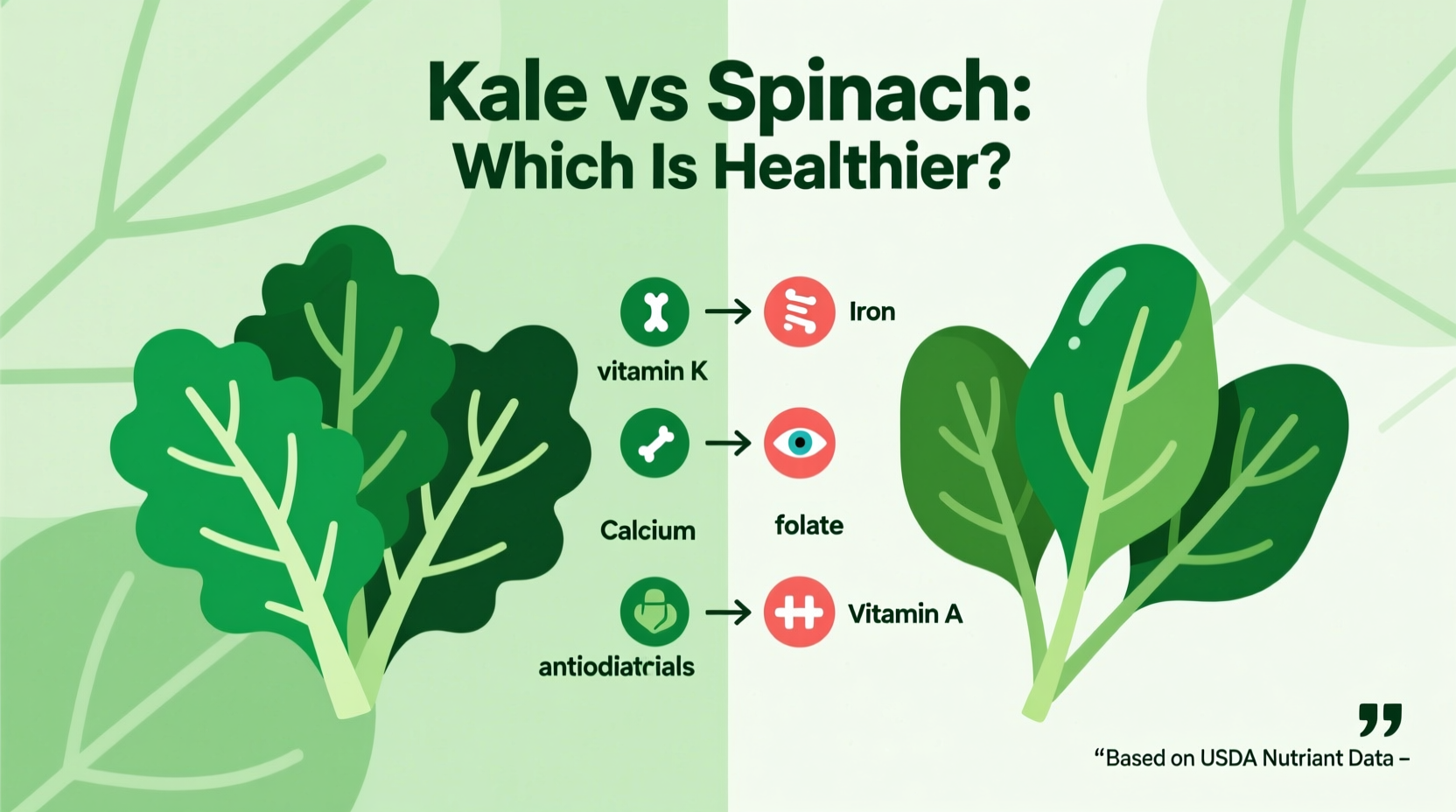

When it comes to nutrient-dense leafy greens, kale and spinach consistently top the list. Both are staples in health-conscious kitchens, praised for their high vitamin content, antioxidant properties, and versatility in cooking. But when placed side by side, which one truly deserves the crown as the healthier choice? The answer isn't straightforward—it depends on your nutritional goals, cooking methods, and dietary needs. While both greens offer impressive benefits, they differ significantly in nutrient profiles, digestibility, flavor, and culinary applications. Understanding these differences empowers you to make informed decisions that align with your wellness objectives and culinary preferences.

