In recent years, blue light blocking glasses have surged in popularity. Marketed as a solution to digital eye strain, sleep disruption, and even long-term retinal damage, these amber- or yellow-tinted lenses now sit on the desks and nightstands of millions. Tech workers, gamers, students, and shift workers swear by them. But behind the sleek branding and influencer endorsements lies a critical question: Is there solid scientific evidence supporting their use, or is this just another wellness trend riding the wave of screen dependency?

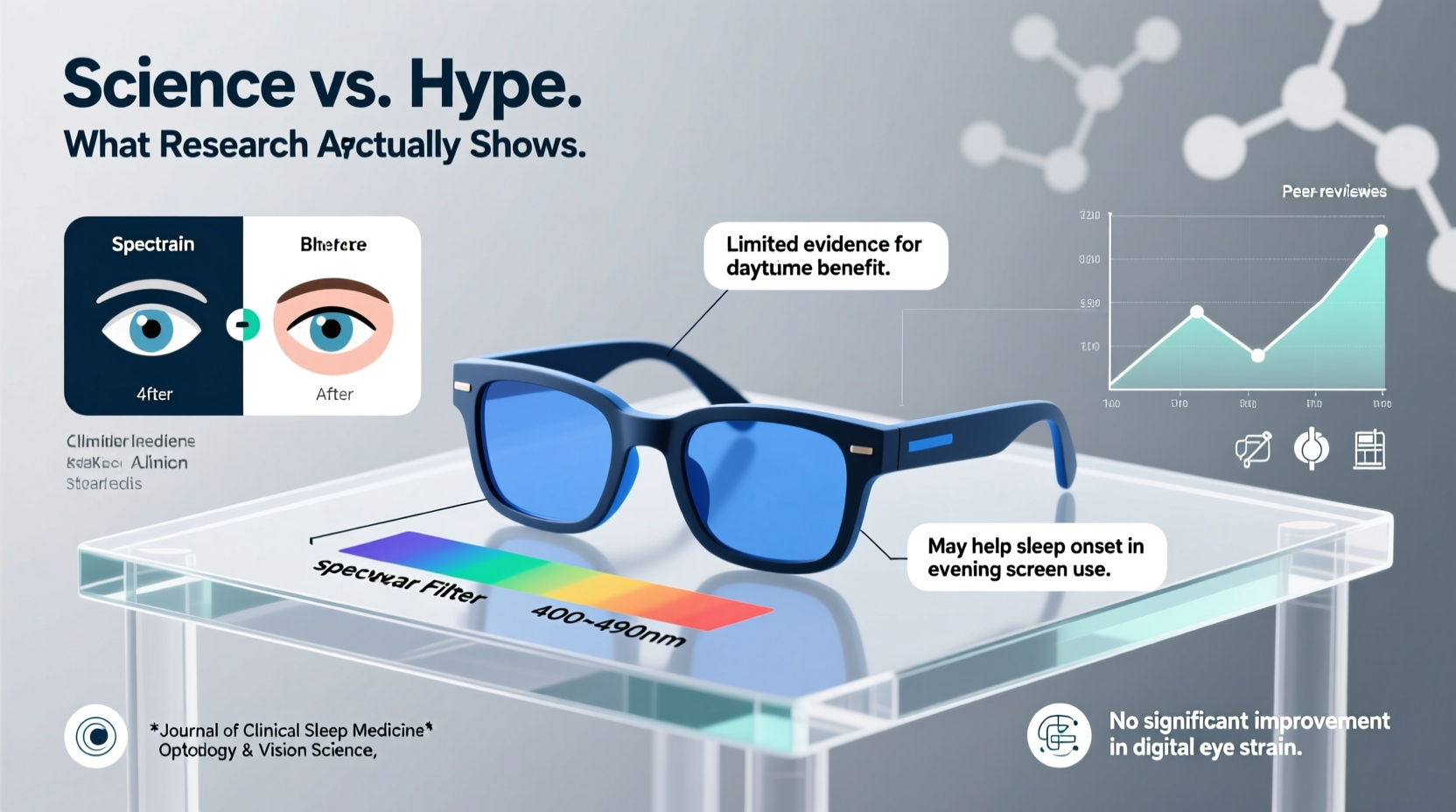

The answer isn’t a simple yes or no. While some studies suggest modest benefits—particularly for sleep regulation—others show little to no improvement in visual comfort or eye health. To separate fact from fiction, it’s essential to examine how blue light affects the body, what the research actually says about filtering it, and who might genuinely benefit from wearing these glasses.

