The human heart is a marvel of biological engineering, designed to pump blood efficiently throughout the body. While all four chambers play essential roles, the two ventricles—left and right—differ significantly in structure, particularly in wall thickness. The left ventricle is notably thicker than the right. This isn't a random anatomical quirk; it's a critical adaptation that ensures the body receives oxygenated blood under sufficient pressure. Understanding why this difference exists sheds light on cardiovascular function, disease risk, and overall circulatory efficiency.

Anatomical Differences Between Left and Right Ventricles

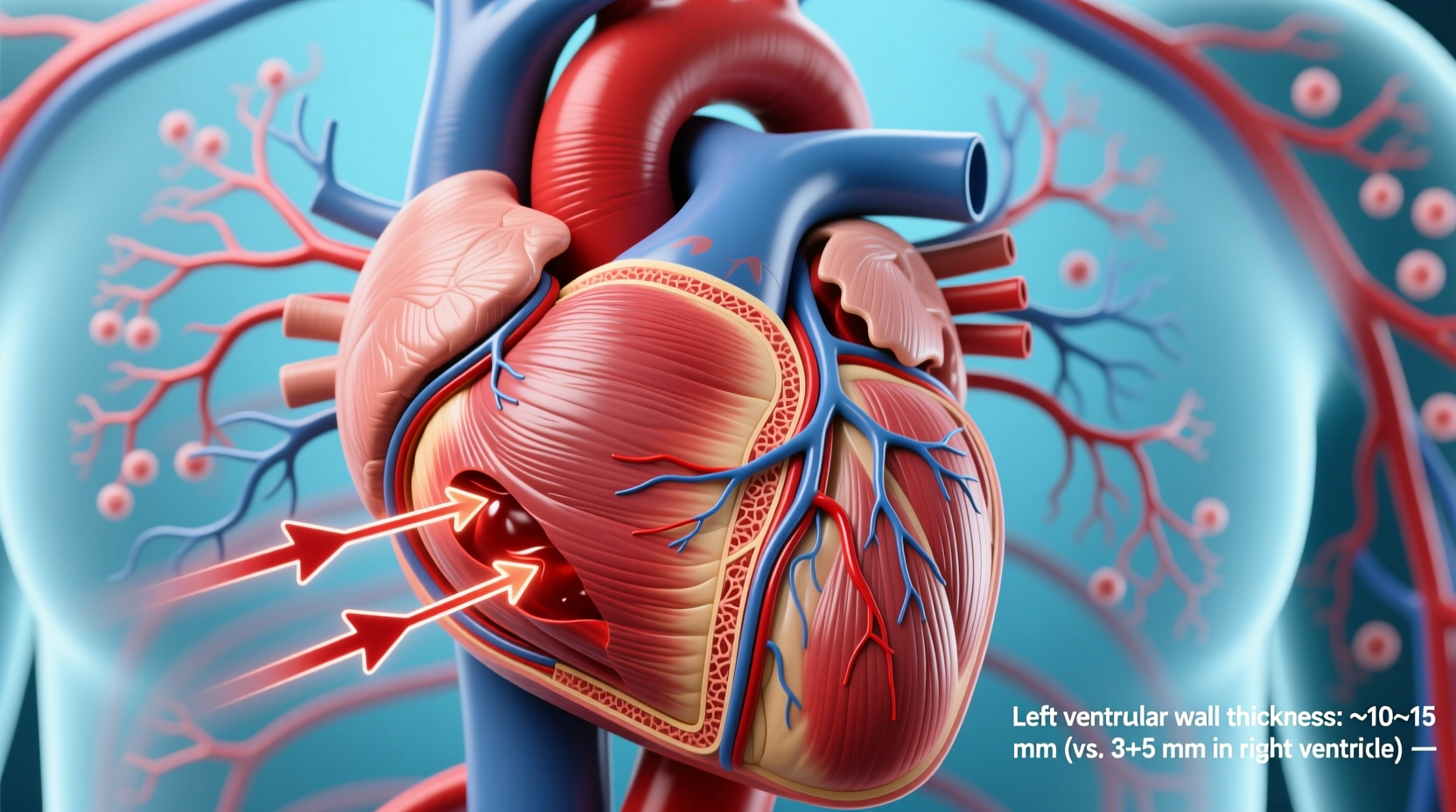

The heart’s ventricles are responsible for pumping blood out of the heart, but they serve different circulatory systems. The right ventricle sends deoxygenated blood to the lungs via the pulmonary artery, a low-pressure system. In contrast, the left ventricle propels oxygen-rich blood into the aorta, from where it travels through the entire body—a high-pressure demand requiring much greater force.

This functional disparity directly influences muscle mass. The left ventricular wall typically measures between 8 to 12 millimeters in thickness in healthy adults, while the right ventricular wall is only about 3 to 5 millimeters thick. This near doubling of muscle mass allows the left ventricle to generate systolic pressures averaging around 120 mmHg, compared to the right ventricle’s output of approximately 25 mmHg.

| Ventricle | Wall Thickness (mm) | Pumping Pressure (mmHg) | Circulation System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left Ventricle | 8–12 | ~120 | Systemic |

| Right Ventricle | 3–5 | ~25 | Pulmonary |

This table illustrates the direct relationship between workload and muscular development. Evolution has optimized each chamber for its specific role: economy of effort on the right, power generation on the left.

