A low anion gap is a subtle but potentially significant finding in routine blood work. While often overlooked compared to more commonly discussed electrolyte imbalances, it can point to serious underlying medical conditions. The anion gap measures the difference between positively and negatively charged electrolytes in your blood—specifically sodium (Na⁺), chloride (Cl⁻), and bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻). When this calculation yields a value below the normal range (typically less than 3–6 mEq/L, depending on lab standards), it signals an imbalance that warrants further investigation.

Unlike high anion gap metabolic acidosis, which is frequently linked to kidney failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, or poisoning, a low anion gap doesn’t produce dramatic symptoms on its own. Instead, it acts as a clue—a biochemical red flag—that something systemic may be wrong. Understanding what drives a low anion gap, recognizing associated signs, and knowing when to act can make a meaningful difference in early diagnosis and treatment.

What Is the Anion Gap?

The anion gap is calculated using a simple formula:

Anion Gap = [Na⁺] – ([Cl⁻] + [HCO₃⁻])

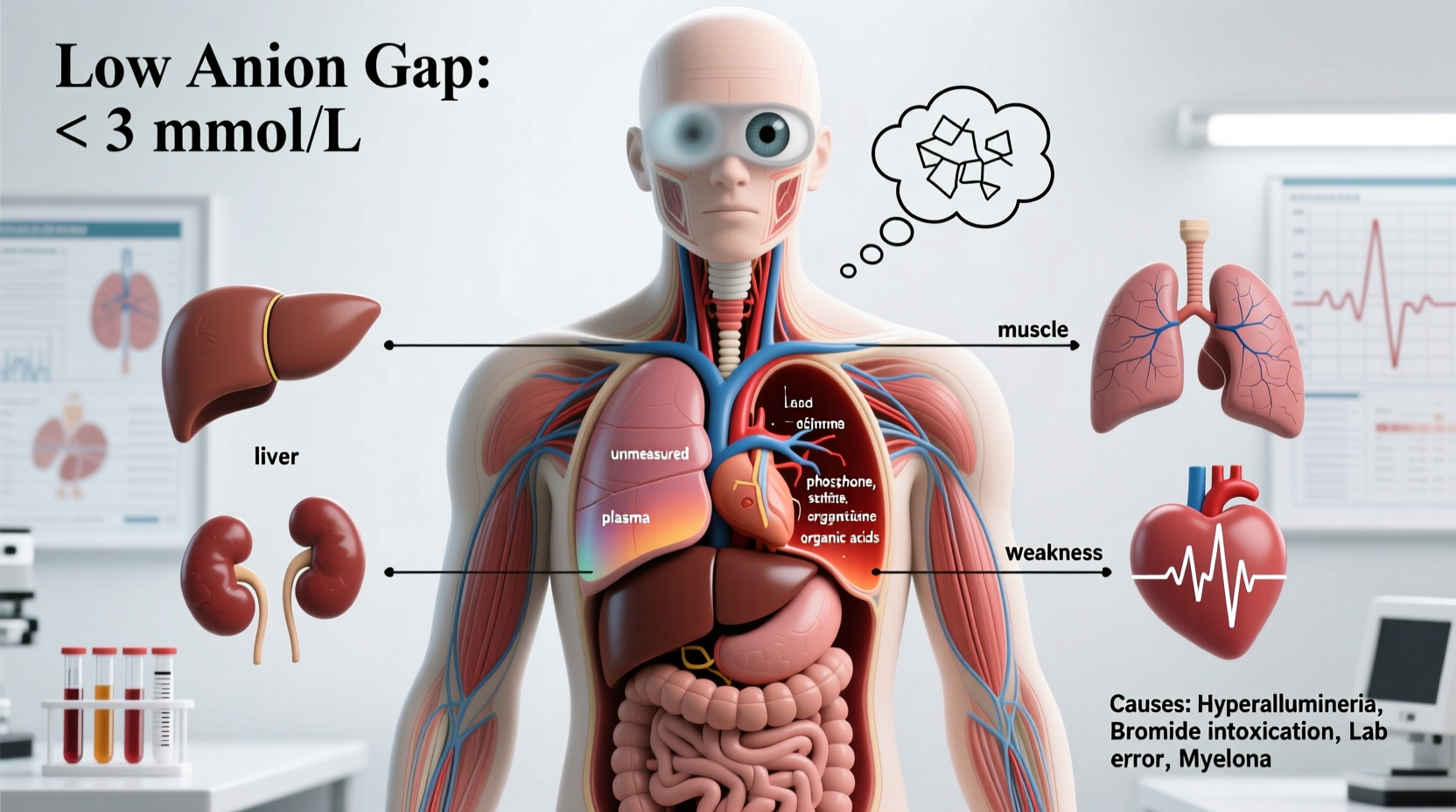

This equation reflects the balance of measured cations (positive ions) and anions (negative ions) in the bloodstream. Since not all ions are routinely measured, the \"gap\" represents unmeasured anions such as proteins, phosphates, sulfates, and organic acids. A normal anion gap typically ranges from 8 to 12 mEq/L, though reference values vary slightly by laboratory.

A low anion gap occurs when this value falls significantly below the expected range. This does not mean there are fewer ions overall—it suggests a shift in the relative concentrations of the major electrolytes, often due to changes in protein levels, paraproteins, or specific electrolyte abnormalities.

Common Causes of a Low Anion Gap

A persistently low anion gap is rarely due to random variation. It usually stems from one of several identifiable physiological or pathological mechanisms:

- Hypoalbuminemia: Albumin is a negatively charged protein and a major contributor to the anion gap. When albumin levels drop—common in liver disease, malnutrition, nephrotic syndrome, or chronic inflammation—the anion gap decreases proportionally. For every 1 g/dL decrease in serum albumin, the anion gap drops by approximately 2.5 mEq/L.