Understanding Blue Light and Its Biological Impact

Blue light is part of the visible light spectrum, with wavelengths between approximately 380 and 500 nanometers. It’s naturally emitted by the sun and plays a crucial role in regulating circadian rhythms—the internal clock that governs sleep-wake cycles. Exposure to bright blue-rich daylight during the morning helps suppress melatonin, the hormone responsible for sleepiness, promoting alertness and cognitive function.

However, the concern arises not from natural sunlight but from artificial sources—especially LED screens (smartphones, computers, tablets) and energy-efficient lighting. These emit a disproportionate amount of blue light compared to traditional incandescent bulbs. The issue isn’t necessarily the intensity but the timing: exposure late at night can interfere with melatonin production, potentially delaying sleep onset and reducing sleep quality.

It’s important to note that not all blue light is harmful. Shorter wavelengths (around 460–480 nm) are most effective at suppressing melatonin and influencing circadian biology. Longer blue wavelengths (closer to green) are less disruptive. Many blue light glasses vary in the degree and range of filtration, which affects their real-world impact.

“Light is the most powerful synchronizer of our circadian clock. Evening exposure to blue-enriched light can delay sleep by up to an hour.” — Dr. Steven Lockley, Neuroscientist, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

What Does the Research Say About Blue Light Glasses?

The scientific literature on blue light blocking glasses presents a mixed but increasingly nuanced picture. Several randomized controlled trials have explored their effects on sleep, mood, and visual comfort—with varying results.

A 2017 study published in *Chronobiology International* found that participants who wore amber-tinted blue light glasses for three hours before bedtime experienced significant improvements in sleep quality and melatonin levels compared to a placebo group wearing clear lenses. Similar findings were reported in a 2020 trial involving office workers, where users reported falling asleep faster and feeling more rested after two weeks of evening use.

However, other studies show minimal or no benefit. A 2021 meta-analysis in *Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics* reviewed 15 clinical trials and concluded that while blue light filters may slightly improve subjective sleep quality, objective measures like total sleep time and sleep efficiency showed no consistent change. The authors noted that placebo effects and expectation bias likely play a significant role in user-reported benefits.

When it comes to digital eye strain—a common reason people buy these glasses—the evidence is even weaker. Symptoms like dry eyes, blurred vision, and headaches are primarily linked to prolonged screen use, poor ergonomics, infrequent blinking, and uncorrected vision problems—not blue light itself. The American Academy of Ophthalmology states that there is no scientific evidence that blue light from digital devices causes eye damage or contributes meaningfully to eye strain.

Who Might Actually Benefit From Blue Light Glasses?

While the average daytime screen user may not need blue light glasses, certain populations could see tangible benefits:

- Night shift workers: Individuals working overnight shifts often struggle with circadian misalignment. Wearing blue light blocking glasses during morning commutes can help preserve melatonin and improve daytime sleep quality.

- People with delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD): Those who naturally fall asleep very late may benefit from evening use of blue blockers to advance their sleep schedule.

- Individuals sensitive to light: Some people report heightened sensitivity to screen glare or brightness. Tinted lenses may reduce discomfort, though this is more about personal preference than biological necessity.

- Patients using light-sensitive medications: Certain drugs (e.g., tetracyclines, antipsychotics) increase photosensitivity. In such cases, filtering blue light may offer protective value.

For the general population using screens in the evening, behavioral changes—such as reducing screen brightness, enabling night mode, or setting device curfews—are equally effective and cost-free alternatives.

