Accuracy in measurement and calculation is not just about getting the right answer—it's about communicating how precise that answer truly is. Significant numbers, or significant figures, are the cornerstone of scientific precision. They reflect the reliability of measured data and ensure consistency across disciplines like chemistry, physics, engineering, and even finance. Misunderstanding or misapplying them can lead to misleading results, flawed conclusions, and errors in real-world applications such as pharmaceutical dosing or structural design.

This guide breaks down the rules of significant figures with clarity and practicality, offering actionable steps, real examples, and expert insights to help you master their use in everyday calculations.

Understanding What Makes a Digit Significant

Not all digits in a number carry equal weight. Significant figures include all certain digits plus one estimated digit in a measurement. The goal is to represent only the precision your tools allow.

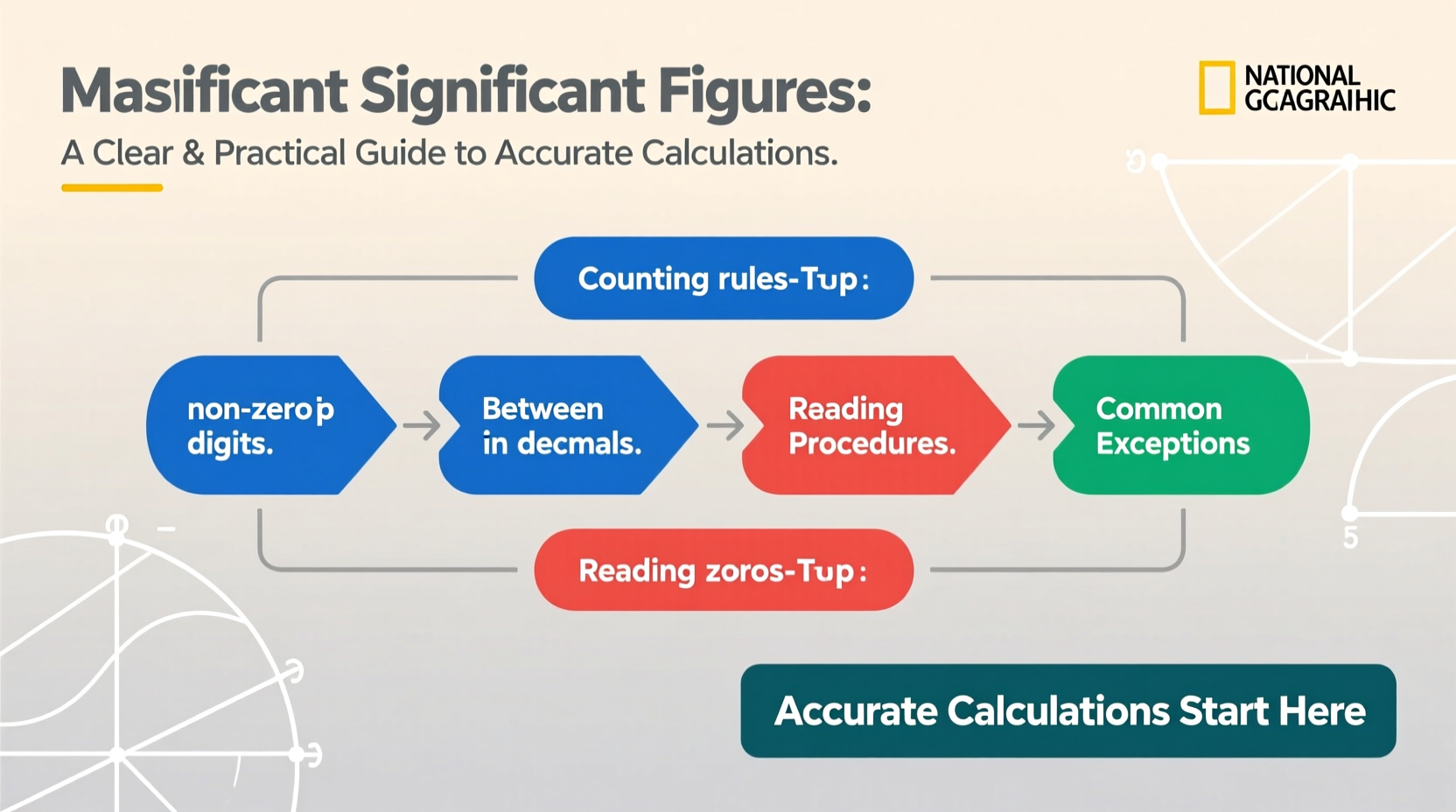

The following rules determine which digits are significant:

- Non-zero digits are always significant. For example, 345 has three significant figures.

