Understanding a company’s true liquidity position is essential for investors, analysts, and financial managers. While cash on hand provides immediate insight, it doesn’t tell the full story. That’s where cash equivalents come in—short-term, highly liquid assets that can be quickly converted into cash with minimal risk. Accurately calculating cash equivalents enhances financial clarity, supports better decision-making, and improves the reliability of liquidity ratios like the current ratio and quick ratio.

This guide breaks down the process of identifying, classifying, and calculating cash equivalents with precision. Whether you're analyzing balance sheets or preparing internal reports, mastering this skill ensures your financial assessments reflect real-world conditions.

What Are Cash Equivalents?

Cash equivalents are short-term investments that are both readily convertible to known amounts of cash and so near maturity that their value is unlikely to fluctuate significantly due to interest rate changes. Typically, these instruments have original maturities of three months or less from the date of purchase.

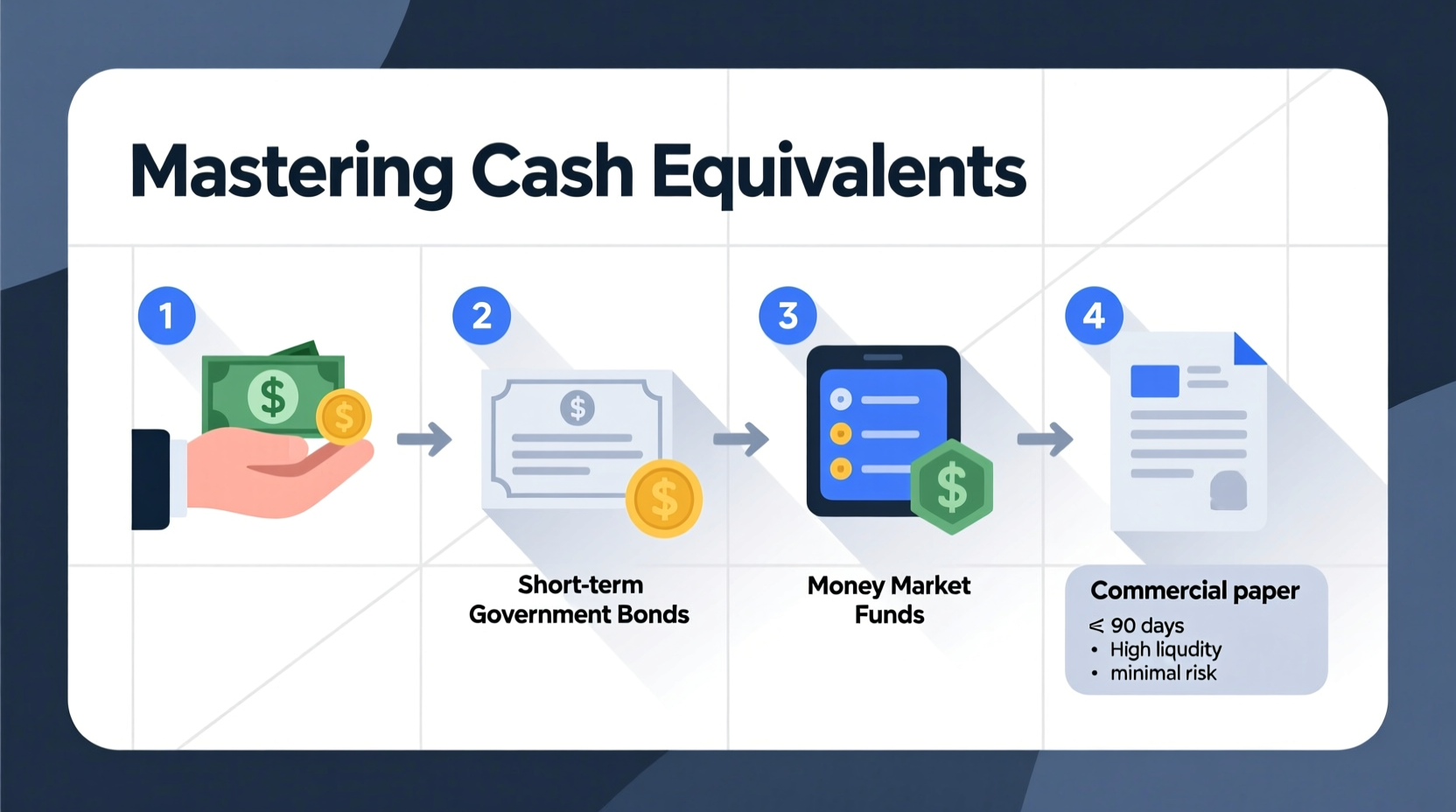

Common examples include:

- Treasury bills (T-bills)

- Commercial paper

- Money market funds

- Certificates of deposit (CDs) with maturities under 90 days

- Short-term government bonds

It's important to distinguish between cash and cash equivalents. Cash refers to physical currency, demand deposits, and checking accounts. Cash equivalents, while not cash per se, function similarly in terms of accessibility and stability.