Comparing Solutions: Blue Light Glasses vs. Built-in Filters

| Solution | Effectiveness for Sleep | Impact on Eye Strain | Cost | User Convenience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amber-tinted blue light glasses | Moderate (especially if worn 2–3 hrs pre-bed) | Low to none | $20–$80 | High (if already wearing glasses) |

| Night Shift / f.lux software | Moderate (reduces blue tones) | Low | Free | Very high |

| Screen dimming + dark mode | Low to moderate | Moderate (reduces glare) | Free | Very high |

| Behavioral screen curfew (no screens 1 hr before bed) | High | High | Free | Medium (requires discipline) |

This comparison shows that while blue light glasses can be helpful, they are neither the most effective nor the most accessible option for most people. Software-based solutions and habit changes often deliver comparable or better results at no cost.

Common Misconceptions and Marketing Myths

The rise of blue light glasses has been accompanied by several persistent myths:

- Myth: Blue light damages your eyes. There is no strong evidence that screen-emitted blue light causes retinal damage in humans. Laboratory studies exposing retinal cells to intense blue light do not reflect real-world conditions.

- Myth: Everyone needs blue light protection. For most people, especially those exposed to screens during daylight hours, blue light exposure is beneficial for alertness and mood.

- Myth: Clear lenses with “blue light coating” are effective. Most clear computer glasses block only a small fraction of blue light (10–20%) and are unlikely to influence circadian rhythms.

- Myth: Blue light glasses eliminate digital eye strain. Eye strain is multifactorial. Solutions include taking breaks (20-20-20 rule), optimizing screen distance, and ensuring proper prescription eyewear.

Marketing often exaggerates benefits using terms like “retina protection” or “anti-fatigue,” which sound scientific but lack clinical backing. Consumers should scrutinize claims and look for third-party testing data on spectral transmittance when purchasing.

Mini Case Study: Sarah, the Nighttime Scroller

Sarah, a 32-year-old project manager, struggled with insomnia despite going to bed at 10:30 PM. She routinely used her phone in bed, scrolling through social media under bright overhead lights. After reading about blue light glasses, she purchased a pair with amber lenses and wore them starting at 8 PM.

Within a week, she reported falling asleep 20–30 minutes earlier. However, when she participated in a sleep tracking study, her total sleep time increased by only 12 minutes, and her sleep efficiency remained unchanged. Researchers noted that her improved perception of sleep was likely due to both psychological reassurance and reduced screen brightness—she instinctively lowered her phone’s brightness when wearing the glasses.

The takeaway: Behavioral changes played a bigger role than the glasses themselves. When Sarah later replaced the glasses with a strict “no screens after 9 PM” rule, her sleep improved more significantly.

Expert Tips for Managing Screen Light Exposure

- Limit screen use 1–2 hours before bedtime. This is the single most effective way to support natural melatonin release.

- Optimize room lighting. Replace cool-white LEDs with warm-white bulbs in bedrooms and living areas used at night.

- Take regular visual breaks. Follow the 20-20-20 rule: every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds.

- Adjust screen settings. Lower brightness to match ambient light and enable dark mode where possible.

- Consider glasses—if behavior change isn’t feasible. For shift workers or those required to use screens late at night, blue light glasses can be a practical tool.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do blue light blocking glasses really work?

They can help improve sleep onset when worn consistently in the evening, particularly for individuals exposed to bright screens at night. However, their effect on eye strain and long-term eye health is unsupported by strong evidence.

Can I wear blue light glasses during the day?

Not recommended for most people. Daytime exposure to blue light helps maintain alertness, mood, and circadian rhythm. Wearing tinted glasses during daylight hours may lead to grogginess or disrupted sleep patterns.

Are there any risks to using blue light glasses?

Physical risks are minimal, but over-reliance on them may distract from more effective strategies like reducing screen time or improving sleep hygiene. Additionally, cheaply made glasses may distort color perception or cause visual discomfort.

Conclusion: Weighing Science Against Hype

The hype around blue light blocking glasses exceeds the current scientific consensus. While they offer measurable benefits for specific groups—particularly those with circadian rhythm disruptions—their widespread promotion as a universal remedy for screen-related issues is overstated. For the average user, free, behavior-based interventions are more effective and sustainable.

That said, if wearing blue light glasses encourages healthier screen habits—like turning off devices earlier or dimming lights—they serve a valuable psychological function. The key is to view them not as a medical solution but as one tool among many for managing digital well-being.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?