Definition & Overview

Kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) is a hardy, dark green leafy vegetable belonging to the cabbage family. Known for its ruffled or curly leaves and fibrous stem, kale thrives in cooler climates and has been cultivated for centuries, particularly in Europe. It's available in several varieties, including curly kale, Lacinato (also called dinosaur or Tuscan kale), and red Russian kale. Kale has a robust, slightly bitter, and earthy flavor that mellows with cooking or proper preparation.

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) is a fast-growing, tender leafy green native to Central and Western Asia. Introduced to Europe in the 12th century, it gained widespread popularity for its mild taste and soft texture. Spinach leaves are broad, smooth, and deep green, ranging from delicate baby leaves to larger, more mature forms. It has a subtly sweet, grassy flavor and can be eaten raw or lightly cooked without overwhelming other ingredients.

Both vegetables are classified as non-starchy, low-calorie vegetables rich in phytonutrients. They are central to plant-forward diets and frequently recommended by nutritionists for their role in reducing inflammation, supporting eye health, and promoting cardiovascular function. However, their biochemical compositions lead to different impacts on digestion, mineral absorption, and overall health outcomes.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Kale | Spinach |

|---|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Earthy, slightly bitter, peppery (especially raw) | Mild, subtly sweet, grassy |

| Texture | Firm, fibrous, chewy (requires massaging or cooking) | Tender, delicate, softens quickly when heated |

| Color | Deep green to blue-green | Bright to dark green |

| Shelf Life (Refrigerated) | 5–7 days (longer if stems removed and stored dry) | 3–5 days (prone to wilting and spoilage) |

| Culinary Function | Base for salads, sautéed dishes, soups, chips | Raw salads, smoothies, quiches, pasta fillings, wilted sides |

| Best Cooking Methods | Sautéing, roasting, steaming, massaging (for raw use) | Quick sautéing, steaming, blending, raw consumption |

Nutritional Comparison: Micronutrients That Matter

The true distinction between kale and spinach lies in their micronutrient density. While both are low in calories—about 30–40 kcal per cooked cup—they deliver vastly different amounts of key vitamins and minerals. Here’s a comparison based on a 1-cup (cooked) serving:

| Nutrient | Kale (1 cup, cooked) | Spinach (1 cup, cooked) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K | 1062 mcg | 889 mcg | Essential for blood clotting and bone health; both exceed daily needs |

| Vitamin A (RAE) | 885 mcg | 943 mcg | Supports vision, immune function, skin health |

| Vitamin C | 53 mg | 25 mg | Kale provides over twice the vitamin C—important for immunity and iron absorption |

| Calcium | 177 mg | 245 mg | Spinach contains more, but bioavailability is limited due to oxalates |

| Iron | 1.2 mg | 6.4 mg | Spinach has five times more iron, though non-heme iron requires vitamin C for absorption |

| Magnesium | 33 mg | 157 mg | Spinach is superior for muscle function and nerve regulation |

| Potassium | 296 mg | 839 mg | Spinach supports heart health and electrolyte balance more effectively |

| Folate (B9) | 28 mcg | 263 mcg | Crucial for DNA synthesis and fetal development; spinach excels here |

| Oxalate Content | Low to moderate | High | High oxalates in spinach may contribute to kidney stones in susceptible individuals |

This data reveals a critical insight: while spinach wins in total iron, magnesium, potassium, and folate, much of these minerals are bound by oxalic acid, reducing their bioavailability. Kale, though lower in some minerals, offers better-absorbed calcium and higher levels of vitamin C, which enhances the absorption of plant-based iron when consumed together.