“Cash equivalents provide a buffer between idle cash and long-term investments, offering liquidity without sacrificing safety.” — Dr. Linda Chen, Financial Analyst and Professor of Corporate Finance

Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Cash Equivalents

Accurate calculation begins with proper identification and classification. Follow these steps to ensure precision in your financial analysis.

- Review the Balance Sheet: Locate the “Cash and Cash Equivalents” line item under current assets. This figure often combines both elements, but detailed disclosures in footnotes may separate them.

- Identify Short-Term Investments: Examine the company’s investment portfolio. Look for securities with maturities of 90 days or less at time of purchase.

- Verify Liquidity and Risk Profile: Confirm that each asset meets the criteria: high credit quality, active secondary market, and minimal price volatility.

- Exclude Restricted Funds: Any cash or investment set aside for specific purposes (e.g., loan collateral or legal settlements) should not be included.

- Sum Eligible Assets: Add all qualifying instruments to determine total cash equivalents.

Real Example: Analyzing TechNova Inc.’s Balance Sheet

TechNova Inc. reports $5 million in cash and an additional $3 million in short-term investments. Upon reviewing the notes to the financial statements, the breakdown reveals:

- $1.2 million in 60-day Treasury bills

- $1.0 million in money market funds

- $700,000 in commercial paper (original maturity: 80 days)

- $300,000 in a 120-day CD

- $800,000 restricted for debt repayment

Of these, only the first three qualify as cash equivalents because they meet the 90-day maturity rule and are unrestricted. The 120-day CD exceeds the maturity threshold, and the $800,000 is restricted. Therefore, the correct cash equivalents amount is:

$1.2M + $1.0M + $0.7M = $2.9 million

The initially reported $3 million in short-term investments overstates liquid holdings by $1.1 million when misclassified items are excluded.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Misclassifying assets as cash equivalents can distort liquidity metrics and lead to flawed conclusions. Below is a comparison of common mistakes and best practices.

| Pitfall | Why It’s Wrong | Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Including 6-month CDs | Maturity exceeds 90 days; subject to interest rate risk | Only include instruments with original maturities ≤ 90 days |

| Counting equity investments | Stocks and mutual funds lack price stability and guaranteed conversion | Stick to debt instruments with low volatility |

| Ignoring restrictions | Funds legally held back aren't available for operations | Review disclosures for encumbrances or usage limitations |

| Using market value instead of cost | Cash equivalents are recorded at amortized cost | Use acquisition cost adjusted for minor accruals |

Key Applications in Financial Analysis

Once correctly calculated, cash equivalents play a critical role in evaluating a company’s financial health. Here’s how they’re used:

- Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio): (Cash + Cash Equivalents + Accounts Receivable) / Current Liabilities. Excludes inventory, providing a stricter measure of liquidity.

- Cash Conversion Cycle: Helps assess how quickly a company turns investments into cash flow from operations.

- Burn Rate Analysis: For startups, dividing monthly operating losses by cash and cash equivalents gives runway duration.

- Debt Coverage Assessment: Lenders examine cash equivalents to gauge ability to service short-term obligations.

Checklist: Validating Cash Equivalents

- ✅ Maturity at purchase was 90 days or less

- ✅ Issuer has high credit rating (e.g., A-1/P-1 or equivalent)

- ✅ Instrument is actively traded or redeemable on demand

- ✅ Not pledged as collateral or otherwise restricted

- ✅ Valued at amortized cost, not market price

- ✅ Disclosed appropriately in financial statement footnotes

Frequently Asked Questions

Can mutual funds be considered cash equivalents?

Generally, no. Most mutual funds do not qualify because their net asset value fluctuates daily and redemption may take more than one business day. However, certain money market mutual funds that invest solely in short-term, high-grade debt may be acceptable if they meet strict liquidity and maturity criteria.

Are foreign currency holdings included in cash equivalents?

Yes, provided they are in stable currencies and held in easily accessible accounts. However, exchange rate fluctuations introduce some risk, so analysts often note significant foreign holdings separately. Translation into reporting currency follows accounting standards (e.g., IFRS or GAAP).

How often should cash equivalents be re-evaluated?

At every reporting period—quarterly for public companies, monthly for internal management reviews. Instruments must be reassessed based on their original maturity, not remaining time. A bond purchased with a 100-day term never qualifies, even if only 20 days remain.

Conclusion: Strengthen Your Financial Insight

Mastering the calculation of cash equivalents sharpens your ability to assess liquidity with accuracy and confidence. It transforms vague assumptions into data-driven insights, enabling smarter investment choices, stronger financial planning, and more credible reporting. By applying rigorous classification standards and avoiding common errors, you ensure that your analysis reflects not just numbers—but reality.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?