In the United States, tap water is generally considered one of the safest in the world due to strict federal regulations enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). However, safety can vary dramatically from city to city and state to state. Aging infrastructure, industrial contamination, agricultural runoff, and natural geology all influence what ends up in your glass. While most municipal systems meet EPA standards, recent crises in places like Flint, Michigan, and Jackson, Mississippi, have shaken public confidence.

This guide breaks down tap water safety across major U.S. regions, identifies common contaminants by area, and provides tailored filtration recommendations based on local risks. Whether you're relocating, traveling, or simply want peace of mind, understanding your region’s water profile is essential for making informed decisions about what you and your family consume daily.

Understanding Tap Water Regulation and Limitations

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), first passed in 1974 and amended several times since, empowers the EPA to set national health-based standards for over 90 contaminants in public water systems. These include microbes like Legionella, heavy metals such as lead and arsenic, nitrates, pesticides, and disinfection byproducts like trihalomethanes (THMs).

However, regulation doesn’t guarantee perfection. The EPA sets maximum contaminant levels (MCLs), but these are often compromises between health protection and feasibility. Some chemicals—like PFAS (“forever chemicals”)—were only recently added to monitoring requirements and aren't yet federally regulated at enforceable limits. Additionally, the SDWA applies only to public water systems serving 25 or more people year-round. Private wells, which serve about 13 million households, fall outside federal oversight entirely.

“Regulatory compliance doesn’t always equal optimal health protection. Many contaminants are legal below certain thresholds, but even low-level exposure over time can pose risks, especially for children and pregnant women.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Environmental Health Scientist, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Another critical gap: enforcement depends on self-reporting by utilities. In some rural or underfunded communities, testing may be infrequent or delayed. Infrastructure issues—such as corroded pipes leaching lead into water after it leaves treatment plants—are also common and not always reflected in official reports.

