweating, rapid heartbeat, and nausea. These reactions are automatic, rooted in the body’s threat-detection system.

“Social anxiety isn’t just shyness—it’s a chronic fear of being judged that can impair quality of life. Treatment works, but recognition is the first step.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Clinical Psychologist

The key distinction lies in desire versus dread. Many socially anxious individuals crave meaningful interaction but are held back by overwhelming fear. In contrast, introverts may choose less social engagement because it aligns with their energy needs, not because they’re afraid.

Comparing Introversion and Social Anxiety: Key Differences

To clarify the overlap and distinctions, consider the following comparison:

| Aspect | Introversion | Social Anxiety |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Personality trait | Mental health condition |

| Motivation | Preference for quiet, reflection | Fear of judgment or humiliation |

| Energy Source | Recharged by solitude | Drained by social exposure due to stress |

| Post-Social Feelings | Tired but satisfied if meaningful | Relieved to escape, possibly ruminating on perceived mistakes |

| Desire for Connection | Present, but selective | Strong, but fear blocks access |

| Treatment Needed? | No—self-awareness suffices | Often yes—therapy or medication helpful |

This table underscores that while both may result in limited social participation, the underlying reasons differ significantly. Mislabeling social anxiety as mere introversion can delay help-seeking. Conversely, pathologizing introversion creates unnecessary pressure to change a core aspect of identity.

Real-Life Example: Maya’s Journey

Maya, a 29-year-old graphic designer, always avoided office happy hours and rarely spoke in team meetings. Coworkers assumed she was unfriendly or disengaged. Internally, she wrestled with conflicting feelings: she wanted to connect but feared saying the wrong thing. Her heart would race during presentations, and she’d replay conversations for hours, convinced she’d sounded awkward.

After months of sleepless nights and declining invitations, she consulted a therapist. Through assessment, it became clear: Maya wasn’t just introverted—she met criteria for social anxiety disorder. Her discomfort wasn’t about energy management; it was driven by catastrophic thinking (“They’ll think I’m stupid”) and hypervigilance to social cues.

With cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Maya learned to identify distorted thoughts and gradually face feared situations. She started by asking one question per meeting, then progressed to leading short check-ins. Over six months, her confidence grew. Importantly, she also honored her introverted side by scheduling recovery time after social exertion.

Today, Maya still prefers small groups and values deep conversations. But now, she chooses her level of engagement—not out of fear, but intention.

Practical Strategies for Healthier Socializing

Whether you’re introverted, socially anxious, or somewhere in between, these steps can support healthier social interactions.

1. Self-Assessment: Know Your Triggers

Keep a brief journal for one week. Note each social interaction, your energy level before and after, and any physical or emotional discomfort. Ask yourself: Is my hesitation due to fatigue or fear? Am I avoiding because I’m overwhelmed, or because I’m afraid of being judged?

2. Reframe Social Goals

Instead of aiming to “be more outgoing,” set realistic objectives: “I’ll introduce myself to one new person,” or “I’ll stay at the event for 45 minutes.” Small wins build momentum without burnout.

3. Practice Exposure Gradually

If anxiety is present, use graded exposure. Start with lower-pressure situations—like ordering coffee and making brief eye contact—then work up to group discussions. Track progress to see improvement over time.

4. Leverage Introverted Strengths

Use active listening, empathy, and thoughtfulness as social tools. People appreciate genuine attention. Prepare conversation starters in advance if spontaneity feels challenging.

5. Create Recovery Rituals

After socializing, allow transition time. Read, walk in nature, or listen to calming music. This honors your energy cycle and prevents resentment toward social demands.

“Confidence isn’t the absence of fear—it’s acting in spite of it. And for introverts, depth often trumps volume in building real connection.” — Marcus Reed, Social Skills Coach

Action Checklist: Building Better Social Habits

- ✅ Identify whether your social hesitation stems from energy needs (introversion) or fear (anxiety)

- ✅ Journal social experiences for one week to detect patterns

- ✅ Set one small, achievable social goal for the next seven days

- ✅ Schedule downtime before and after social events

- ✅ Practice one exposure exercise (e.g., greeting a neighbor)

- ✅ Seek professional support if fear regularly disrupts your life

- ✅ Celebrate effort, not just outcomes

Frequently Asked Questions

Can someone be both introverted and have social anxiety?

Yes, absolutely. Many people experience both. An introvert may naturally prefer solitude, but if they also fear judgment or avoid socializing due to shame or panic, social anxiety may be present. The two can coexist and require different strategies—honoring energy needs while actively reducing fear-based avoidance.

Is social anxiety just extreme shyness?

No. While shyness may involve temporary discomfort, social anxiety is more persistent and impairing. It often begins in adolescence and can lead to long-term avoidance, impacting education, career, and relationships. Unlike shyness, it responds well to evidence-based treatments like CBT and sometimes medication.

Do introverts need therapy to improve social skills?

Not necessarily. Introversion doesn’t require treatment. However, therapy can help introverts develop communication tools, assert boundaries, or navigate extrovert-dominated environments. It becomes essential only if there’s distress, avoidance, or anxiety interfering with desired goals.

Conclusion: Embrace Clarity, Build Confidence

Understanding the difference between introversion and social anxiety is not just academic—it’s liberating. It allows you to stop blaming yourself for being “too quiet” when you’re simply recharging, and to take action when fear is holding you back from what you truly want.

Your social style isn’t a defect. Whether you thrive in stillness or struggle with fear, awareness is the foundation of change. Use this knowledge to advocate for your needs, seek support when necessary, and engage with others on your own terms.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?