Plastic water bottles are convenient, portable, and widely used across the globe. Many people, aiming to reduce waste or save money, refill their single-use bottles multiple times. But is this practice truly safe? Over the past two decades, researchers have examined the health implications of repeatedly using disposable plastic bottles. The findings reveal a complex picture involving chemical leaching, microbial contamination, and physical degradation of plastic. While occasional reuse may pose minimal risk, long-term habits could expose individuals to unseen dangers.

The core issue lies in the design intent: most plastic water bottles are engineered for one-time use. Their materials, while effective for short-term storage, were not designed to withstand repeated washing, exposure to heat, or prolonged contact with liquids. As these bottles age and degrade, they can release substances into the water—some of which have raised concerns among toxicologists and public health experts.

Understanding Plastic Types and Recycling Codes

Not all plastics are created equal. The resin identification code—those numbers inside the recycling triangle on the bottom of bottles—provides critical information about the material used. These codes range from 1 to 7, each representing a different type of plastic polymer. When it comes to reusing water bottles, the most common type is #1: PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate).

PET is lightweight, clear, and ideal for single-use beverage containers. However, its structural integrity begins to break down after repeated use, especially when exposed to heat or abrasive cleaning methods. Studies show that PET bottles can develop microscopic cracks and surface irregularities over time, creating ideal environments for bacteria to colonize.