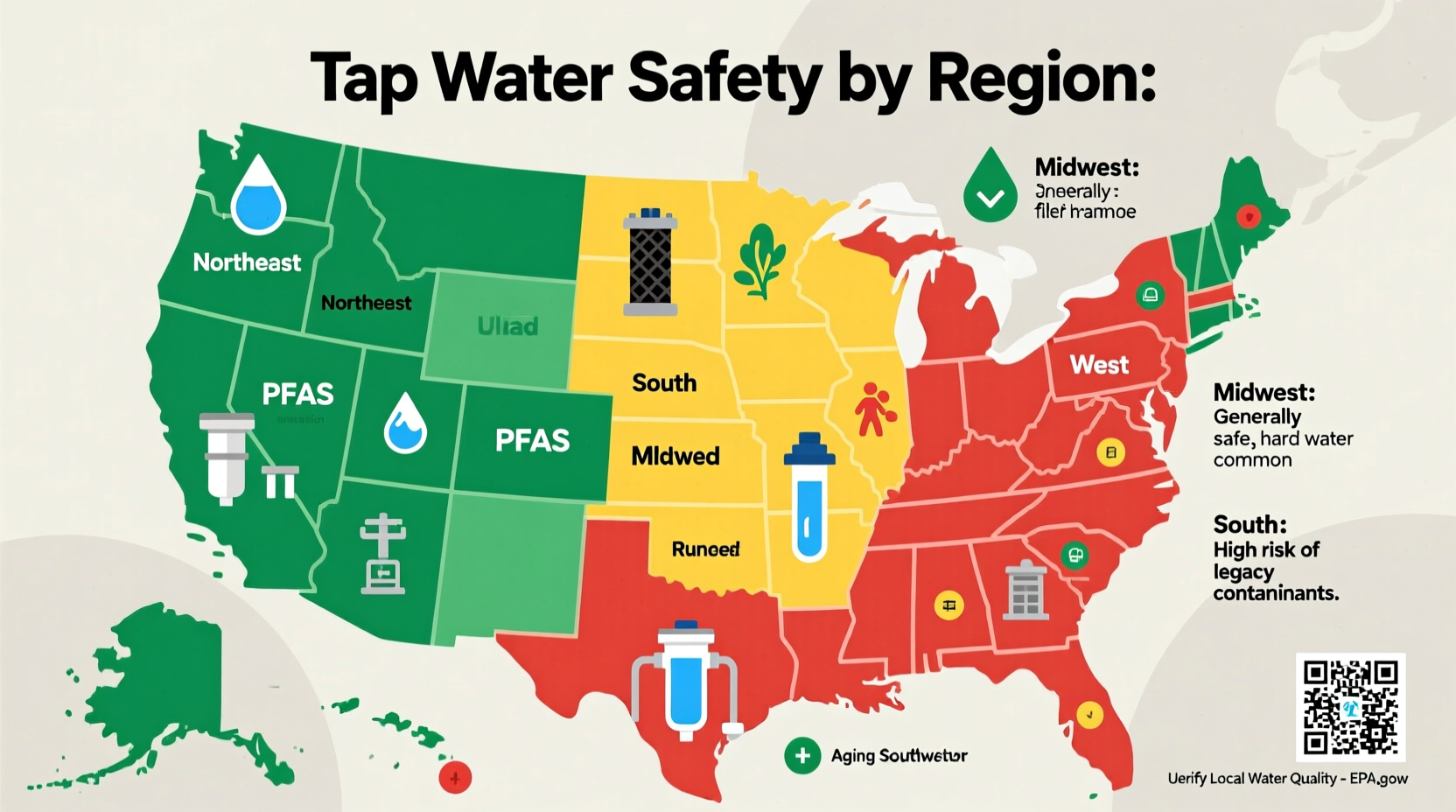

Regional Breakdown of Tap Water Safety and Risks

Water quality varies significantly depending on geography, source (surface vs. groundwater), industrial activity, and urban density. Below is a regional analysis highlighting typical concerns and real-world examples.

Northeast: Urban Infrastructure and Lead Exposure

States like New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts rely heavily on surface water from reservoirs and rivers. While treatment is advanced, aging service lines remain a serious concern. Cities such as Newark and Pittsburgh have faced lawsuits over elevated lead levels due to outdated plumbing.

Hard water (high mineral content) is common, leading to scale buildup but not health risks. Chloramine—a longer-lasting disinfectant—is widely used, which reduces bacterial growth but complicates home aquarium maintenance and may affect taste.

Midwest: Agricultural Runoff and Nitrates

The Midwest faces unique challenges from intensive farming. Fertilizers and manure contribute high levels of nitrates and nitrites, particularly in rural areas drawing from shallow aquifers. In Des Moines, Iowa, utility managers have battled nitrate spikes so severe they triggered emergency filtration measures.

Additionally, legacy industrial pollution has left pockets of contamination. Flint, Michigan’s lead crisis was caused by switching water sources without proper corrosion control. Even years later, trust remains low, and many residents still rely on bottled water.

South: Hard Water, Microbes, and Systemic Underfunding

In states like Texas, Alabama, and Mississippi, water sources range from brackish groundwater to reservoirs vulnerable to algal blooms. Hard water is widespread, increasing limescale and reducing appliance efficiency.

More troubling are systemic failures in smaller municipalities. Jackson, Mississippi’s repeated boil-water advisories stem from insufficient staffing, broken pumps, and decades of disinvestment. Climate change exacerbates these issues—extreme heat promotes bacterial growth, while flooding overwhelms treatment capacity.

West: Arsenic, PFAS, and Drought-Driven Concentration

Western states, particularly Arizona, Nevada, and California, frequently contend with naturally occurring arsenic in groundwater. Long-term exposure increases cancer risk. The EPA limit is 10 ppb, but studies show some private wells exceed 50 ppb.

PFAS contamination is another growing concern near military bases and industrial zones. In Colorado Springs, firefighting foam used at Peterson Air Force Base polluted local aquifers. Meanwhile, prolonged drought concentrates contaminants as water levels drop, intensifying salinity and toxin levels.

Pacific Northwest: Cleaner Sources but Emerging Threats

Oregon and Washington benefit from pristine mountain snowmelt feeding their systems. Overall, tap water here ranks among the nation's cleanest. However, wildfire smoke infiltration during fire season can introduce organic compounds and ash particles.

Some coastal communities face saltwater intrusion into aquifers due to over-pumping, requiring reverse osmosis treatment. Additionally, microplastics have been detected in rainwater and surface supplies, though health impacts remain under study.

