Greedy algorithms are among the most intuitive and efficient approaches in computer science for solving optimization problems. When applied correctly, they offer fast, elegant solutions that scale well. However, their simplicity can be deceptive—what appears to be a logical choice at each step may not always lead to a globally optimal result. Mastering greedy problems requires understanding when and how to apply this strategy effectively, recognizing patterns, and validating assumptions through proof techniques.

This guide walks through the core principles of greedy algorithms, outlines a structured problem-solving approach, and provides practical insights backed by real examples and expert reasoning.

Understanding the Greedy Approach

A greedy algorithm makes locally optimal choices at each stage with the hope of finding a global optimum. Unlike dynamic programming, which explores all possibilities, greedy methods commit early and never backtrack. This leads to faster execution but demands careful validation: not every problem supports a greedy solution.

The key characteristics of problems suitable for greedy strategies include:

- Optimal substructure: An optimal solution contains optimal solutions to subproblems.

- Greedy choice property: A globally optimal solution can be reached by making a locally optimal (greedy) choice.

Common domains where greedy algorithms shine include scheduling, coin change (for canonical systems), Huffman coding, minimum spanning trees (Kruskal’s and Prim’s), and activity selection.

“The art of the greedy method lies not in making quick decisions, but in proving that the fastest decision is also the best.” — Dr. Anita Rao, Algorithms Researcher at MIT

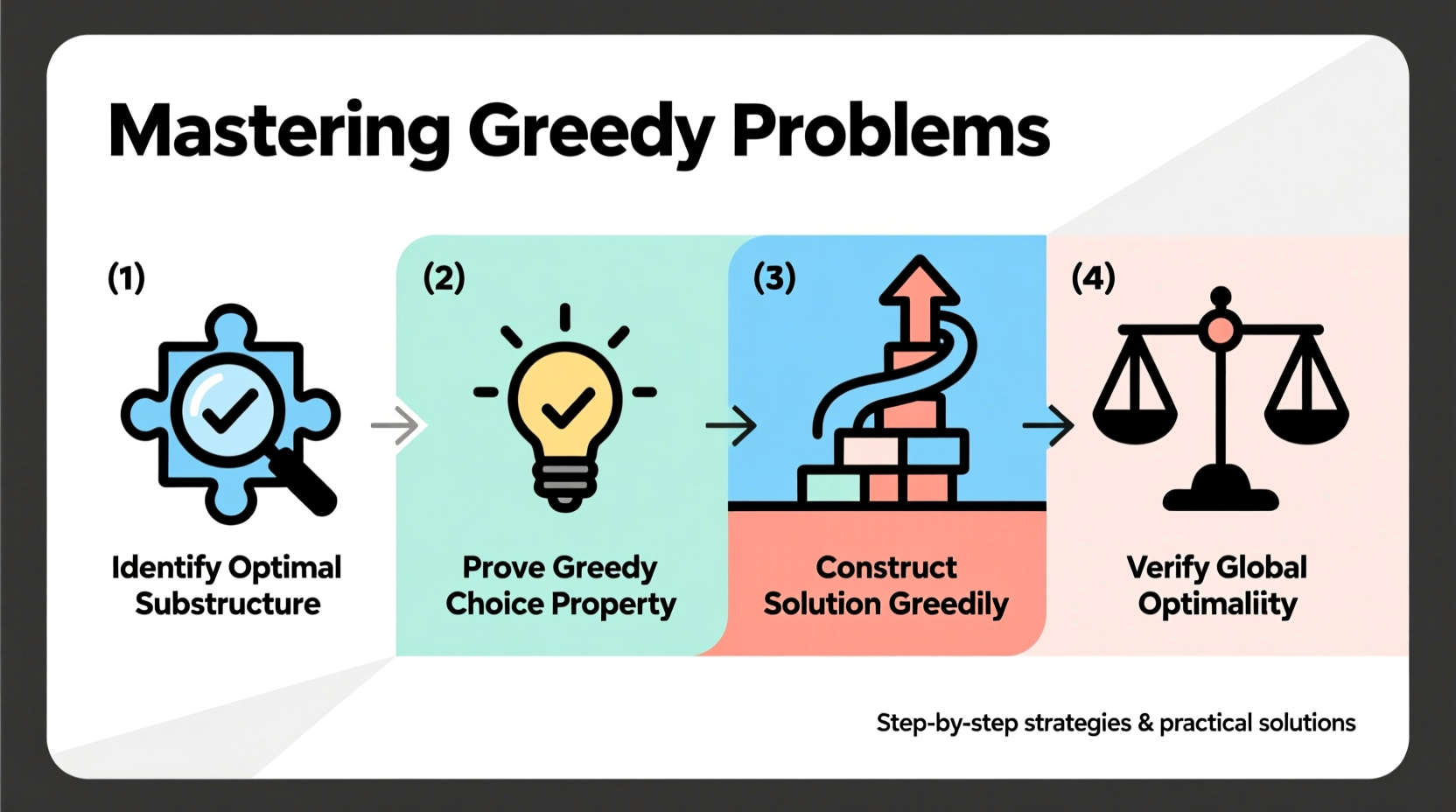

Step-by-Step Strategy to Solve Greedy Problems

Approaching greedy problems without a framework often leads to incorrect assumptions. Follow this five-step process to increase accuracy and confidence.

