Accurate auscultation of the lungs is a cornerstone of clinical assessment. Whether you're a medical student, nurse, or seasoned clinician, the ability to interpret breath sounds can reveal critical information about a patient’s respiratory status. Unlike imaging or lab tests, lung auscultation is immediate, non-invasive, and requires only a stethoscope—yet it remains underutilized due to inconsistent technique and misinterpretation. This guide breaks down the essentials of listening to the lungs, from positioning and equipment to recognizing normal and abnormal breath sounds with precision.

The Fundamentals of Lung Auscultation

Lung auscultation involves placing a stethoscope on specific areas of the chest to evaluate airflow through the bronchial tree. The goal is to detect changes in sound that may indicate obstruction, inflammation, fluid accumulation, or collapse. To begin, ensure the environment is quiet and the patient is seated upright, as this promotes full lung expansion. Expose the chest fully and warm the stethoscope diaphragm to avoid eliciting muscle tension.

Start by comparing left and right lung fields symmetrically. Move systematically: upper lobes (above the scapulae), mid-lung zones (between the scapulae), and lower lobes (below the scapulae). Listen during both inspiration and expiration, noting the quality, intensity, duration, and timing of each breath cycle.

Understanding Normal Breath Sounds

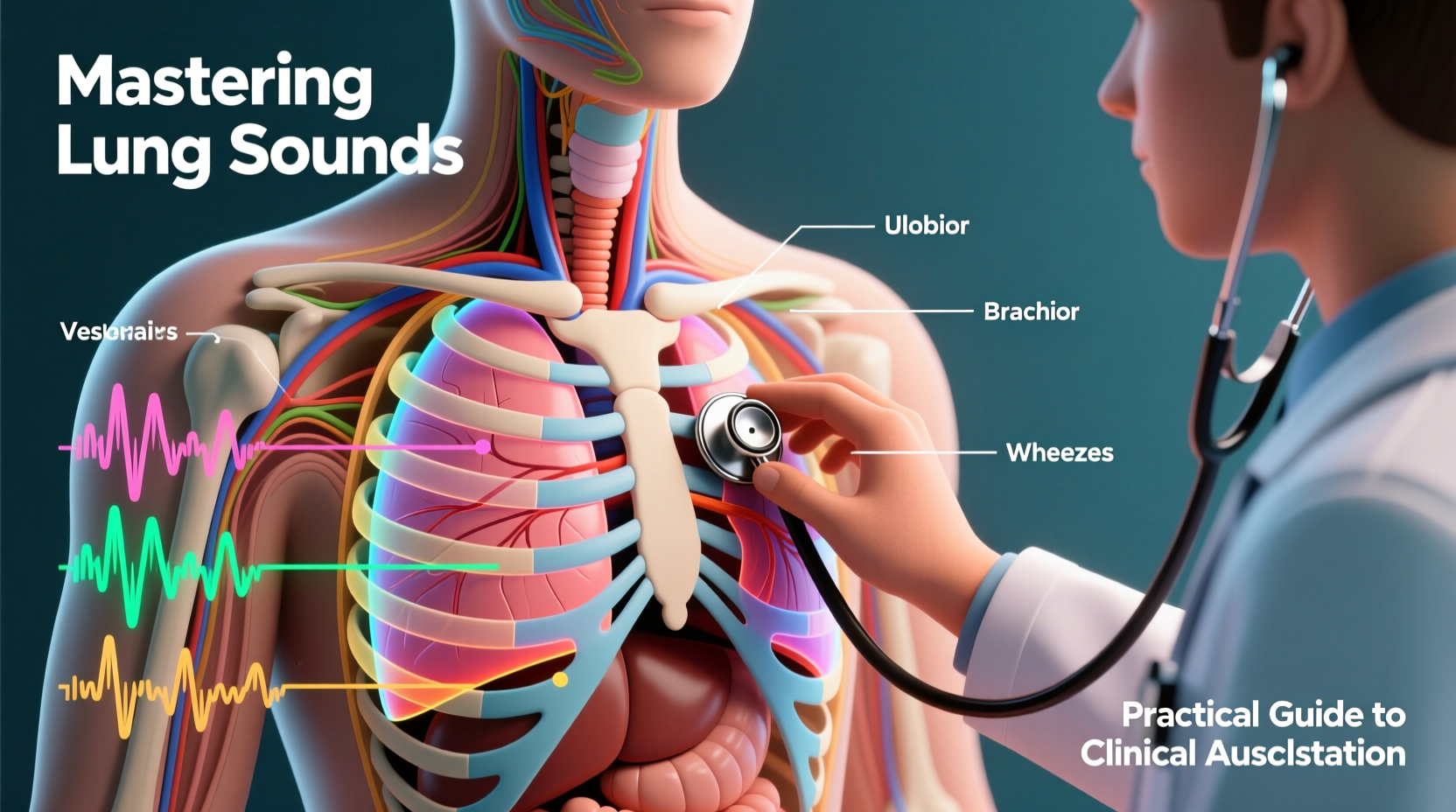

Normal breath sounds vary by location due to differences in airway size and tissue density. There are three primary types:

- Tracheal sounds: Loud, high-pitched, and heard over the trachea. Inspiration and expiration are roughly equal in duration.

- Bronchial sounds: Medium-pitched, heard over the sternum and upper anterior chest. Expiration is longer than inspiration.