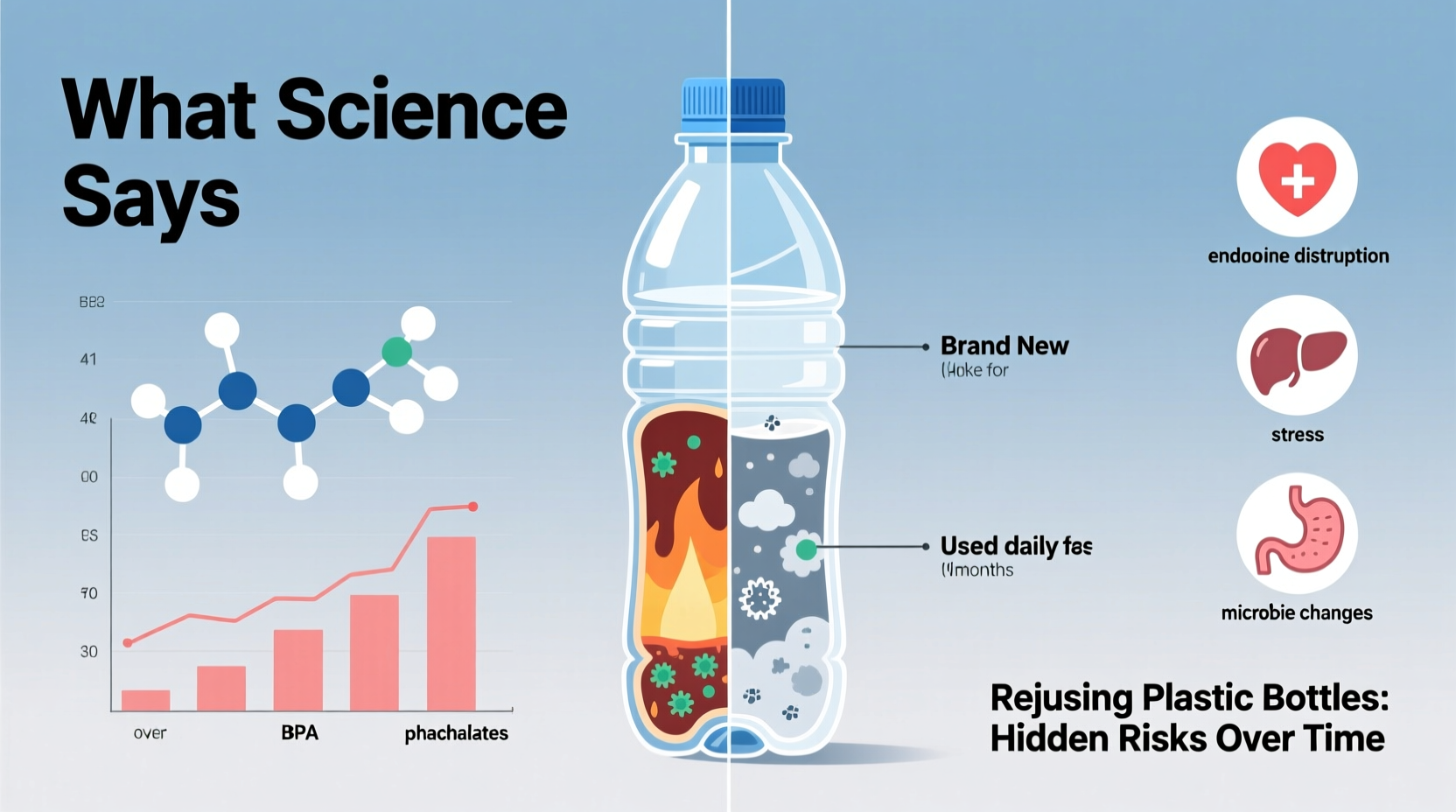

Other plastics like #2 (HDPE), #4 (LDPE), and #5 (PP) are more chemically stable and often labeled as “reusable,” but they are rarely used in standard disposable water bottles. Bottles marked with #3 (PVC), #6 (PS), and #7 (other, including polycarbonate) may contain additives like phthalates or bisphenols (e.g., BPA), which have been linked to endocrine disruption.

“PET bottles are not designed for repeated use. Over time, wear and environmental stress can compromise both the physical and chemical safety of the container.” — Dr. Laura Chen, Environmental Toxicologist, University of California

Chemical Leaching: What Happens Inside Reused Bottles?

One of the primary concerns with reusing plastic bottles is the potential for chemicals to leach into the water. This process accelerates under certain conditions, particularly heat and mechanical stress. While PET does not contain BPA, it may still release other compounds such as antimony and acetaldehyde.

- Antimony: A metalloid used as a catalyst in PET production. Long-term exposure to high levels can cause gastrointestinal issues and respiratory problems. Research published in *Environmental Health Perspectives* found that antimony levels in bottled water increased significantly after prolonged storage in warm environments.

- Acetaldehyde: A byproduct of PET degradation. It can impart a sweet, fruity odor to water and, in high concentrations, may irritate the eyes and respiratory tract.

- Microplastics: Tiny plastic particles shed from the bottle’s interior due to abrasion from brushing or freezing. A 2024 study from Columbia University detected an average of 240 microplastic fragments per liter in reused PET bottles after three weeks of daily use.

Temperature plays a crucial role. Leaving a plastic bottle in a hot car or near a heat source can increase the rate of chemical migration. One experiment demonstrated that storing a PET bottle at 60°C (140°F) for five days led to a 300% increase in antimony concentration compared to room temperature storage.

Bacterial Contamination: The Hidden Threat in Reused Bottles

While chemical concerns dominate headlines, microbial contamination poses a more immediate and measurable risk. A reused plastic bottle, especially one handled frequently and filled with sugary drinks or saliva-contaminated water, becomes a breeding ground for bacteria.

A 2018 study conducted by the University of Calgary tested 70 reusable plastic bottles used by children in elementary schools. Nearly 25% showed coliform bacteria, and 9% contained detectable levels of E. coli—indicating fecal contamination. The primary sources? Poor hand hygiene and inadequate cleaning.

The narrow necks of disposable bottles make thorough cleaning difficult. Sponges and brushes often cannot reach the bottom, leaving biofilm—a slimy layer of microbes—intact. Once established, biofilm resists regular rinsing and promotes persistent contamination.

| Risk Factor | Impact on Bottle Safety |

|---|---|

| Warm Environment | Accelerates bacterial growth and chemical leaching |

| Frequent Mouth Contact | Introduces saliva and oral bacteria into the bottle |

| Inadequate Cleaning | Allows biofilm formation and microbial buildup |

| Scratches or Cracks | Provide hiding spots for bacteria and increase surface area for leaching |

Real-World Example: The Office Worker’s Habit

Consider Mark, a 34-year-old office worker who refills his disposable 500ml PET water bottle every day. He keeps it on his desk, refills it from the cooler, and occasionally washes it with soap and tap water. After six months, the bottle appears cloudy and has a faint odor. Unaware of the risks, Mark continues using it.