- Identify candidate elements: Determine what constitutes a \"choice\"—intervals, jobs, coins, etc.

- Define selection criteria: What rule will guide your greedy choice? Earliest finish time? Highest value per unit weight?

- Sort inputs accordingly: Arrange data based on the chosen criterion to enable sequential processing.

- Iterate and build solution: Make one choice at a time, updating state as needed.

- Validate optimality: Use exchange arguments or contradiction proofs to confirm correctness.

Real Example: Activity Selection Problem

Consider a list of activities, each with a start and finish time. The goal is to select the maximum number of non-overlapping activities.

Suppose you have these activities sorted by finish time:

| Activity | Start | Finish |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 1 | 3 |

| A2 | 3 | 5 |

| A3 | 0 | 6 |

| A4 | 5 | 7 |

| A5 | 8 | 9 |

The greedy strategy selects the activity with the earliest finish time first (A1). Then it picks the next compatible activity (A2), followed by A4 and A5. Total selected: 4.

If instead we had chosen A3 first (longest duration), only one activity could run. This illustrates why \"earliest finish time\" works—it frees up resources sooner, enabling more future selections.

When Greedy Fails—and How to Know

Not all optimization problems respect the greedy choice property. For example, the 0/1 Knapsack problem cannot be solved greedily because selecting the highest value-per-weight item first doesn’t guarantee an optimal total value when items can't be split.

In contrast, the fractional knapsack problem allows partial items, so a greedy approach based on value density yields the correct result.

To distinguish between valid and invalid applications:

- Attempt to construct a counterexample where the greedy path fails.

- Apply an exchange argument: assume an optimal solution exists that differs from yours, then show you can replace elements to match your solution without loss of optimality.

Practical Checklist for Implementing Greedy Solutions

Before writing code, ensure your approach meets the necessary conditions. Use this checklist to verify readiness:

- ✅ Is the problem about maximizing or minimizing a quantity under constraints?

- ✅ Can decisions be made sequentially without needing to revisit prior choices?

- ✅ Have I identified a plausible greedy criterion (e.g., earliest end, shortest duration, highest ratio)?

- ✅ Is the input sorted appropriately to support the greedy order?

- ✅ Can I formally argue—or at least strongly justify—that the greedy choice preserves optimality?

- ✅ Have I tested edge cases like overlapping intervals, equal weights, or single-element inputs?

Comparison Table: Greedy vs Dynamic Programming

Choosing between greedy and DP depends on structure and constraints. Here's a comparison to clarify trade-offs:

| Aspect | Greedy Algorithm | Dynamic Programming |

|---|---|---|

| Time Complexity | O(n log n) due to sorting | O(n²) or higher |

| Space Complexity | O(1) auxiliary | O(n) typically |

| Backtracking | No—decisions are final | Yes—explores multiple paths |

| Proof Requirement | Mandatory (exchange argument) | Inductive correctness sufficient |

| Best For | Canonical coin systems, interval scheduling | 0/1 Knapsack, Longest Common Subsequence |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a greedy algorithm ever give a wrong answer even if it seems logical?

Yes. Many problems appear amenable to greedy strategies but fail upon deeper inspection. For instance, using the largest coin first in arbitrary coin systems might miss the minimal count. Always validate with test cases and theoretical justification.

How do I come up with the right greedy criterion?

Look for patterns in optimal solutions. Try small instances manually and observe which choice consistently appears in the best outcome. Common heuristics include earliest completion, smallest size, highest benefit-to-cost ratio, or latest start.

Is sorting always required in greedy algorithms?

Not always, but very often. Since greedy choices depend on relative ordering (e.g., who finishes first), preprocessing via sorting enables efficient iteration. Exceptions exist—for example, Huffman coding uses a priority queue instead of pre-sorting.

Conclusion: From Intuition to Mastery

Mastering greedy problems isn’t just about memorizing patterns—it’s about cultivating disciplined thinking. Start by identifying the decision points in a problem, then rigorously evaluate whether a myopic choice leads to a wise outcome. With consistent practice and attention to proof techniques, you’ll develop the instinct to separate viable greedy solutions from tempting traps.

Whether you're preparing for technical interviews or optimizing real-world systems, the ability to design and defend greedy algorithms is a powerful asset. Apply these strategies deliberately, question assumptions, and refine your intuition through implementation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?