For generations, soups and stews have warmed kitchens across cultures, offering comfort, nourishment, and culinary versatility. Yet despite their shared heritage and overlapping ingredients, they are distinct in form, function, and technique. Confusion often arises—especially in casual conversation—where the terms are used interchangeably. Understanding the real differences isn’t just a matter of semantics; it affects how dishes are prepared, served, and even perceived. Whether you're building a weeknight meal or planning a slow-cooked centerpiece for Sunday dinner, knowing when to make a soup versus a stew ensures better results, improved textures, and more satisfying flavors.

Definition & Overview: What Are Soup and Stew?

Soup is a liquid-based dish typically made by simmering ingredients—such as vegetables, meat, legumes, or grains—in broth, stock, or water. It ranges from clear broths like consommé to creamy purées like bisque or chowder. The defining characteristic of soup is its high liquid-to-solid ratio, which allows it to be easily sipped from a bowl or ladled with a spoon without requiring a fork.

Stew, by contrast, is a hearty, thick preparation where solid ingredients—usually meat, poultry, or root vegetables—are slowly cooked in a smaller amount of liquid until tender. The result is a rich, cohesive mixture where the solids dominate both volume and texture. Stews rely on prolonged, moist-heat cooking to break down tough cuts of meat and develop deep flavor, with the sauce serving as a complement rather than the main component.

Both dishes originate in practicality. Early human civilizations developed soup as an efficient way to combine available ingredients into a digestible, warming meal using minimal fuel. Stewing evolved similarly but focused on transforming less desirable, fibrous cuts of meat into tender, flavorful fare through slow, low-temperature cooking. Today, these preparations span global cuisines—from French bouillon to Moroccan tagine, Japanese miso to Hungarian goulash—each reflecting regional tastes and traditions while adhering to core structural principles.