Filtration Solutions by Region and Contaminant

No single filter works for every threat. Choosing the right system depends on your location, water source, and specific concerns. Below is a comparison of common filtration technologies and their effectiveness against regional contaminants.

| Filtration Type | Best For | Limited Against | Recommended Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon (Pitcher/Dispenser) | Chlorine, VOCs, taste/odor | Lead, nitrates, fluoride, microbes | Northeast, Pacific NW (low-risk areas) |

| Carbon Block (Under-Sink) | Lead, cysts, some PFAS, chlorine | Nitrates, hardness, arsenic | Urban Northeast, South cities |

| Reverse Osmosis (RO) | Lead, arsenic, nitrates, fluoride, PFAS, salts | VOCs (unless combined with carbon) | West, Midwest farm areas, South with hard water |

| Ion Exchange (Water Softener) | Hardness (calcium/magnesium), some radium | Most chemical contaminants | Texas, Southwest, Midwest |

| UV Purification | Bacteria, viruses, cysts | Chemicals, heavy metals, particulates | Rural South, private wells nationwide |

For comprehensive protection, multi-stage systems combining RO with UV and carbon polishing are ideal—especially for well owners or those in high-risk zones. Always verify certifications through NSF International or the Water Quality Association (WQA). Look for labels like NSF/ANSI 53 (health claims), 58 (RO), or 42 (aesthetic effects).

Action Plan: How to Assess and Improve Your Tap Water

Follow this step-by-step guide to ensure your household water is safe, regardless of where you live.

- Obtain Your Local Water Quality Report (CCR): Every utility must publish a Consumer Confidence Report by July 1 each year. Search “[Your City] + CCR” online or contact your provider directly.

- Review Key Contaminants: Focus on lead, nitrates, arsenic, PFAS, coliform bacteria, and disinfection byproducts. Note any violations or near-misses of MCLs.

- Test Your Home’s Water: Use a state-certified lab, especially if you’re on a well or suspect plumbing issues. Basic kits cost $20–$100; full panels run $150+. Order tests for lead, bacteria, nitrates, and local concerns (e.g., arsenic in the West).

- Evaluate Filtration Needs: Match your results to the appropriate technology. A carbon block filter suffices for chlorine and moderate lead; RO is better for multiple contaminants.

- Install and Maintain Filters: Replace cartridges per manufacturer guidelines—typically every 6–12 months. An expired filter can leach trapped contaminants back into water.

- Flush Pipes Before Use: Run cold water for 30–60 seconds if it hasn’t been used for 6+ hours. This clears stagnant water that may have absorbed lead from pipes.

Mini Case Study: The Hernandez Family in Tucson, Arizona

The Hernandez family moved to Tucson in 2022, excited about the desert landscape. After their infant developed mild rashes and fatigue, they suspected water issues. Their CCR showed arsenic at 8 ppb—below the federal limit but above the 1 ppb level recommended by health advocates.

They tested their tap water and found levels closer to 12 ppb due to localized well conditions. They installed a point-of-use reverse osmosis system under the kitchen sink. Within weeks, symptoms improved. Now, they use filtered water for drinking, cooking, and baby formula, and continue annual testing to monitor changes.

Essential Checklist for Safer Tap Water

- ✅ Obtain your latest Consumer Confidence Report

- ✅ Identify primary water source (surface, groundwater, well)

- ✅ Check for known local contaminants (lead, nitrates, PFAS, arsenic)

- ✅ Test water if on a private well or in an older home

- ✅ Choose a certified filter based on your risks

- ✅ Install and maintain filtration system properly

- ✅ Flush taps before using after long stagnation

- ✅ Re-test every 1–2 years or after major system changes

Frequently Asked Questions

Is bottled water safer than tap water?

Not necessarily. Bottled water is regulated by the FDA and often comes from municipal sources. It lacks the transparency of CCRs and contributes to plastic waste. For most Americans, filtered tap water is equally safe—and far more sustainable.

Can I rely solely on a refrigerator filter?

Refrigerator filters typically use basic carbon and reduce chlorine and particulates but don’t remove lead, nitrates, or PFAS effectively. Replace them every six months and consider upgrading if your water has known contaminants.

What should I do during a boil-water advisory?

Boiling kills bacteria and viruses but does not remove chemicals, lead, or nitrates. During advisories, use bottled water or a certified filter designed for microbial reduction. Follow local guidance closely and avoid using tap water for brushing teeth or preparing food until lifted.

Conclusion: Take Control of Your Water Safety

Tap water in the U.S. is largely safe, but “safe” doesn’t mean universally pure or risk-free. Geographic disparities, infrastructure decay, and emerging pollutants demand vigilance. Relying solely on government assurances is no longer enough—proactive testing and targeted filtration are key to protecting your health.

You don’t need to be a scientist to take meaningful action. Start with your CCR, assess your household’s risk factors, and invest in a filtration solution tailored to your region’s challenges. Clean water isn’t a luxury—it’s a foundation of wellness. Make informed choices today, and ensure every glass you pour supports a healthier tomorrow.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?