- Paraproteinemia: Conditions like multiple myeloma can produce large amounts of abnormal immunoglobulins, particularly IgG-type paraproteins, which carry a positive charge. These cationic proteins counteract unmeasured anions, effectively reducing the anion gap.

- Hyponatremia: Low sodium levels directly reduce the numerator in the anion gap equation, potentially lowering the result even if other electrolytes are stable.

- Bromide intoxication: Though rare, bromide (found in some older medications or contaminated water sources) can interfere with chloride assays, leading to pseudohyperchloremia and a falsely low anion gap.

- Lithium therapy: Chronic lithium use can displace other cations and alter electrolyte measurements, contributing to a reduced anion gap.

- Hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia: Elevated levels of these cations may indirectly affect the gap, especially in the presence of other electrolyte disturbances.

Symptoms and Clinical Signs

A low anion gap itself does not cause symptoms. However, the underlying conditions responsible for it often do. Symptoms depend entirely on the root cause:

- In **liver disease** or **malnutrition**, patients may experience fatigue, edema, jaundice, or muscle wasting.

- With **multiple myeloma**, bone pain, recurrent infections, anemia, and kidney dysfunction are common.

- Those with **nephrotic syndrome** often present with significant proteinuria, swelling in the legs, and frothy urine.

- Patients suffering from **bromide toxicity** may exhibit confusion, sedation, skin rashes, or neurological disturbances.

Because the anion gap is a calculated value rather than a direct symptom generator, clinicians must look beyond the number. A low gap should prompt evaluation of albumin, renal function, liver tests, and possibly serum protein electrophoresis—especially if no clear explanation exists.

“An abnormally low anion gap should never be dismissed as a lab error. In experienced hands, it can be the first clue to a hidden plasma cell disorder.” — Dr. Rajiv Mehta, Nephrologist and Electrolyte Specialist

Diagnostic Approach and Interpretation

Evaluating a low anion gap requires a systematic approach. Consider the following steps:

- Verify accuracy: Confirm the result with a repeat electrolyte panel. Labs can have technical errors, especially with older analyzers sensitive to paraproteins.