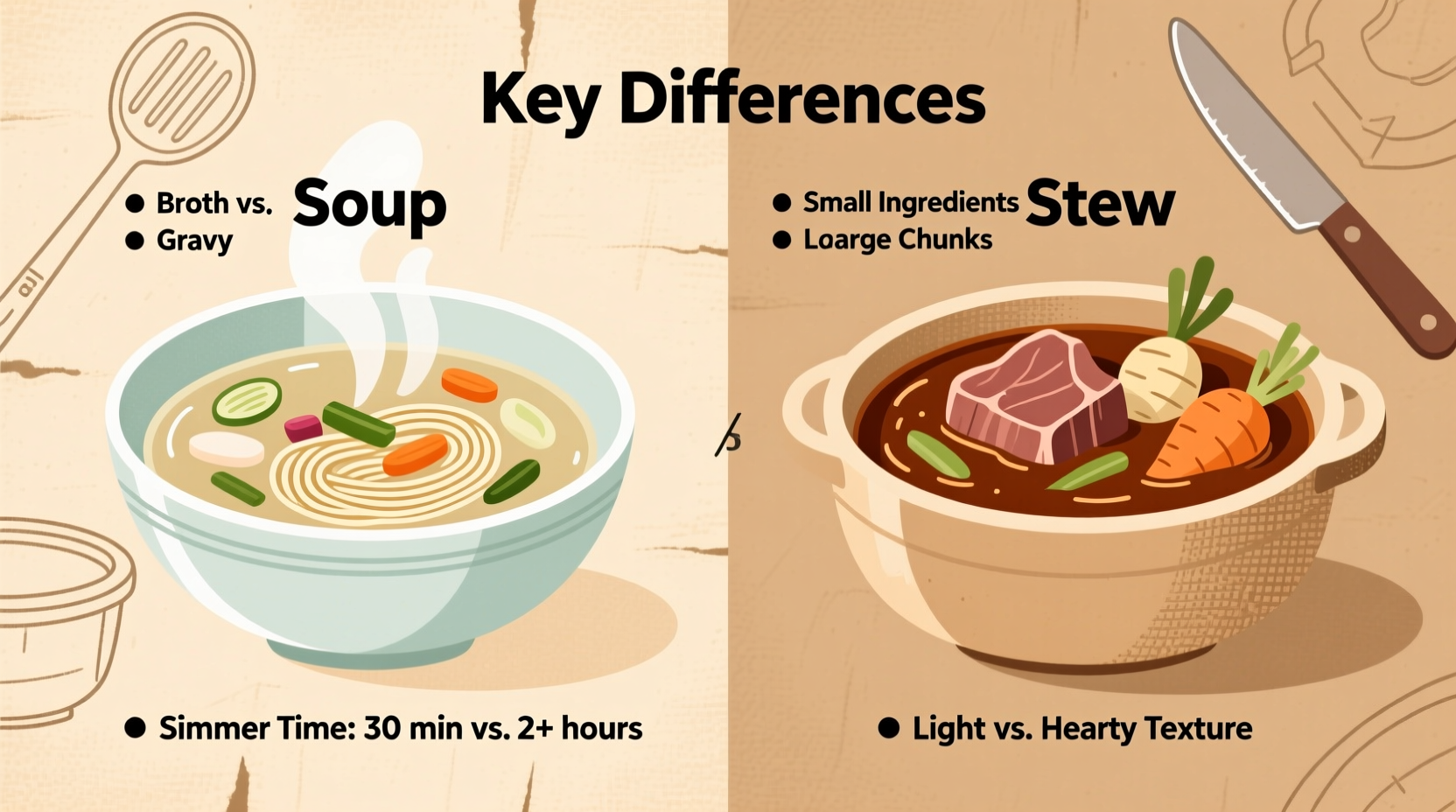

Key Characteristics: How to Tell Them Apart

The distinction between soup and stew goes beyond naming convention. Several measurable factors define each category:

| Feature | Soup | Stew |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Content | High — typically 60–80% of the dish | Low to moderate — usually 30–50% |

| Texture | Fluid, pourable, often thin or silky | Thick, chunky, requires a fork or spoon to eat solids |

| Main Ingredients | Balanced mix of solids and liquid; small ingredient cuts | Large, hearty chunks; emphasis on protein and vegetables |

| Cooking Time | Short to medium (15 mins – 2 hours) | Long (2–6+ hours), especially for meat-based versions |

| Thickening Method | Roux, cream, purée, starch slurry (optional) | Natural gelatin from collagen breakdown; sometimes flour dredging or reduction |

| Serving Vessel | Bowl or cup, often with handle | Deep plate or wide bowl, eaten with utensils |

| Primary Role | Appetizer, light meal, or side | Main course, center-of-the-plate dish |

This table underscores a fundamental truth: soup emphasizes liquidity and balance, while stew prioritizes substance and depth. A bowl of chicken noodle soup floats pieces of chicken and pasta in a clear broth—designed to soothe and hydrate. A beef stew, meanwhile, features large cubes of meat and vegetables suspended in a glossy, reduced sauce that clings to every morsel.

Practical Usage: When to Make Soup vs. Stew

Choosing between soup and stew depends on your goals: time, ingredients, season, and desired outcome.

Soup: Flexibility and Speed

Soups excel when you need something quick, adaptable, and light. They’re ideal for using up vegetable scraps, wilting greens, or repurposing leftover proteins. A well-made stock can transform odds and ends into a satisfying meal within 30 minutes.

- Weeknight dinners: Tomato basil soup with grilled cheese, lentil soup with crusty bread.

- Illness recovery: Clear broths help rehydrate and soothe sore throats.

- Appetizers: Serve small portions before a main course (e.g., chilled gazpacho).

- Vegetarian/vegan focus: Vegetable-based soups shine without needing animal protein.

To build a balanced soup, start with a flavorful base—homemade stock, canned broth, or water enhanced with aromatics. Sauté onions, carrots, and celery (mirepoix) to build foundation flavor. Add liquids and primary ingredients, then season gradually. Finish with fresh herbs, citrus zest, or a drizzle of oil for brightness.

Stew: Depth Through Patience

Stews demand more time but reward with complexity and richness. They are best suited for weekends or batch cooking, where long simmering develops flavor and tenderizes inexpensive cuts of meat.

- Cold weather meals: Hearty stews provide sustained energy and warmth.

- Budget cooking: Tough cuts like chuck roast, oxtail, or lamb shank become meltingly tender.

- Meal prep: Stews improve over days as flavors meld.

- Global specialties: Coq au vin, Irish stew, Nigerian okra stew.

For optimal stew-making, sear meat first to create fond—the browned bits at the bottom of the pot that add umami depth. Deglaze with wine or stock, then return meat to the pot with vegetables and enough liquid to partially submerge ingredients. Cover and simmer gently—never boil—to prevent toughness. Skim fat periodically, and adjust seasoning at the end.

Pro Tip: For thicker stew sauce without flour, remove the lid during the last 30–60 minutes of cooking to allow natural reduction. The gelatin released from connective tissues will give the sauce body and a luxurious mouthfeel.

Variants & Types: Regional and Textural Differences

Both soup and stew come in numerous forms, shaped by geography, climate, and tradition.

Common Types of Soup

- Clear Soups – Broths and consommés with visible separation between liquid and solids. Examples: chicken noodle, Vietnamese pho.

- Cream Soups – Thickened with dairy, roux, or puréed vegetables. Examples: clam chowder, broccoli bisque.

- Puréed Soups – Cooked ingredients blended until smooth. Examples: pumpkin soup, split pea.

- Chilled Soups – Served cold, often fruit- or vegetable-based. Examples: gazpacho, vichyssoise.

