In mechanics, the concept of \"moment\" is foundational to understanding how forces influence rotational motion. Whether you're analyzing a seesaw at a playground or designing a bridge capable of bearing immense loads, the principles of moments govern stability and balance. Despite its importance, many students and enthusiasts struggle with identifying, calculating, and applying moments correctly. This guide demystifies the process, offering a structured approach to mastering moments through definitions, real-world context, calculation techniques, and practical problem-solving strategies.

What Is a Moment in Physics?

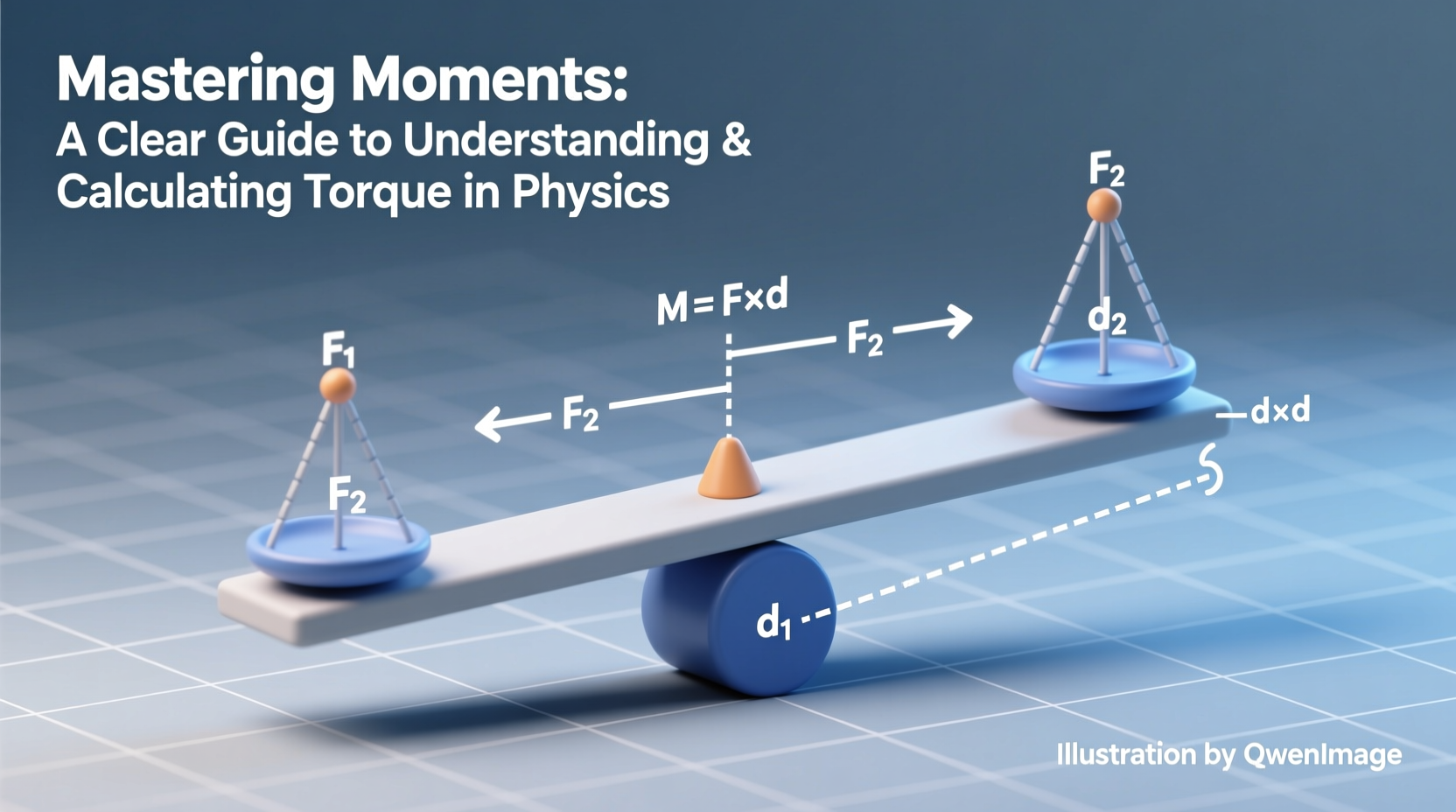

In physics, a moment—often referred to as torque when discussing rotation—is the measure of a force’s tendency to cause a body to rotate about a specific point or axis. It is not the force itself but rather the rotational effect that force produces. The moment depends on two key factors: the magnitude of the applied force and the perpendicular distance from the point of rotation (pivot) to the line of action of the force.

The standard formula for calculating a moment is:

Moment = Force × Perpendicular Distance

Or mathematically: M = F × d⊥

The unit of moment is the newton-meter (N·m), though it should not be confused with the joule (J), which measures energy. Moments are vector quantities, possessing both magnitude and direction—clockwise or counterclockwise—which plays a critical role in determining rotational equilibrium.

Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Moments

Finding the moment of a force involves more than plugging numbers into a formula. A systematic approach ensures accuracy and builds confidence in problem-solving. Follow these steps to calculate moments effectively:

- Identify the pivot point: Determine the fixed point or axis around which rotation occurs. This is often called the fulcrum.