- Check albumin level: Correct the anion gap using the Figge-Jabor-Kazda-Fencl equation: Adjusted AG = Calculated AG + (0.25 × [Normal Albumin – Measured Albumin]).

- Assess for paraproteins: Order serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation if myeloma is suspected.

- Review medication history: Lithium, bromide-containing compounds, or iodine-based contrast agents can influence results.

- Look at overall acid-base status: Use arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis to rule out mixed acid-base disorders, even if the anion gap is low.

When to Suspect Multiple Myeloma

A strikingly low or negative anion gap in an older adult with unexplained bone pain, anemia, or kidney issues should raise suspicion for multiple myeloma. One study found that nearly 20% of myeloma patients had an anion gap ≤0 mEq/L, making it a useful screening clue.

Do’s and Don’ts in Managing Low Anion Gap Findings

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Correct the anion gap for albumin levels in critically ill or malnourished patients. | Ignore a low anion gap simply because the patient seems well. |

| Order SPEP and free light chains if myeloma risk factors are present. | Assume the result is a lab error without clinical correlation. |

| Monitor electrolytes regularly in patients on lithium or with chronic kidney disease. | Treat the number alone instead of investigating the underlying condition. |

| Consider toxicology screening in cases of unexplained neurologic symptoms and low gap. | Overlook nutritional status and protein intake in hospitalized patients. |

Mini Case Study: Uncovering Hidden Myeloma

Mr. Thompson, a 72-year-old man, was admitted for hip fracture repair. Preoperative labs showed a sodium of 138 mEq/L, chloride of 110 mEq/L, bicarbonate of 22 mEq/L—anion gap of just 6 mEq/L. His albumin was 2.8 g/dL (low), but after correction, the adjusted anion gap was -1.2, indicating a true reduction.

Given his fatigue and mild renal impairment, the team ordered SPEP. Results revealed a monoclonal IgG kappa spike. Further testing confirmed multiple myeloma. Early detection allowed prompt oncology referral and initiation of therapy before progression. The low anion gap, initially dismissed as incidental, turned out to be a critical diagnostic clue.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can dehydration cause a low anion gap?

No, dehydration typically concentrates electrolytes and may increase the anion gap or leave it unchanged. It’s more likely to mask underlying imbalances rather than cause a true low gap.

Is a low anion gap dangerous?

The gap itself isn’t harmful, but the conditions behind it—like myeloma, severe malnutrition, or toxin exposure—can be life-threatening if undiagnosed. The danger lies in missing the root cause.

How often should I get my anion gap checked?

Routine monitoring isn't necessary for healthy individuals. However, if you have chronic kidney disease, liver disease, or are undergoing chemotherapy, your doctor may track it during regular metabolic panels.

Action Plan: What to Do If Your Anion Gap Is Low

If your blood test reveals a low anion gap, follow this checklist to ensure proper follow-up:

- ✅ Confirm the result with a repeat basic metabolic panel.

- ✅ Check serum albumin and calculate the corrected anion gap.

- ✅ Evaluate for signs of malnutrition, liver disease, or kidney problems.

- ✅ Discuss your medication list with your provider—especially lithium or alternative remedies.

- ✅ Request further testing (SPEP, renal function, LFTs) if no obvious cause is found.

- ✅ Seek specialist input (nephrology, hematology) if myeloma or complex electrolyte issues are suspected.

Conclusion

A low anion gap is more than a laboratory curiosity—it’s a window into systemic health. While asymptomatic in itself, it often heralds conditions that demand attention: from nutritional deficiencies to hematologic cancers. Interpreting it correctly, adjusting for albumin, and pursuing appropriate diagnostics can uncover diseases in their early, most treatable stages.

Whether you’re a patient reviewing lab results or a clinician assessing a subtle abnormality, remember that small numbers can carry big meaning. Stay curious, ask questions, and advocate for thorough evaluation when something doesn’t add up—literally.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?