- International Variants – Miso (Japan), borscht (Ukraine), tom yum (Thailand).

Common Types of Stew

- Brown Stews – Meat seared first, cooked in dark liquid (stock, wine). Examples: beef bourguignon, daube.

- White Stews (Blanquettes) – Meat not seared; pale color from white stock or milk. Example: blanquette de veau.

- Dry Stews – Minimal liquid, almost braised. Common in Middle Eastern and African cuisines. Example: Ethiopian doro wat.

- Fish/Seafood Stews – Quick-cooking but structured like stews. Examples: bouillabaisse, cioppino.

- Vegetable Stews – Focused on root vegetables and legumes. Example: Turkish turlu.

The line blurs occasionally—bouillabaisse, for instance, is called a stew in France but has a broth-rich profile akin to soup. However, its serving method—with fish and potatoes as central components and broth poured over croutons separately—aligns more closely with stew presentation.

Comparison with Similar Dishes

Misclassification is common. Here’s how soup and stew differ from other liquid-based dishes:

| Dish | How It Differs from Soup | How It Differs from Stew |

|---|---|---|

| Bisque | A type of cream soup, but always shellfish-based and heavily puréed with rice or crustacean shells for thickness. | Too smooth and liquid-heavy; lacks chunky solids. |

| Braise | Less liquid than most soups; primary goal is tenderizing meat, not creating a drinkable broth. | Similar technique, but braises often feature one large piece (e.g., pork shoulder), while stews use cubed ingredients. |

| Chili | Thicker and heartier than typical soups; rarely sipped. | Often classified as a stew due to low liquid and dominant solids, though some tomato-heavy versions lean toward soup. |

| Gumbo | Served with rice; broth is secondary to roux-thickened base and proteins. | More complex thickener (roux, okra, filé powder); functions as both soup and stew depending on style. |

These comparisons reveal that categorization isn’t always rigid. Culinary evolution has created hybrid dishes, but understanding the core principles helps maintain technique integrity.

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can a soup become a stew—or vice versa?

Yes, through manipulation of liquid and cooking time. Reducing soup by simmering uncovered increases concentration and thickness, potentially turning a broth-heavy dish into a stew-like preparation. Conversely, adding liquid to a stew transforms it into a soup, though flavor may dilute unless additional seasoning is applied.

How do I thicken soup without making it stew-like?

Use a slurry (cornstarch + cold water), roux, or purée part of the vegetables. Avoid over-reducing, which concentrates solids and shifts the balance toward stew territory.

Is chili a soup or a stew?

Most culinary experts classify chili as a stew—particularly Texas-style, which contains minimal liquid and no beans. Bean-inclusive versions have higher moisture but still emphasize solid ingredients and are served as main courses.

Do stews always require meat?

No. Vegetarian stews using beans, lentils, mushrooms, and root vegetables achieve similar texture and heartiness. A well-made lentil stew with carrots, onions, and tomatoes mimics the mouthfeel and satisfaction of meat-based versions.

What’s the best pot for each?

Use a tall stockpot or Dutch oven for soups to accommodate volume and prevent splashing. For stews, a heavy-bottomed Dutch oven is ideal—it distributes heat evenly and supports searing, deglazing, and slow simmering.

How long do they last in storage?

- Soup: 3–4 days in the refrigerator; up to 6 months frozen.

- Stew: 4–5 days refrigerated; flavors deepen over 2–3 days. Freeze for up to 3 months.

“The difference between soup and stew is not in the recipe, but in the intention. Soup invites you to sip, to warm from within. Stew demands you dig in, to engage with every bite.” — Chef Elena Martinez, James Beard nominee and author of Rooted Kitchens

Summary & Key Takeaways

The distinction between soup and stew lies in structure, not just ingredients. Recognizing these differences enhances both cooking precision and dining experience.

- Soup is defined by its liquid dominance—it should flow freely and be consumable primarily by spoon or sip.

- Stew is characterized by its solidity—chunky ingredients in a clinging sauce, meant to be eaten like a main course.

- Cooking technique follows form: soups favor quicker methods; stews rely on slow transformation.

- Hybrids exist, but understanding the baseline helps maintain authenticity and control outcomes.

- Seasonality and purpose guide choice: opt for soup in spring and summer for lightness; choose stew in colder months for sustenance.

Try This at Home: Make two versions of chicken and vegetables—one as soup, one as stew—using the same base ingredients. Simmer one with ample broth and small cuts for 30 minutes; cook the other with half the liquid, larger pieces, and a two-hour simmer. Taste the contrast in texture, temperature retention, and satiety. You’ll feel the difference.

Mastering the nuances between soup and stew empowers cooks to make intentional choices in the kitchen. Whether crafting a delicate consommé or a robust lamb ragù, understanding these foundational categories elevates everyday meals into expressions of culinary intelligence.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?