Over time, microscopic scratches from daily use trap bacteria. The repeated exposure to indoor lighting and ambient warmth encourages microbial proliferation. Laboratory testing of a similar bottle revealed colonies of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—organisms capable of causing skin infections and gastrointestinal discomfort, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

This case illustrates how seemingly harmless behavior, without proper hygiene and awareness, can lead to chronic exposure to contaminants. Switching to a durable, wide-mouth reusable bottle would significantly reduce these risks.

Safer Alternatives and Best Practices

For those committed to sustainability and health, transitioning to safer, long-term reusable options is the best solution. Materials like stainless steel, glass, and BPA-free Tritan plastic are engineered for repeated use and resist both chemical degradation and bacterial colonization.

When choosing a reusable bottle, consider the following features:

- Wide mouth for easy cleaning

- Dishwasher-safe construction

- No lining or coatings that may degrade

- Materials certified as food-grade and non-toxic

“Switching to a high-quality reusable bottle isn’t just better for the environment—it reduces your exposure to microplastics and harmful microbes.” — Dr. Naomi Patel, Public Health Microbiologist

Step-by-Step Guide to Safe Hydration Habits

- Assess your current bottle: If it’s a #1 PET bottle, recognize it’s meant for single use. Avoid refilling it more than once or twice.

- Inspect for damage: Discard any bottle with cracks, cloudiness, or persistent odor.

- Clean thoroughly: Use hot soapy water and a bottle brush daily. For deeper sanitization, soak in a vinegar-water solution (1:3 ratio) weekly.

- Choose a durable alternative: Invest in a stainless steel or glass bottle with a protective sleeve.

- Replace regularly: Even reusable bottles should be replaced every 1–2 years or if damaged.

Do’s and Don’ts of Reusing Plastic Bottles

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Use bottles labeled as reusable (e.g., Tritan, stainless steel) | Refill single-use PET (#1) bottles more than a few times |

| Wash bottles daily with hot, soapy water | Put disposable plastic bottles in the dishwasher (heat warps them) |

| Store bottles in cool, dry places | Leave bottles in hot cars or direct sunlight |

| Replace bottles showing signs of wear | Use scratched or cracked bottles, even if cleaned |

| Use a bottle brush for narrow-neck containers | Share bottles with others to prevent germ transmission |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get cancer from reusing plastic water bottles?

There is no conclusive scientific evidence linking the reuse of PET bottles directly to cancer. While some studies have detected trace amounts of carcinogenic substances under extreme conditions (like high heat), the levels are generally below safety thresholds set by health agencies. However, minimizing exposure to degraded plastics is a prudent precaution.

Are \"BPA-free\" labels enough to ensure safety?

Not necessarily. While BPA-free products eliminate one known endocrine disruptor, they may contain substitutes like BPS or BPF, which exhibit similar biological effects. Additionally, other chemicals in plastics—such as phthalates or stabilizers—may also pose health risks. Look for bottles made from inert materials like glass or stainless steel for maximum safety.

How often should I replace my reusable water bottle?

Inspect your bottle monthly. Replace it if you notice cracks, cloudiness, persistent odor, or difficulty cleaning. For plastic reusable bottles, consider replacing every 6–12 months with heavy use. Stainless steel and glass bottles can last several years if maintained properly.

Conclusion: Making Informed Choices for Long-Term Health

Reusing plastic water bottles may seem like a small act of convenience or environmental responsibility, but the cumulative effects on health warrant attention. Scientific evidence shows that repeated use of single-use PET bottles can lead to increased exposure to microplastics, bacterial contamination, and low-level chemical leaching—especially under heat or poor hygiene conditions.

The safest approach is to reserve disposable plastic bottles for one-time use and transition to durable, easy-to-clean alternatives. By doing so, individuals protect not only their own health but also contribute to reducing plastic waste in a sustainable way. Awareness, proper cleaning, and informed material choices are key to maintaining safe hydration habits.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?