- Zeros between non-zero digits are significant. In 1007, all four digits are significant.

- Leading zeros are never significant. In 0.0045, only the 4 and 5 count—two significant figures.

- Trailing zeros after a decimal point are significant. So 6.400 has four significant figures.

- Trailing zeros in a whole number without a decimal may or may not be significant. For instance, 2000 could have one, two, three, or four significant figures depending on context. Scientific notation removes ambiguity: 2.00 × 10³ clearly has three.

Applying Rules in Arithmetic: Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication, and Division

Once you identify significant figures in individual values, applying them correctly during calculations is crucial. The rules differ based on operation type.

Addition and Subtraction

For addition and subtraction, the result should be rounded to the least precise decimal place—not the number of significant figures.

Example: 12.345 (to the thousandth) + 6.2 (to the tenth) = 18.545 → rounded to **18.5**

Multiplication and Division

Here, the result must have the same number of significant figures as the value with the fewest.

Example: 5.67 (3 sig figs) × 2.3 (2 sig figs) = 13.041 → rounded to **13** (2 sig figs)

“Significant figures aren’t arbitrary—they’re a language of uncertainty. Ignoring them is like quoting a distance down to the millimeter when using a ruler marked only in meters.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Physics Educator and Lab Coordinator

Step-by-Step Guide to Handling Significant Figures in Calculations

Follow this sequence to maintain accuracy from start to finish:

- Identify significant figures in each number. Apply the five core rules carefully.

- Determine the type of operation. Is it addition/subtraction or multiplication/division? This dictates rounding rules.

- Perform the calculation with full precision. Use your calculator’s full output initially.

- Apply rounding rules based on operation type. Don’t round intermediate steps too early.

- Express the final answer with correct significant figures and units.

- Double-check ambiguous zeros using scientific notation if needed.

Mini Case Study: Measuring Reactant Mass in a Chemistry Lab

A student measures two chemicals: 4.56 g (three sig figs) and 1.2 g (two sig figs). They add them for a reaction. The total mass is 5.76 g, but since 1.2 is only precise to the tenths place, the sum must be reported as **5.8 g**—rounded to the nearest tenth. Reporting 5.76 g would falsely imply precision beyond the measuring tool’s capability. This attention to detail ensures replicability and safety in experimental settings.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced students and professionals make mistakes with significant figures. Below is a comparison of frequent errors and their corrections.

| Common Mistake | Correct Approach |

|---|---|

| Treating all zeros the same way | Differentiate leading, captive, and trailing zeros using the five rules |

| Rounding too early in multi-step calculations | Keep extra digits during intermediate steps; round only the final answer |

| Using addition rules for multiplication problems | Match the operation to the correct sig fig rule set |

| Assuming counted numbers have limited precision | Exact counts (e.g., 3 trials) are considered infinitely precise—no sig fig limit |

| Reporting more digits than justified by instruments | Align final answer with the least precise input measurement |

Checklist: Mastering Significant Numbers in 6 Steps

Use this checklist whenever performing measurements or calculations requiring precision:

- ✅ Identify all significant digits in given values using standard rules

- ✅ Distinguish between measured values and exact counts (e.g., conversion factors)

- ✅ Perform arithmetic without premature rounding

- ✅ Apply correct sig fig rules based on operation type

- ✅ Express final answer with appropriate units and significant figures

- ✅ Verify results using scientific notation if zeros cause ambiguity

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are significant figures important in science?

They communicate the precision of measurements. Without them, a number like “100” could mean anything from 95 to 105—or exactly 100.00. Sig figs prevent overstatement of accuracy and ensure transparency in data reporting.

Do exact numbers affect significant figures in calculations?

No. Exact numbers—such as counted items (6 molecules) or defined constants (1 km = 1000 m)—have infinite significant figures and do not limit the precision of the result.

How many significant figures does 0.002050 have?

It has four. Leading zeros are not significant. The first non-zero digit is 2, followed by 0, 5, and a trailing zero after the decimal, which is significant. So: 2, 0, 5, 0 → four significant figures.

Conclusion: Precision Is a Skill Worth Perfecting

Mastering how to do significant numbers isn’t about memorizing rules—it’s about developing a mindset of precision and honesty in data. Whether you're balancing chemical equations, analyzing financial models, or designing mechanical systems, the way you report numbers shapes how others interpret your work. Errors in sig fig application might seem minor, but compounded over complex processes, they can distort outcomes and erode trust.

By internalizing these principles and practicing them consistently, you build credibility and rigor into every calculation. Accuracy isn’t just about being correct—it’s about being transparently, reliably correct.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?