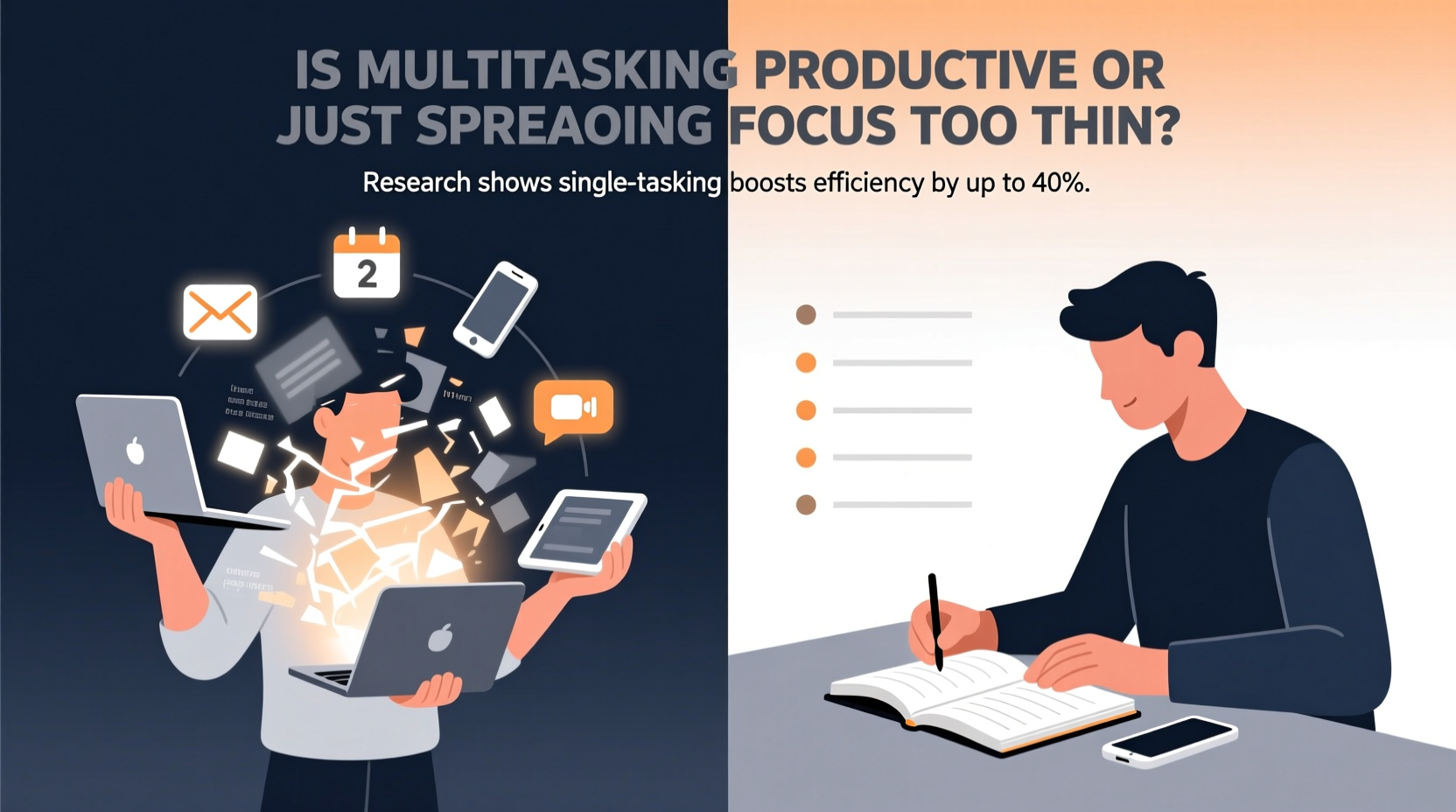

In an age where speed is praised and busyness mistaken for efficiency, multitasking has become a badge of honor. Many professionals boast about juggling emails during meetings, texting while writing reports, or answering calls while reviewing spreadsheets. But beneath the surface of this perceived productivity lies a growing body of scientific evidence suggesting that multitasking may not only be ineffective—it could actually be damaging to performance, focus, and mental well-being.

The human brain isn’t designed to handle multiple complex tasks simultaneously. Instead, what we call “multitasking” is more accurately described as rapid task-switching. Each time attention shifts from one activity to another, there’s a cognitive cost—milliseconds at first, but they accumulate into significant losses over a workday. The result? Lower quality output, increased errors, and higher stress levels. So, is multitasking truly productive, or are we simply spreading our focus too thin?

The Myth of Multitasking: What Science Says

Neuroscience has consistently challenged the idea that humans can effectively perform two cognitively demanding tasks at once. Dr. Earl Miller, a neuroscientist at MIT, explains that the brain doesn’t truly multitask—it toggles between tasks so quickly that it gives the illusion of simultaneity. This switching comes with a price known as “switching cost,” which refers to the time and accuracy lost each time the brain shifts gears.

Studies conducted at Stanford University found that heavy multitaskers were actually worse at filtering out irrelevant information, organizing their thoughts, and completing tasks efficiently compared to those who focused on one thing at a time. Paradoxically, people who believed they were good at multitasking performed the poorest in controlled experiments.

One key reason is cognitive load. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making and attention control, becomes overloaded when managing competing demands. This overload reduces working memory capacity and impairs judgment. For example, trying to write a proposal while responding to Slack messages leads to fragmented thinking, weaker arguments, and more revisions later.