Practical Usage: How to Use Each Green Effectively

Choosing between kale and spinach often comes down to how you plan to use them in meals. Their textures and flavor intensities dictate optimal applications.

Using Kale in the Kitchen

Kale’s sturdy structure makes it ideal for dishes that require longer cooking or holding up to dressings. Because raw kale can be tough and bitter, preparation techniques matter.

- Massaged Kale Salads: Tear leaves into bite-sized pieces, remove tough stems, and massage with olive oil, lemon juice, and salt for 2–3 minutes. This softens the fibers and reduces bitterness, creating a tender base for grain bowls or winter salads.

- Sautéed or Stir-Fried: Cook chopped kale in garlic-infused oil over medium heat for 5–7 minutes until wilted but still vibrant. Add a splash of vinegar or citrus at the end to brighten flavor.

- Smoothies: Use young, tender kale leaves (not stems) in fruit-heavy smoothies. Pair with banana, pineapple, or mango to mask bitterness. The high vitamin C content complements iron absorption from other ingredients like chia or oats.

- Oven-Baked Chips: Toss torn kale with olive oil and sea salt, then bake at 300°F (150°C) for 15–20 minutes until crisp. Avoid overcrowding the tray for even crisping.

- Soups and Stews: Add chopped kale during the last 10 minutes of cooking to retain texture and nutrients. Especially effective in bean soups, minestrone, or lentil stews.

Tip: To maximize nutrient retention, avoid boiling kale for extended periods. Steaming or quick sautéing preserves glucosinolates—compounds linked to cancer prevention.

Using Spinach in the Kitchen

Spinach’s tenderness allows for minimal processing, making it ideal for quick meals and raw applications.

- Raw Salads: Baby spinach is perfect for mixed greens. Combine with strawberries, goat cheese, nuts, and balsamic vinaigrette for a balanced dish rich in antioxidants and healthy fats.

- Wilted Spinach: Heat a skillet with olive oil, add minced garlic, then toss in fresh spinach. Stir for 1–2 minutes until just collapsed. Season with lemon zest and black pepper. Ideal as a side or added to omelets.

- Blended Dishes: Incorporate raw or lightly steamed spinach into pasta sauces, dips (like spinach-artichoke), or casseroles. Its mild flavor doesn’t overpower other ingredients.

- Baking Fillings: Use in spanakopita, lasagna, or stuffed chicken breasts. Pre-cook and drain well to prevent excess moisture.

- Smoothies: One of the most seamless ways to consume spinach—its neutral taste disappears when blended with fruits. A cup adds fiber, folate, and iron without altering flavor.

Tip: When cooking spinach, remember it shrinks dramatically—6 cups raw yield about 1 cup cooked. Plan portions accordingly.

Variants & Types

Both kale and spinach come in multiple forms, each suited to specific culinary purposes.

Kale Varieties

- Curly Kale: Most common in supermarkets. Ruffled, frilly leaves with a strong, slightly bitter taste. Best when cooked or massaged.

- Lacinato (Dinosaur/Tuscan) Kale: Flat, dark blue-green leaves with a pebbled texture. More tender and less bitter than curly kale. Excellent in soups like ribollita or shaved raw into salads.

- Red Russian Kale: Purple-veined, flat leaves with a sweeter, almost nutty flavor. More cold-tolerant and delicate—ideal for raw preparations.

- Young/Kale Microgreens: Harvested early, these are milder and packed with concentrated nutrients. Used as garnishes or in sprouted salads.

Spinach Varieties

- Baby Spinach: Harvested young, with tender leaves and a sweet flavor. Perfect for raw eating, sandwiches, and quick sautés.

- Flat-Leaf (Savoy) Spinach: Crinkly, dark green leaves. More robust than baby spinach, suitable for cooking. Requires thorough washing due to dirt trapping in crevices.

- Smooth-Leaf Spinach: Easier to clean than savoy types. Often used in canned or frozen products.