Functional Demands Driving Muscle Development

The primary reason for the left ventricle’s increased thickness lies in the resistance it must overcome. Systemic circulation spans thousands of miles of arteries, arterioles, and capillaries, creating substantial vascular resistance. To maintain adequate perfusion to vital organs like the brain, kidneys, and muscles, blood must be ejected with enough force to travel long distances against gravity and friction.

In contrast, the pulmonary circuit is short and offers far less resistance. Blood flows from the heart to the lungs and back with minimal pressure drop. As a result, the right ventricle does not need to develop thick walls to fulfill its duty. It functions more like a volume pump than a pressure generator.

“Cardiac muscle adapts precisely to hemodynamic load. The left ventricle’s hypertrophy is not pathological by default—it’s physiological necessity.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Cardiovascular Physiologist, Johns Hopkins University

This fundamental principle of cardiac physiology explains why athletes often exhibit mild left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)—a condition known as \"athlete’s heart.\" Their hearts adapt to sustained aerobic demands, increasing stroke volume and efficiency without pathology.

Pathological vs. Physiological Thickening

While a naturally thicker left ventricle is normal, abnormal thickening—known as left ventricular hypertrophy—can signal underlying disease. Chronic hypertension is the most common cause. When blood pressure remains elevated over time, the left ventricle must work harder with each beat, leading to progressive muscle thickening.

Other causes include aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and long-term intense weightlifting without cardiovascular balance. Unlike physiological hypertrophy, pathological LVH may reduce chamber volume, impair diastolic filling, and increase the risk of arrhythmias, heart failure, or sudden cardiac death.

Recognizing Risk Factors for Abnormal Thickening

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure

- Genetic predisposition to cardiomyopathy

- Obesity and insulin resistance

- Sedentary lifestyle or extreme endurance training without recovery

- Chronic sleep apnea

Mini Case Study: Early Detection Prevents Progression

James, a 52-year-old warehouse supervisor, had no overt symptoms but was found to have stage 2 hypertension during a routine check-up. An echocardiogram revealed mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. His physician explained that years of unmanaged stress and poor diet had forced his heart to pump against consistently high resistance.

With a regimen including ACE inhibitors, dietary sodium reduction, and moderate aerobic exercise (brisk walking 5 days/week), James reduced his blood pressure to 130/85 mmHg within six months. A follow-up echo showed regression of LVH. This case underscores how timely intervention can reverse early structural changes, preserving heart function.

Step-by-Step Guide to Supporting Healthy Ventricular Function

- Monitor Blood Pressure Regularly: Check at home weekly if you're at risk. Aim for readings below 120/80 mmHg.

- Adopt a Heart-Healthy Diet: Emphasize whole grains, leafy greens, lean proteins, and potassium-rich foods. Limit processed foods and added salt.

- Engage in Consistent Aerobic Exercise: 150 minutes per week of moderate activity strengthens the heart without excessive strain.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Excess body mass increases cardiac workload and blood volume.

- Manage Stress and Sleep: Chronic stress elevates cortisol and blood pressure. Prioritize 7–8 hours of quality sleep nightly.

- Schedule Annual Cardiac Screenings: Especially if there’s family history of heart disease or hypertension.

Checklist: Maintaining Optimal Left Ventricle Health

- ✅ Get blood pressure checked every 6 months (or more often if elevated)

- ✅ Eat less than 2,300 mg of sodium daily

- ✅ Perform aerobic exercise at least 30 minutes, 5 times a week

- ✅ Avoid tobacco and limit alcohol consumption

- ✅ Track any symptoms like fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest discomfort

- ✅ Attend annual physical exams with ECG or echocardiogram as recommended

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a thickened left ventricle return to normal?

Yes, in many cases. If caused by controllable factors like high blood pressure, appropriate treatment—including medication, diet, and exercise—can lead to regression of left ventricular mass over time. Studies show reductions of up to 10–15% in wall thickness within one to two years of effective management.

Is left ventricular thickness always a sign of heart disease?

No. A thicker left ventricle is normal anatomy. What matters is whether the thickening is excessive relative to body size and hemodynamic needs. Athletes often have larger, thicker hearts due to adaptive remodeling, which is benign when accompanied by normal diastolic function and absence of symptoms.

How is ventricular thickness measured?

Echocardiography is the gold standard. It uses ultrasound waves to visualize heart structure and measure wall thickness in real time. MRI and CT scans can also assess myocardial mass with high precision, though they are used less frequently for routine screening.

Conclusion: Respecting the Heart’s Design for Longevity

The left ventricle’s greater thickness is not arbitrary—it reflects the heart’s elegant response to the physical demands of sustaining life. By understanding this design, individuals can appreciate the importance of protecting their cardiovascular system from unnecessary strain. Just as an engine wears faster under constant overload, so too does the heart suffer when forced to pump against chronically elevated resistance.

Small, consistent choices—like reducing salt intake, staying active, and managing stress—pay dividends in maintaining optimal ventricular structure and function. The heart works tirelessly without complaint; honoring its design with informed care ensures it continues doing so for decades.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?