“Multitasking is a myth. The brain can only deeply engage with one complex task at a time. Everything else is distraction disguised as productivity.” — Dr. Gloria Mark, Professor of Informatics, UC Irvine

The Hidden Costs of Constant Task-Switching

While the intention behind multitasking is often to get more done faster, the reality is quite different. Here are some of the most significant hidden costs:

- Reduced productivity: Research from the American Psychological Association shows that task-switching can reduce productivity by up to 40%, especially when tasks require different rules or thought processes.

- Increased error rates: A study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology found that interruptions—even brief ones—doubled the number of errors made in complex tasks like programming or data analysis.

- Higher stress levels: Constant context-switching triggers the release of cortisol and adrenaline, contributing to chronic stress, fatigue, and burnout.

- Poorer learning and retention: When attention is divided, the brain struggles to encode information into long-term memory, making training, reading, or skill acquisition less effective.

- Diminished creativity: Deep creative thinking requires uninterrupted focus. Multitasking fragments the mind’s ability to make novel connections or explore ideas fully.

When Multitasking Works (and When It Doesn’t)

Not all multitasking is inherently bad. The distinction lies in the nature of the tasks involved. Simple, automatic, or low-cognitive-load activities can sometimes be paired without major drawbacks.

| Task Type | Suitable for Multitasking? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Routine physical + passive listening | Yes | Walking on a treadmill while listening to a podcast |

| Manual labor + music | Yes | Folding laundry while playing background music |

| Two high-focus cognitive tasks | No | Writing a report while analyzing financial data |

| Communication + complex problem-solving | No | Answering emails while debugging code |

| Learning something new + distractions | No | Studying a language while checking social media |

The rule of thumb: if both tasks demand conscious attention, multitasking will impair performance. However, pairing a habitual task with a passive or low-effort one can be efficient and even enjoyable.

A Real-World Example: Sarah’s Workday Transformation

Sarah, a marketing manager at a mid-sized tech firm, used to pride herself on her ability to “handle everything at once.” Her typical morning included checking emails during team stand-ups, drafting campaign copy while on Zoom calls, and scrolling through Slack while preparing presentations. She felt busy all day but often stayed late to fix mistakes or redo incomplete work.

After attending a workshop on focused work, she decided to experiment. For one week, she blocked 90-minute sessions for deep work, silenced all notifications, and scheduled specific times for email and messaging. Meetings were attended without laptops unless absolutely necessary.

The results were striking. She completed projects 30% faster, reduced errors in deliverables, and reported feeling less mentally drained. Her team noticed improved clarity in her communications and more thoughtful contributions in discussions. By doing less at once, Sarah achieved more overall.

How to Shift from Multitasking to Mindful Focus

Breaking the multitasking habit requires intentional changes in behavior and environment. Below is a step-by-step guide to cultivating deeper focus:

- Track your distractions: For two days, log every interruption—notifications, internal urges, colleague requests. Identify patterns.

- Define focus blocks: Schedule 60–90 minute windows for single-tasking. Use calendar appointments to protect this time.

- Turn off digital noise: Disable non-urgent notifications on devices. Use tools like “Do Not Disturb” or app blockers.

- Batch communication: Check emails and messages only at set intervals (e.g., 10 a.m., 1 p.m., 4 p.m.). Train others to expect delayed responses.

- Create a distraction-free zone: Keep your workspace clean, close unnecessary browser tabs, and use headphones as a visual cue.

- Practice monotasking: Start with small wins—read an article without checking your phone, or write a paragraph without pausing to edit.

- Reflect daily: At the end of each day, ask: What was my most valuable contribution? Was I truly focused when I did it?

Actionable Checklist: Build a Focused Workflow

Use this checklist weekly to reinforce focused work habits:

- ☐ Plan the top 3 priorities for the day each morning

- ☐ Schedule at least two 90-minute focus blocks

- ☐ Silence phone and desktop notifications during deep work

- ☐ Close all unrelated browser tabs and apps before starting

- ☐ Communicate availability to colleagues (e.g., “In focus mode until 11 a.m.”)

- ☐ Review completed tasks without self-judgment—focus on effort, not perfection

- ☐ Reflect: Did I feel mentally scattered or centered today?

Frequently Asked Questions

Isn’t multitasking necessary in fast-paced jobs?

While some roles require quick pivoting, true multitasking isn’t sustainable under pressure. High performers in fast environments use structured task management—prioritizing, delegating, and focusing on one critical item at a time—rather than attempting simultaneous execution. Agility comes from clarity, not chaos.

Can training improve multitasking ability?

Limited evidence suggests that certain types of dual-task training (e.g., in aviation or surgery) can improve coordination between specific tasks. However, for general knowledge work, no training can overcome the brain’s biological limits. The better investment is in attention control, mindfulness, and workflow design.

What about listening to music while working?

This depends on the task and the music. Instrumental or ambient tracks with no lyrics can enhance focus for repetitive or creative tasks. However, lyrical music or high-tempo genres may interfere with reading, writing, or analytical thinking. Experiment to find your personal balance.

Conclusion: Reclaim Your Attention, Reclaim Your Productivity

Multitasking isn’t the hallmark of a productive professional—it’s a trap disguised as efficiency. The modern workplace rewards the appearance of busyness, but real progress happens in moments of undivided attention. By understanding the cognitive costs of task-switching and adopting practices that support deep focus, you can produce higher-quality work, reduce stress, and regain control over your time.

Productivity isn’t about doing more things at once. It’s about doing the right thing with full presence. Start small: protect one hour a day for single-tasking. Notice the difference in your output and mental clarity. Over time, these focused intervals compound into meaningful achievements that no amount of frantic multitasking ever could.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?