- Locate all applied forces: List every force acting on the object, including weight, tension, normal force, and external pushes or pulls.

- Determine the perpendicular distance: For each force, measure the shortest distance from the pivot to the line along which the force acts. If the force is not perpendicular, use trigonometry to resolve components.

- Calculate individual moments: Multiply each force by its corresponding perpendicular distance. Assign a direction: clockwise (negative) or counterclockwise (positive), depending on convention.

- Sum the moments: Add all moments algebraically. If the net moment is zero, the system is in rotational equilibrium.

This method applies universally, whether analyzing a simple lever or a complex truss structure.

Real-World Application: The Seesaw Problem

Consider a classic example: two children sitting on a seesaw balanced over a central pivot. Child A weighs 300 N and sits 2 meters to the left of the pivot. Child B weighs 400 N. Where must Child B sit for the seesaw to remain level?

For equilibrium, the sum of clockwise moments must equal the sum of counterclockwise moments.

- Moment due to Child A (counterclockwise): 300 N × 2 m = 600 N·m

- Moment due to Child B (clockwise): 400 N × d = ?

To balance: 400 × d = 600 → d = 600 / 400 = 1.5 meters

Child B must sit 1.5 meters to the right of the pivot. This scenario illustrates the principle of moments in everyday life—equalizing turning effects to maintain stability.

“Understanding moments isn’t just academic—it’s what keeps cranes from tipping and buildings from collapsing.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Structural Engineer

Resolving Non-Perpendicular Forces

Many problems involve forces applied at an angle, requiring resolution into components. When a force acts at an angle θ to the horizontal, only the component perpendicular to the lever arm contributes to the moment.

The effective force becomes: F⊥ = F × sin(θ)

Therefore, the moment is: M = F × sin(θ) × d

For example, pushing a wrench at a 30° angle reduces its effectiveness by half because sin(30°) = 0.5. Applying 100 N at this angle yields only 50 N of useful rotational force.

| Angle (θ) | sin(θ) | Effective Force (%) | Moment Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0° | 0.0 | 0% | No rotation |

| 30° | 0.5 | 50% | Reduced efficiency |

| 60° | 0.87 | 87% | Near-optimal |

| 90° | 1.0 | 100% | Maximum moment |

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced learners make avoidable errors when calculating moments. Recognizing these pitfalls improves accuracy and deepens conceptual understanding.

- Using the wrong distance: Measuring along the lever instead of perpendicularly to the force line.

- Ignoring direction: Failing to assign clockwise or counterclockwise signs leads to incorrect net moment calculations.

- Overlooking all forces: Forgetting support reactions or the object’s own weight can unbalance the analysis.

- Misapplying trigonometry: Using cosine instead of sine when resolving angular forces.

A well-labeled diagram is essential. Sketch the object, mark the pivot, draw all forces with arrows, and indicate distances clearly. This visual aid prevents oversights and streamlines problem-solving.

Checklist for Solving Moment Problems

Use this checklist before finalizing any moment calculation:

- ✅ Identified the correct pivot point

- ✅ Listed all forces acting on the system

- ✅ Resolved angled forces into perpendicular components

- ✅ Measured distances perpendicularly from pivot to force lines

- ✅ Assigned correct signs (clockwise/counterclockwise)

- ✅ Summed moments and verified equilibrium (if applicable)

- ✅ Double-checked units and arithmetic

Advanced Insight: Moments in Engineering and Design

Beyond textbooks, moments play a vital role in engineering disciplines. In civil engineering, beams are analyzed under load to prevent excessive bending. Mechanical engineers design gear systems where torque transmission must be precise. Even in biomechanics, moments help analyze joint stresses during movement.

Take the example of a cantilever bridge: one end is anchored while the other extends freely. The weight of the bridge and traffic creates a moment around the anchor point. Engineers must ensure materials and supports can resist this rotational stress to prevent structural failure.

The principle also appears in sports. A golfer swinging a club generates torque around their shoulders. Longer clubs increase moment arm, potentially increasing speed—but also requiring greater control.

FAQ

Is moment the same as torque?

Yes, in physics and engineering, “moment” and “torque” are often used interchangeably when referring to rotational force. However, “moment” can also describe other rotational effects (e.g., bending moment), while “torque” specifically refers to twisting actions causing rotation.

Can a force have zero moment?

Yes. If a force is applied directly through the pivot point, the perpendicular distance is zero, so the moment is zero—even if the force is large. Such a force may cause translation but not rotation.

How do I know if a system is in rotational equilibrium?

A system is in rotational equilibrium when the sum of all clockwise moments equals the sum of all counterclockwise moments. In equation form: ΣM = 0. This condition is essential for stability in static structures.

Conclusion

Mastering how to find moment is more than a physics requirement—it’s a gateway to understanding how forces shape our physical world. From balancing a ruler on your finger to constructing skyscrapers, the principles remain consistent. With clear definitions, accurate diagrams, and disciplined calculation methods, anyone can develop proficiency in moments. Apply these concepts consistently, learn from mistakes, and test your understanding with real-life scenarios. The ability to predict and control rotational effects is not just academic; it’s a practical skill with lasting value.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?