- Frozen Spinach: Blanching before freezing preserves nutrients. Convenient for cooking; always thaw and squeeze out excess water before use.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Kale and spinach are often grouped with other leafy greens, but key distinctions set them apart.

| Green | Differences from Kale | Differences from Spinach |

|---|---|---|

| Swiss Chard | Milder than kale, colorful stems, less fibrous. Cooks faster. | Slightly earthier than spinach; stems require separate cooking. |

| Collard Greens | Even tougher than kale; traditionally slow-cooked in Southern cuisine. | Less tender than spinach; not suitable for raw use. |

| Arugula | Peppery but much smaller and more delicate; never cooked like kale. | Used exclusively raw; stronger flavor than spinach. |

| Romaine Lettuce | Very low in nutrients compared to kale; used only raw. | Higher water content, crunchier texture, less nutritious than spinach. |

“The best green is the one you’ll actually eat. Consistency trumps perfection. Rotate kale and spinach to benefit from their complementary nutrient profiles.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Registered Dietitian and Plant-Based Nutrition Specialist

Practical Tips & FAQs

Should I eat kale or spinach raw?

Spinach is generally safer and more pleasant raw due to its tenderness and lower goitrogen content. Raw kale contains goitrogens—compounds that may interfere with thyroid function in large quantities—especially concerning for those with hypothyroidism. Light cooking deactivates these compounds. If consuming raw kale regularly, pair it with iodine-rich foods like seaweed or dairy.

Which is better for weight loss?

Both are excellent choices—low calorie, high fiber, and nutrient-dense. Spinach has a slight edge in volume due to its softer texture, allowing larger portions. However, kale’s higher fiber and vitamin C content may support metabolism and satiety more effectively.

Can I substitute one for the other?

In cooked dishes, yes—with adjustments. Replace spinach with kale in soups or stir-fries, but extend cooking time. For raw applications, swap kale for spinach only if massaged or finely shredded. Never substitute raw curly kale 1:1 in delicate salads.

How should I store them?

- Kale: Remove from plastic bag, wrap in dry paper towels, and store in a sealed container for up to 7 days.

- Spinach: Keep in original packaging or breathable container. Do not wash until ready to use. Wilts quickly if exposed to moisture.

Is frozen spinach as good as fresh?

Yes, especially for cooking. Frozen spinach is blanched and preserved at peak ripeness, retaining most nutrients. It’s often more affordable and convenient. Just be sure to thaw and drain thoroughly to avoid watery dishes.

Which is better for smoothies?

Spinach wins for flavor neutrality. Kale offers more vitamin C and calcium but can impart bitterness. For beginners, start with spinach; as your palate adapts, blend in small amounts of kale for added nutrition.

Does cooking destroy nutrients?

Some nutrients degrade with heat (e.g., vitamin C), while others become more available (e.g., beta-carotene). Steaming or stir-frying preserves more nutrients than boiling. Overall, both cooked and raw forms provide substantial health benefits.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Kale and spinach are both nutritional powerhouses, but their strengths serve different purposes:

- Choose kale when you want higher vitamin C, better calcium bioavailability, and a hearty green for cooking or massaged salads. It’s ideal for immune support and adding bulk to meals.

- Choose spinach for superior iron, magnesium, folate, and potassium content. Its mildness makes it perfect for raw consumption, blending, and dishes where subtlety is key. Be mindful of oxalate content if prone to kidney stones.

- Rotate both to gain a broader spectrum of phytonutrients and avoid overexposure to any single compound.

- Prepare appropriately: Massage kale, cook spinach lightly, and combine with healthy fats and vitamin C sources to maximize absorption.

- No single green is “healthier” overall—the best choice depends on your health goals, taste preferences, and culinary context.

Experiment this week: Make a massaged kale salad on Monday and a spinach frittata on Wednesday. Notice the differences in texture, satiety, and energy levels. Your body will guide you to your ideal green.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?