- Vesicular sounds: Soft, low-pitched, and dominate most lung fields. Inspiration is significantly longer than expiration.

Vesicular sounds are the baseline for healthy peripheral lung tissue. Their presence throughout expected areas indicates unobstructed airflow. Absence or asymmetry should prompt further investigation.

“Listening is not passive—it’s an active diagnostic process. A subtle change in vesicular sound quality can precede radiographic findings by hours.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Pulmonologist and Clinical Educator

Identifying Abnormal Breath Sounds

Abnormal breath sounds provide vital clues to underlying pathology. Recognizing them early improves diagnostic accuracy and intervention speed.

Crackles (Rales)

Short, discontinuous popping sounds typically heard during late inspiration. Fine crackles suggest interstitial lung disease or early heart failure; coarse crackles point to bronchitis or pneumonia.

Wheezes

High-pitched, musical sounds occurring during expiration (or both phases) due to narrowed airways. Common in asthma, COPD, or bronchospasm. Monophonic wheezes may indicate localized obstruction.

Rhonchi

Low-pitched, snoring or gurgling sounds often cleared by coughing. Suggest mucus buildup in larger airways, common in bronchitis or atelectasis.

Stridor

A harsh, inspiratory sound originating from the upper airway. It signals possible obstruction—such as croup, foreign body, or vocal cord paralysis—and requires urgent evaluation.

Diminished or Absent Breath Sounds

Reduced or no audible sounds may indicate pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or severe consolidation. Always correlate with percussion and tactile fremitus.

Step-by-Step Guide to Effective Auscultation

Follow this structured approach to maximize diagnostic yield:

- Prepare the patient: Explain the procedure, ensure privacy, and position them upright with arms slightly forward to open intercostal spaces.

- Check your stethoscope: Ensure the earpieces are angled forward, the tubing is uncracked, and the diaphragm is secure.

- Begin posteriorly: Start at the apex of each lung (just above the shoulders), then move downward symmetrically.

- Compare sides: Listen at mirrored points on left and right. Note any asymmetry in volume or quality.

- Move to lateral and anterior fields: Include axillary regions and anterior chest, especially near the second intercostal space for potential cardiac-related lung signs.

- Assess voice transmission: Ask the patient to say “99” or “blue moon” while you auscultate. Increased transmission (bronchophony) suggests consolidation.

- Document findings: Record location, type, timing, and character of all sounds. Note whether they clear with coughing or change with position.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced clinicians make errors in lung auscultation. Awareness of these pitfalls improves consistency:

| Pitfall | Consequence | How to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Listening through clothing | Artifactual rustling sounds mask true breath sounds | Always expose skin directly |

| Insufficient patient cooperation | Shallow breathing obscures abnormalities | Instruct patient to breathe deeply through mouth |

| Skipping posterior bases | Miss early signs of effusion or atelectasis | Routinely include lower posterior fields |

| Confusing rhonchi with crackles | Incorrect diagnosis and treatment | Listen for response to cough: rhonchi often clear |

| Ignoring symmetry | Overlook unilateral disease | Compare side-to-side systematically |

Real-World Example: Detecting Early Heart Failure

During a routine check-up, a 68-year-old male with hypertension presented with mild fatigue. On physical exam, vital signs were stable, and lung sounds were clear anteriorly. However, upon posterior auscultation, fine crackles were detected bilaterally at the lung bases—only during late inspiration and not present when he first sat down, but reappeared after 30 seconds of sitting still.

This finding prompted measurement of BNP levels and an echocardiogram, which revealed reduced ejection fraction consistent with early systolic heart failure. The crackles represented pulmonary venous congestion before overt symptoms like dyspnea developed. Timely intervention with medication adjustment prevented hospitalization.

This case illustrates how meticulous auscultation—even in asymptomatic patients—can uncover hidden pathology.

Essential Checklist for Every Assessment

Use this checklist to ensure thoroughness during every lung exam:

- ✅ Patient seated upright, chest exposed

- ✅ Stethoscope warmed and functioning properly

- ✅ Auscultation performed posteriorly, laterally, and anteriorly

- ✅ Side-to-side comparison completed

- ✅ Deep mouth breathing encouraged

- ✅ All phases of respiration evaluated (inspiration/expiration)

- ✅ Voice sounds assessed if abnormality suspected

- ✅ Findings documented clearly and objectively

Frequently Asked Questions

Can breath sounds alone diagnose pneumonia?

No single finding is definitive, but crackles, bronchophony, and egophony together increase the likelihood of pneumonia. These should be correlated with fever, leukocytosis, and imaging when indicated.

Why do I sometimes hear sounds that disappear after the patient coughs?

Transient rhonchi or gurgling noises that clear with coughing are typically due to secretions in large airways. This is common in bronchitis and doesn’t necessarily indicate serious disease unless persistent.

Is it normal to hear slight wheezing in elderly patients at rest?

No. Wheezing at rest is never normal and suggests airflow limitation. Even mild chronic wheezing warrants evaluation for asthma, COPD, or other obstructive conditions.

Conclusion: Listening with Purpose

Mastering lung auscultation isn’t about memorizing sounds—it’s about developing the discipline to listen carefully, think critically, and act decisively. In an age of advanced diagnostics, the stethoscope remains a powerful tool when used skillfully. Each breath tells a story: of health, imbalance, or impending crisis. By refining your technique and staying vigilant, you transform simple listening into life-saving insight.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?